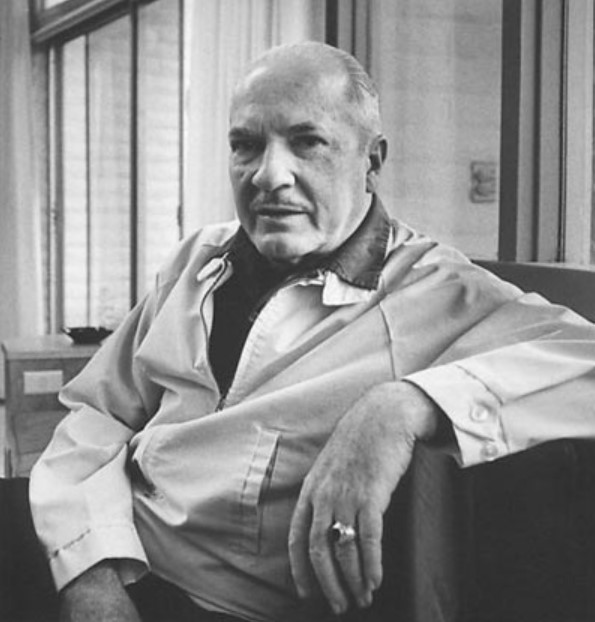

Robert A. Heinlein

The 'Dean of Science Fiction', according to the covers of all his books, Heinlein (July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was indeed a major writer and influence on the field. Until fairly recently, I might not have described him as a favourite writer, but having read a lot more Heinlein over the last two years, I'm coming round to the idea that he was great. The 'problem' with Heinlein, is that he divides opinion. He wrote books of quite different styles and with very different appeal, in different periods of his career, and he held very strong (and sometimes uncomfortable) ideas. Those challenges aside, however, he was highly intelligent, extremely inventive and wrote a lot of great SF.

Major Awards Won

Hugo Awards (12 nominations, 4 wins)

Double Star (1956)

Starship Troopers (1960)

Stranger in a Strange Land (1962)

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1967)

Nebula Awards (4 nominations, 0 wins)

SFWA Grand Master Award

(1975)

SF Bibliography (Novels)

Early Career - Including the entertaining 'Juveniles' written for Scribners

For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, 1939 (published posthumously, 2003)

Rocket Ship Galileo, 1947 - Juvenile

Beyond This Horizon, 1948

Space Cadet, 1948 - Juvenile

Red Planet, 1949 - Juvenile

Sixth Column, 1949

Farmer in the Sky, 1950 - Juvenile

Between Planets, 1951 - Juvenile

The Puppet Masters, 1951 - Excellent

The Rolling Stones, 1952 - Juvenile

- Excellent

Starman Jones, 1953 - Juvenile

The Star Beast, 1954 - Juvenile

Tunnel in the Sky, 1955 - Juvenile

Double Star, 1956 - Excellent

- Hugo Winner

Time for the Stars, 1956 - Juvenile

Citizen of the Galaxy, 1957 - Juvenile

The Door into Summer, 1957 - Excellent

Have Space Suit—Will Travel - Juvenile

Middle Career - Including much of Heinlein's better, more serious, adult fiction

Methuselah's Children, 1958

Starship Troopers, 1959 - Excellent(though it divides fans) - Hugo Winner

Stranger in a Strange Land, 1961 - Excellent

- Hugo Winner

Podkayne of Mars, 1963

Orphans of the Sky, 1963 - Very good

Glory Road, 1963

Farnham's Freehold, 1964 - Commonly disliked for controversial social commentary

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, 1966 - Excellent - Hugo Winner

I Will Fear No Evil, 1970 - Commonly considered to be one of his worst books

Time Enough for Love, 1973 - From here Heinlein really starts to focus on his hobby horses

Late career after 7 year haiatus recovering from poor health

The Number of the Beast, 1980 - Commonly considered a difficult book to like

The Pursuit of the Pankera, published 2020 - Alternate version of The Number of the Beast

Friday, 1982 - Very good

Job: A Comedy of Justice, 1984 - Very good

The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, 1985

To Sail Beyond the Sunset, 1987

Short Story Collections

The Man Who Sold the Moon, 1950

Waldo & Magic, Inc., 1950

The Green Hills of Earth, 1951

Assignment in Eternity, 1953

Revolt in 2100, 1953 ("If this goes on--", "Coventry", and "Misfit")

The Robert Heinlein Omnibus, 1958

The Menace From Earth, 1959

The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag, 1959 (a.k.a. 6 X H)

The Worlds of Robert A. Heinlein, 1966

The Past Through Tomorrow, 1967 - almost-complete Future History collection, see below

The Best of Robert A. Heinlein, 1973

Expanded Universe, 1980

Heinlein's Future History & World-As-Myth

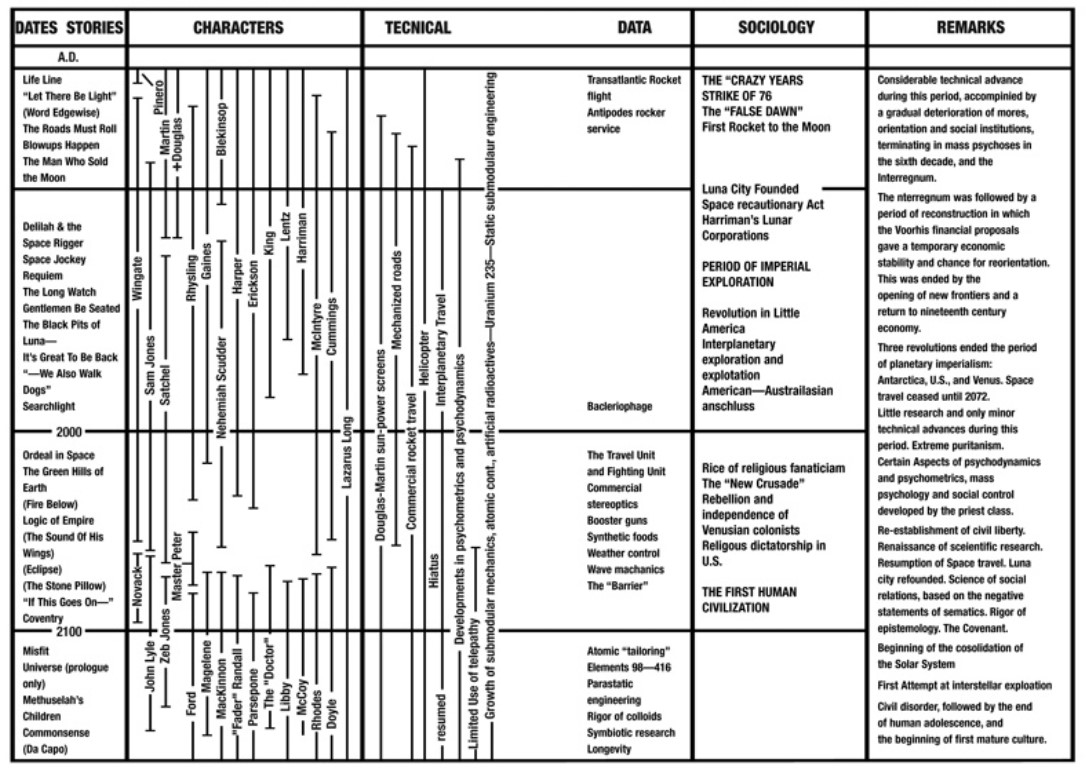

Like many SF writers, a good many of Heinlein's plots and characters are interconnected through multiple short stories and novels. However, almost uniquely, Heinlein planned this from the get-go, having discussed as early as 1941 how he would write an interconnected "Future History" for John W. Campbell's Astounding Science Fiction magazine. Campbell published a chart of these proposed stories in the May 1941 issue of the magazine, and Heinlein did indeed go on to write the majority of the stories described. Which is amazing really.

The chart shows Heinlein's plan for many of his short stories throughout the 1940's and 1950's. Almost all the stories from this era that are within the Future History sequence are collected in an excellent short story collection, The Past Through Tomorrow.

The Past Through Tomorrow

Life-Line (1939) – 20 pp short story. I enjoyed this, but it’s not essential for the timeline. More of interest as a very early Heinlein; first published in Astounding.

The Roads Must Roll (1940) – 38 pp novelette. This is a bit of a classic, and tells of a future union action that turns to violence. I’ve never been as fond of it as some anthologists, but it reads well. Heinlein on good form.

Blowups Happen (1940) – 48 pp novelette. This is strangely anachronistic, as very old stories can be if they take a stab at hard SF, as we now know atomic power doesn’t work quite the way Heinlein worried about, but it’s a well told story.

The Man Who Sold the Moon (1950) – 92 pp novella. Quote a long story, and a very good one. It’s many things: a good SF yarn, a study of a great but flawed genius, the use and misuse of money, greed and bullying, and the inevitability of ‘progress’.

Delilah and the Space-Rigger (1949) – 14 pp short story. This one is a bit, ‘meh’. It’s actually trying to rebut misogyny, but it’s so steeped in the sexism of the time, it hardly works these days. Not the best here.

Space Jockey (1947) – 18 pp short story. I had to look this up to try and remember it! Oh, yes it’s about a space pilot who ends up moving base to the moon. Kind of average, for Heinlein.

Requiem (1940) – 18 pp short story. This returns us to Harriman, the man who sold the moon, at the end of his life. It’s terrific; full of pathos and genuinely moving. Heinlein can really write.

The Long Watch (1949) – 14 pp short story. This is a nice story – and yet another where Heinlein is worrying about atomic power and atomic bombs. Nicely done and memorable.

Gentlemen, Be Seated (1948) – 10 pp short story. This is rather short, but it’s great! A moon disaster story.

The Black Pits of Luna (1948) – 14 pp short story. This is a juvenile, and it does read like one – the heroic protagonist is a young lad who needs to rescue his annoying sister. It’s okay, but not the best here.

"It's Great to Be Back!" (1947) – 18 pp short story. This is another classic that’s found in many anthologies. It is very good. The grass isn’t always greener, and appreciate what you have, etc.

"—We Also Walk Dogs" (1941) – 24 pp novelette. I really liked this, it works very well, and while the central SF idea (artificial gravity) is a bit silly, Heinlein casualty drops mobile phones into the plot – in 1941! The man was a genius.

Searchlight (1962) – 5 pp short story. Too short to be much. Okay; another moon rescue story.

Ordeal in Space (1948) – 27 pp short story. Okay; a man confronts his vertigo, gained in spce, with the aid of a cat. Quite nicely done. And I like stories with cats.

The Green Hills of Earth (1947) – 12 pp short story. A very well told story of the flawed man who authored the titular song. Art recreates the artist in its form, however accurate that may be.

Logic of Empire (1941) – 48 pp novella. Slavery and rebellion on Venus – which sounds odd these days, but Heinlein’s Future History is written in an old-school solar system. Rather good actually. I liked how the protagonist signed up for slavery when drunk!

The Menace from Earth (1957) – 26 pp novelette. This story is a strange one in a way – it’s nice enough, but almost seems like someone else wrote it. It’s not especially typical of Heinlein (it’s a bit of a romance). Not essential to the Future History plotting.

"If This Goes On —" (1940) – 136 pp novel. This really does read like a self-contained novel, albeit quite a short one. It's Heinlein imagining how the US might turn into a far right Christian dictatorship, and the rebellion against it. The characters are good, and it’s well told. I’m surprised it’s not been published more prominently other than in these collections.

Coventry (1940) – 48 pp novella. I really liked this story – one of my favourites from the collection about a man literally being sent to ‘Coventry’ for thinking independently, while not appreciating how good he’s got it in his modern world.

Misfit (1939) – 22pp novelette. This is a short little piece, written before most of the other stories, but set later. It tells of a misfit genius who helps move an asteroid to create a space station.

Methusalah’s Children (1958) – 175 pp novel. This novel caps the collection. I’ve not actually read it yet, so will comment on it in due course – I plan to read it shortly. It marks the first appearance of Lazarus Long, the protagonist of Time Enough for Love, which also links the Future History with Heinlein’s later World as Myth novels.

Connecting the Future History to World as Myth books and other novels

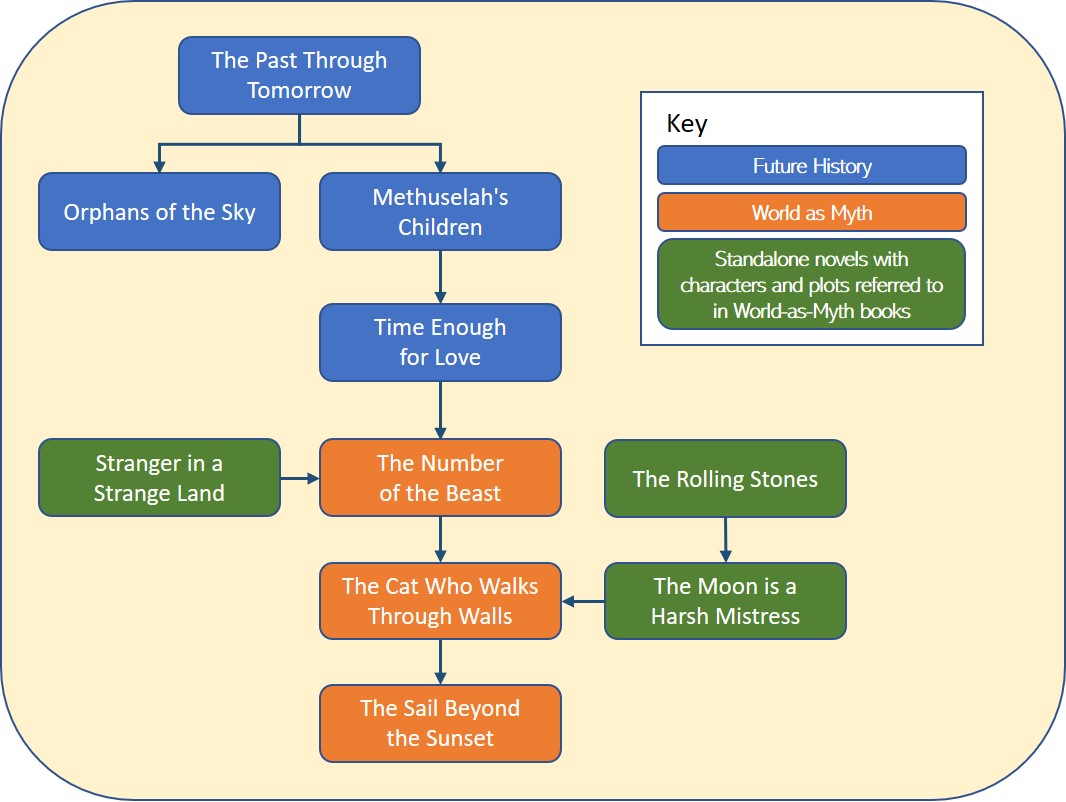

The Future History stories go on to link to Heinlein's World as Myth sequence principally through the character of Lazarus Long. How these stories all connect up, and the proposed reading order as shown in the graphic below.

It's perhaps unfortunate that multiple story strands meet at the point of The Number of the Beast, as this is a difficult and rather odd book in its structure and plot. An alternative version of the novel has very recently been released however, called The Pursuit of the Pankera, and this sounds easier to digest (I've not read it yet). However, I don't know how well it connects the various story threads, so I donlt explicitly include it in the graphic. If you want to skip The Number of the Beast, you can do that without the world imploding. The Cat Who Walks Through Walls and To Sail Beyond the Sunset are both commonly considered to be much easier (and better) reads. The connection of Cat... with The Rolling Stones and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, is the involvement of Hazel Stone (née Meade) in all these books (she also appears breifly in The Number of the Beast). There is no great need to read the standalone novels noted here in any order before you read the Future History and World-as-Myth books, but it may be enjoyable to know the characters. The Future history introduction of Lazarus Long, from Methusalah's Children onward is a good background to the World-as-Myth books, however, and probably is recommended if you are keen to follow the overall arc in the manner Heinlein presumably intended.