Clifford D. Simak

My personal top 10, recommended Simak novels:

City (1952)

Ring Around the Sun (1953)

Time is the Simplest Thing (1961)

Way Station (1963)

All Flesh Is Grass (1965)

Why Call Them Back From Heaven? (1967)

Out of Their Minds (1970)

Destiny Doll (1971)

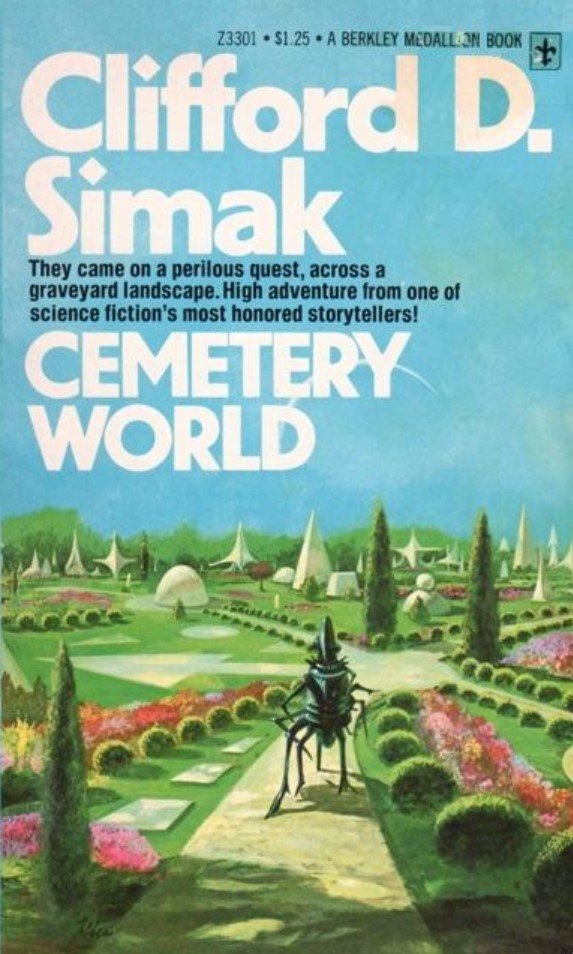

Cemetery World (1973)

Shakespeare's Planet (1976)

Clifford D. Simak (August 3, 1904 – April 25, 1988) was honored by fans with three Hugo Awards and by colleagues with one Nebula Award. The Science Fiction Writers of America made him its third SFWA Grand Master.

Simak was perhaps best known for writing 'pastoral' SF, in which benevolent aliens might land in rural Wisconsin to aid a local farmer in some small fashion.

Hugo Awards:

Grotto of the Dancing Deer (1981 short story winner)

Way Station (1964 novel winner)

The Big Front Yard (1959 novelette winner)

Nebula Award:

The Big Front Yard (1959 novelette winner)

Links for more information:

The excellent International Clifford D. Simak bibliography can be found here: http://www.simak-bibliography.com/

Bibliography

As noted, above, a superb, complete, international bibliography site exists for Clifford Simak. This is a cut-down version that list his novels and main story collections.

Novels

Cosmic Engineers (serialised 1939, expanded slightly for novel 1950)

Time and Again (1950)

Empire (1951)

City (1952) - excellent fix-up novel of stories originally appearing in Astounding between 1944-47

Ring Around the Sun (1952) - very good early novel

Time is the Simplest Thing (1961) - excellent

They Walked Like Men (1962) - alien invasion, with some great horror imagery

Way Station (1963) - perhaps his masterpiece; great novel

All Flesh Is Grass (1965) - excellent - presages Stephen King's The Dome

Why Call Them Back From Heaven? (1967) - a very impressive SF novel - one of his best

The Werewolf Principle (1967) - okay, but not my favourite

The Goblin Reservation (1968) - a middling quality science-fantasy

Out of Their Minds (1970)

Destiny Doll (1971) - a very impressive science-fantasy with much to recommend it

A Choice of Gods (1972)

Cemetery World (1973) - fun, and entertaining ideas, albeit a little uneven

Our Children's Children (1974) - good, and entertaining, but not quintessential Simak

Enchanted Pilgrimage (1975)

Shakespeare's Planet (1976) - a fast-paced romp to another world - entertainingly brisk

A Heritage of Stars (1977)

The Fellowship of the Talisman (1978)

Mastodonia (1978) (published as Catface in the UK)

The Visitors (1980)

Project Pope (1981)

Where the Evil Dwells (1982)

Special Deliverance (1982)

Highway of Eternity (1986)

Short Story Collections (printed books)

Strangers in the Universe (1956)

The Worlds of Clifford Simak (1960)

Aliens for Neighbours (1961) UK abridgment of The Worlds of Clifford Simak.

All the Traps of Earth and Other Stories (1962)

The Night of the Puudly (1964)

Worlds Without End (1964)

Best Science Fiction Stories of Clifford D. Simak (1967)

So Bright the Vision (1968)

The Best of Clifford D. Simak (1975)

Skirmish: The Great Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak (1977)

Brother And Other Stories (1986) - edited by Francis Lyall

The Marathon Photograph (1986) - edited by Francis Lyall

Off-Planet (1989) - edited by Francis Lyall

The Autumn Land and Other Stories (1990) - very good collection, edited by Francis Lyall

Immigrant and Other Stories (1991) - very good collection, edited by Francis Lyall

The Creator and Other Stories (1993)

Over the River and Through the Woods: The Best Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak (1996)

The Civilization Game and Other Stories (1997)

I Am Crying All Inside and Other Stories (The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak Volume One) (2015)

The Big Front Yard and Other Stories (The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak Volume Two) (2015)

The Ghost of a Model T and Other Stories (The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak Volume Three) (2015)

Clifford D. Simak Book Reviews

Cemetery World - Novel, 1973

Cemetery World is written with Simak's particular style and it was a pleasant way of reintroducing one to the author. It typically shows off Simak's clear prose and rather spare dialogue. It's certainly a refreshing style and overall I very much enjoyed reading this book. Although this novels has its flaws, it does provide a sense of wonder by not revealing or explaining everything. It leaves a lot to the imagination, and a sense of strangeness pervades the book. In plot, the book concerns an artist going back to Earth with robot companions 10,000 years after nuclear holocaust. Earth in this time is predominantly run by The Cemetery, the organisation that runs the cemetery, which is now the primary purpose of the planet. However, The Cemetery are up to no good, and exploit various 'back-to-basics' human tribes to cause problems for our heroes. It's a nice idea, although the introduction of a time travel device in the second half of the book didn't quite work for me. I felt this was slightly clunky and didn't sit especially well with the preceding plot. That said, I think Simak did a pretty good job layering ideas and concepts. I certainly wouldn't criticise it for lack of depth or consideration. I found the ideas that Simak plays with, concerning the wisdom of seeking the past and the meaning or importance of memory, to be interesting. So, for style and interest it scores well, for the overall satisfaction of the plot, perhaps a little less well.

City - Novel, 1952 (fix-up from stories written 1944-1951)

City is recognised as classic SF: it's in the SF Masterworks series and generally considered to be among Simak's finest earlier works. I enjoyed it for a host of reasons, and I'd agree it was very good. As a 'fix-up' novel, it derives from 8 short stories Simak published between 1944 and 1951. These are connected throughout not by a single individual, but across 11,000 years through one family (the Websters) and their robot. The earlier stories stand up very well as shorts in their own right. Indeed, "The Huddling Place" is a classic and one I've read a few times. As the book progresses, the stories increasingly rely on the reader having read the previous 'tales' and the sense of a continuous novel becomes stronger. Simak also did a clever thing to glue the stories together: he interspersed 'notes' to each tale as if written by the dogs who now rule Earth (and who can barely remember man). It is in these notes that a lot of my pleasure in the book came. These give Simak the opportunity to present his thoughts and ideas in a direct manner and he clearly enjoys the opportunity. From one 'note' for example came the following, that I think is wonderful:

"...it becomes clear than Man was running a race, if not with himself, then with some imagined follower who pressed close upon his heels, breathing

on his back. Man has engaged in a mad scramble for power and knowledge, but nowhere is there any hint of what he meant to do with it once he had attained it."

The collected short story structure also allows Simak to show us the long history of the downfall of humans across centuries in a relatively short novel. With such a grand story arc, one gets a good sense of the passage of time and this helps to impart the sense of loss when the humans move on or die out. So, on the plus side, this book is written very well, it presents some great ideas, and has pithy nuggets of wisdom to think about throughout. However, there is one aspect of the book I struggled with slightly and that is the degree of disbelief I was asked to suspend as a reader. The "uplift" of dogs and other animals, even ants, stretched credibility for me. Likewise the happenings on Jupiter seemed a bit unlikely. I have to remind myself though - Simak came from a generation before the golden age (and this is from the golden age), in which anything was possible, and 'hard' SF as a concept had not formed. To Simak, SF is a literature of ideas, of strange and fantastic futures, and not constrained by what might actually be possible. He writes of the future, but with one foot in fantasy, perhaps. I just need to readjust my SF barometer slightly to accept intelligent ants and dogs chatting to wolves. So, if you can leave your 'hard SF' goggles off, and just come along for the ride, I think this is an excellent book, full of ideas and it will stay with me for a long time, I'm sure. If you want to just dip in and read one or two tales, I'd recommend "The Huddling Place" and then perhaps the short tale "Desertion" as being the best of the bunch.

Shakespeare's Planet - Novel, 1976

One of Simak's later and shorter novels, Shakespeare's Planet is to be highly recommended. It doesn't attempt to convey a depth of message to the degree that more serious works like City do, and for its lightness of tone it could be under-rated, but this is an excellent SF novel. At under 200 pages, it manages to pack a lot in: planetfall on a distant world, the psychological effects of being displaced in time from long hyper-sleep, interesting aliens, a neat plot, love interest, action, mystery and that ever elusive 'sense of wonder'. Simak commented in one of his interviews that the sense of wonder in SF comes not from the book, but from the reader, but it seems to me that some authors were very much better at evoking it than others. Simak was a master at it, I think. Of the books read so far in this little reading challenge (and I'm admittedly not far along), this ones tops the charts so far. It manages to combine cool ideas and considerations of what it means to be human (the author's speciality) with a fun plot and engaging characters. Its also is very funny here and there. The alien "Carnivore" is a hoot, while managing to avoid being presented as a pastiche or a joke. I was a bit worried 20 pages from the end when there was still so much plot left to tie up and I was half expecting a disappointing conclusion, but Simak managed to conclude the book well in the few pages he gave himself; a master of brevity - some modern authors could do worse than look at how he did it.

Time is the Simplest Thing - Novel, 1961

To cut to the chase, I enjoyed this novel very much. I'll need to read a lot more Simak to know if it's one of his best, but from my reading so far I would suggest it may well be. In style, it is quite distinct from the two later novels I've read from the 1970's - those are lighter, stylistically. By contrast, Time is the Simplest Thing is a denser book, with much more descriptive prose. The writing is still smooth and clear but it does read as a longer more substantial book, though it is still relatively short by page count. One gets the impression that Simak was trying to write 'great SF' at this stage of career. The title is perhaps a little disinenguous, as there is little time travel involved. Time travel does feature, but this is really a book about the evolution of the human race to a psychic stage of development. Simak is clearly interested in what he calls in this book psychokinetic or PK abilities. It was mentioned I think earlier in this thread that Campbell was nuts for 'psionics' and he encouraged many contributors to Astounding to write stories about psychic protagonists and the evolution of psychic powers. This is a good example of that influence, another famous example probably being the Mule in Asimov's Foundation stories. It's interesting to note that the only SF concept in this book is psychic power, because, in a sense, that's not very scientific! However, we have to remember that in the 1950's and 1960's there was a lot of interest in psychic phenomena and it was normal to write such stories in SF. This interest famously extended to other art forms around that time, of course, such as Miles Davis' 1965 LP recording, ESP. Simak described how he approached novel writing in various interviews, suggesting that he planned the first half very tightly, then let the second half more or less evolve as it would. I think this can lead to books that start very strongly and go slightly off track toward the end. Cemetery World is one I'd perhaps put in this category. However, although the first half is slightly tighter in this novel than the second half, it concludes very satisfyingly indeed. Simak wraps his story up well, and the overall sense when I put the book down at the end, was "What a cracker!" Again, as I found with Shakespeare's Planet, I had my doubts as to how satisfyingly the book could possibly be concluded when I got to within 20 pages off the end. I need to start having a bit more faith in our Clifford though, as he managed just fine.

Way Station – Novel, 1963

Much lauded, Way Station won the 1964 Hugo Award for Best Novel and in an online poll conducted in 2012 by Locus, the novel was voted 47th best SF novel of the 20th century (City, at 40th was the only other Simak to make it into the top 75). This is without doubt a good SF novel, and must rank as one of Simak’s better books. Overall, I was impressed, and enjoyed it. The plot concerns a man, Enoch Wallace, who fought in the American Civil War and was selected shortly thereafter by an alien visitor to Earth to man a “way station”, as the station manager. A network of way stations crisscross the galaxy and provide points to which the alien races can teleport to transport themselves between worlds. Enoch’s station (set up in his renovated house in Wisconsin) is different however – the position of a station on Earth is valuable to ‘Galactic Central’, but, Earth is not yet a member of the galactic collective of races. Man’s war-like tendencies are keeping her isolated. And so, Earth is simply a stopping off point for the various races of the galaxy, who perhaps stay with Enoch of a night before travelling on, and Enoch’s way station is hidden from all on Earth except for Enoch. In manning the station he is conferred with immortality, but is displaced by his isolation from what would have been his normal human life. The power in the book resides primarily with the pathos in Enoch’s situation. His loneliness is well captured. To be within his family home, but at the same time feeling so isolated from humankind, he feels neither human nor alien – like a hybrid being with no single purpose. He vacillates in the book between feelings of loyalty and understanding of the aliens, and the pull of his human roots. His daily walks for the mail, and interactions with the deaf and dumb girl who lives nearby are touching. I felt it was those passages where he reflects on the passing of time, and the loss of family and his weakening connection to the Earth that were most successful. The plot idea of the way station is also successful and well realised. Various aspects of the book are very ‘Simakian’, of course. The pastoral landscape of Wisconsin is well described and the protagonist is an 'everyman' figure. The overall feel of the book is of a gentle pace, and Simak manages to convey the slow passages of time for Enoch very well through his occasionally slow plot progression, coupled with Enoch's reflections on his situation. Rather than bore the reader, this approach of slowing the novel down at times delivers a sense of space and isolation and reflection in the reader to. To bring about a sense of time and wonder and loneliness in a short novel really impressed me. This is Simak writing at his very best. It reminded me in style of Time is the Simplest Thing, which also had more descriptive prose and greater depth some some other novels. It’s not entirely perfect though. I personally felt the ending (which I shalln’t spoil) was a bit too ‘big’. It resolved too much for the reader and was a little too tidy. For me, the greatness of the book was to be found in Enoch Wallace’s loneliness and sense of dislocation from humanity, and I would have preferred an ending that continued this theme a little further, and in which the denouement was a little less ‘galactic’ in scope. If you have built your story on the emotional response to the individual, then I’d prefer a conclusion that was at the level of the individual too. That said, I enjoyed the book, and the main themes are dealt with very well in the main. I suspect it’s the sort of book that will stay with me for some time, as numerous scenes are very memorable and well delivered. Highly recommended.

Why Call them Back from Heaven? – Novel, 1967

My copy of the novel "Why Call them Back from Heaven?" manages to combine what I feel may be the best SF novel title of all time, with possibly the least inspired and interesting cover illustration of all time (a Science Fiction Book Club hardback from 1968). The novel, however, is a corker. Humankind has bought into the belief and aspirations of the conglomerate "Forever Centre", which promises the chance of immortality in a second life. People save all their money to fund their future immortal existence, and fritter away this life with their eyes firmly fixed on this intangible promise. Forever Centre claim to be close to achieving two things: the ability to thaw out and resurrect the billions who are now frozen, and also to provide immortality. But is this really reality? Can it be done? Some don't believe the claims ("Holies", among others) and it takes a brave or foolhardy soul to question the all-powerful Forever Centre. The protagonist, Daniel Frost, is an executive at Forever Centre, but he sees something he shouldn't have and the totalitarian wheels of power quickly move against him. This reads almost like an Orwell story for me, in its fable against totalitarianism and it has a genuine depth to it. Simak is clearly on his hobby horses, here - be careful what you wish for, and don't dwell on a possible future to the detriment of the present. The story arc is neatly done and much seems to be packed into a short novel, by today's standards; the ending is satisfying. Before I started reading Simak, I had heard of City and Way Station as being his best work, and I was not at all familiar with this novel. I'm very glad I came across it though - I think its the best Simak novel I've read so far - a short, unprepossessing work, but its a masterpiece of 1960's SF.

All Flesh is Grass - Novel, 1965

This novel comes from Simak's very productive 1960's, an era that I'm beginning to think of as my favourite from the author. In this time period he wrote serious minded, well crafted novels. I've really enjoyed later books from the 1970's, but he had become a bit more light-hearted and playful in his plots by then. From 1961 through 1965, however, all the books I've read have been excellent. The main plot idea of All Flesh is Grass may sound familiar: an invisible forcefield dome appears over a small town in rural America, trapping the inhabitants inside. Stephen King wrote a recent tome with the same premise of course ("Under the Dome") and its impossible to imagine King hadn't heard of, or read, this book, so similarly do they start. Funnily enough, my wife was reading the King book when I started this, and I looked up and said, "You wont believe this..." As an introduction to Simak, this novel would serve a reader well, as it delivers on all the themes for which he is best known: the small town semi-rural setting, our connection and interdependence with nature, the sudden appearance of aliens who come to us rather than us having to jet off to find them, the story focus on a normal 'everyman' protagonist and an extreme inventiveness. Simak often seems to present a story that at first is local in its geography and importance, and then later on he reveals a cosmic importance to his plot. This was the case I felt with Way Station and it is the case here too. Its probably closest to Way Station of all the books I've read of his in tone and ideas, too, so if you liked that, you should like this. I felt it was strong novel and I'd certainly recommend it. It's an awful lot shorter than Stephen King's take on the premise too!

They Walked Like Men - Novel, 1962

Sitting in the Simak bibliography time-wise between Time is the Simplest Thing (1961), and Way Station (1963), this novel comes from the heart of the authors highly productive early 60's period in which he stretched himself to bring a real sense of depth and refection to much of his work. It's strange then, that They Walked Like Men reads rather more like pulp fiction than either of those two novels in my opinion. Essentially, this is an old-fashioned alien invasion story, with a solution to the problem that, while not exactly appearing from thin air, nevertheless has a slight feel of deus-ex-machina about it. War of the Worlds, Simak style, if you like. The writing is quite good, but not quite to the standard of his best prose. It has the usual hallmarks of simplicity and direct storytelling, but fewer lines of really evocative description that he can do so well. The plot is quite interesting - positing that aliens may try to take over the Earth through economic warfare, not militarily, and like many Simak novels, he starts the story well and brightly. I've found in fact that most Simak novels start wonderfully well. It's the conclusion that sometimes proves the weakness in his books. In his best books, he does manage to conclude them well (often with startling brevity but neat as you like). Other times, and this is perhaps one of them, they almost seem to peter out. It certainly looks from what I've written that I didn't rate this book. Not entirely true; there is much to recommend it, and it would actually be a good introduction for young readers to the author. While I felt the writing was, on average, not quite up to the standards I know he can reach, it was nevertheless very readable, and there are certain passages that were highly successful. The scene were our protagonist senses his ties writhing in the closet with otherworldly life was superbly done, for instance. For the central idea and the first half I would say it's fine SF; but the overall execution and pulp fiction feel let it down slightly; I would therefore say it's a novel of middling quality in the bibliography, despite being a 60's novel of very high repute.

The Goblin Reservation - Novel, 1968

In the early 1960's, Simak wrote numerous books that have a depth and seriousness that appeals to me. He combined his ideas of a lost pastoral life, the our place in the universe, and the peculiar nature of time to write very fine SF. Toward the end of the decade he seems to switch a little bit to a more whimsical and entertaining style, and this is the type of book The Goblin Reservation is. There are pros and cons to Simak's less serious work, and like all 'art', sometimes it works well and sometimes less well. For me, The Goblin Reservation is probably the weakest of his books I've read to date, though its not entirely without merit. Firstly, it must be said that this book could not be mistaken as written by another author. If the cover and title page were missing, one would immediately latch on to the fact that it takes place in Wisconsin! There are many other parallels with other books too: there are aliens, but they are weird and Simakesque; the action is all on Earth; Shakespeare features (in fact there are several similarities to Shakespeare's Planet in the plotting); and while there isn't a dog, but there is a pet as a main character. Myth, fantasy and SF collide, and the writing is clear and readable. These are all Simak hallmarks. Unfortunately, the plot, for me, is just too daft, it's told too quickly, and offers to little in the way of introspective thought and comment that I enjoy most about Simak. In one fan poll, this is his fourth most popular novel, but I don't accord it the same merit. In contrast, Shakespeare's Planet, which on the face of it is similarly light and fantastical, and which has similarities of plot, is somehow a much better novel. A fun, light read perhaps, but for die-hard fans only I think.

The Autumn Land and Other Stories - Collection, pub 1990

Having read Simak's short stories individually as I came across them to date (primarily in old original copies of Astounding and Galaxy), it was interesting to read a collection of his work in one go. This particular volume was a Mandarin imprint, edited by Francis Lyall, whose introduction was welcome and informative. The 6 stories span 1938 through to 1971 and provided a lot of enjoyment. On the whole I recommend it, and I'm left wanting to read more of his short work. The individual stories do vary in quality though and deserve a few specific comments:

Rule 18 (1938) is the earliest offering here and while it has a strong whiff of 'men in hats SF', it is worth a read for three reasons: firstly, it is the fabled story that Asimov criticised in the letters page of Astounding, only to re-read and reappraise after CDS actually wrote to him asking him what he might change about it; secondly, it was CDS' first foray back into SF, writing for Campbell after his early 6 year hiatus; and lastly, its not bad. The historical value of the story has been attributed to the implied criticism of segregation/racism and the solution the protagonists find. Thus, it was rather ahead of its time, perhaps, though when read now it shows least well in this collection, in my opinion.

Jackpot (1956) is a novella, being a little longer, and I did enjoy it. Simak wrote most of his stories on Earth (mainly in Wisconsin!), so its nice to read one set on another planet now and then. Typical Simak aliens and ideas here. Its a solid enough effort, but probably not up there with his very best.

Contraption (1953) is a small but brilliant gem. The idea is simple, but the execution is quite superb - it reads like Hemingway. Its probably the perfect Simak primer to recommend if you wanted to show someone what the writer had to say to world, and how good he was at doing it. It seems to me that there were stories and novels CDS took very seriously and those he didn't, quite so much. For the former, he crafted his writing and produced enchanting works of genuine gravity. For the latter, they read more like he had to get something out after a long day on the newspaper to pay a bill. This story, along with novels like Way Station, is definitely in the former camp, whereas Jackpot, in this collection, is a very solid example of the latter, perhaps.

Courtesy (1951) is a pretty good story, in that I think CDS was aiming high, and one can never fault that, but the result is perhaps not entirely successful, so its a solid B+. The themes are very Simakian - humanism and humility having an intrinsic value - and the characters are quite nicely drawn.

Gleaners (1960) is a time-travel story from the perspective of the company that employs trained travelers to execute jobs in history. I'm not sure what Simak was trying to say here, other than 'this story might be fun, hope you like it'. It was kinda fun, but it was popcorn, dated SF, and not one I'll probably re-read.

The Autumn Land (1971) is of course the title story for the collection and presumably considered the strongest story here. Funnily enough, its not - that gong goes to Contraption - but is does have some things going for it: its a very thoughtful story, with some wonderful imagery and there's obviously some depth, as well as trademark Siamkian introspection and pastoral themes on offer. However, it's also unclear, unexplained, and rather unresolved. It reads more like dystopian fantasy than SF and I'm rather in two minds as to whether it possibly great but I need to re-read it, or maybe a bit of a mess and over-rated. I could probably be convinced either way.

Immigrant and Other Stories - Collection, pub 1991

Having enjoyed the previous collection in the Mandarin imprint series, I read another in between other novels, and again, enjoyed the experience. The introduction by Francis Lyall in this collection focuses on 'Simak Country' - that land just south of the Wisconsin river, and east of where it joins the Mississippi. This farmland features valleys, ridges and woods that Simak refers to in many stories. I looked the area up on 'Google Earth', and have a good impression of exactly how it looks now. The 7 stories span 1954 through to 1980 and are a good representation of Simak's shorter work. A few specific comments:

Neighbor (1954) is a solid story and features that recurring CDS idea of an alien coming to Earth with a neutral or friendly intent. It would be a good introduction to Simak if you wanted to understand his typical output.

Green Thumb (1954) offers up the idea of how an alien might interact if it were plant-like rather than animal-like. I enjoyed this story particularly and, like the preceding story, it features the 'Simak Country' that Lyall discusses in the introduction very nicely.

Small Deer (1965) is quite a funny story that offers a strange alternative explanation for the dying out of the dinosaurs, with some added pathos at the end. A solid B+ kind of story, but not the strongest here.

The Ghost of a Model T (1975) is not exactly SF; I'm not sure what it is, though it's harmless enough. Not one of my favourites to be honest, though its kinda charming I suppose and enables Simak to question whether technology has made things 'better' - a theme I harp on about myself.

Byte Your Tongue (1980) - There are some Simak stories that manage to be timeless, thoughtful and relevant despite technological advances that may have been made since they were written. This isn't one of them; rather weak.

I am Crying All Inside (1969) is a very strong story. Written from the perspective of a semi-literate sounding, obsolete, robot, it is compassionate, moving and rather deep. Rather reminiscent of a certain kind of literature that gains power by having a 'backward' point of view or protagonist (think, The Sound and the Fury, or Of Mice and Men), this is Simak aiming high and being successful with it.

Immigrant (1954) is pretty good. It takes Simak rather longer to tell his story than is often the case (this is a 60 page novella), but the premise is an interesting one and its quite well paced. I enjoyed it rather more by the end than I did part way through.

The Werewolf Principle - Novel, 1967

The Werewolf Principle comes from the late sixties, after his spate of truly great early-sixties books, and has a similar 'feel' to Goblin Reservation, which he wrote a couple of years later. It's an interesting book, as Simak applies science fiction thinking to create a situation in which a returning astronaut appears to be a werewolf. This is a theme Simak will return to in Goblin Reservation - the use of science fiction to recreate fantasy tropes in a way that can be explained by science. I suggested it was interesting, but I'm not sure its a literary trick I care for all that much. At the start the novel is slightly confusing, to reflect to confusion of the protagonist Andrew Blake (the werewolf). For me the first half of the book is only partially successful. It has some nice moments of tension, but there is too much hard work visible on the part of author to explain the strange situation. Its as though the idea was slightly too difficult to get on paper in an ideal way. The second half of the book picked up for me, and now the scene was set there was more chance for characterisation, and more importantly some interesting thoughts on the meaning of humanity, home and identity. Moreover, the later passages of the book come across as undiluted science fiction, and it works better for it. Overall, I would say it is not one of Cliff's best, but I did ultimately enjoy it as an interesting diversion. Its better than Goblin Reservation, but falls someway short of his best novels which have an effortless grace and a greater depth to them. This seemed rather forced by comparison. That said, its not a difficult read, it has some entertaining action scenes, it ties up quite nicely at the end, and at the end of the day its Simak, so there's a minimum quality in the writing we can rely upon.

Ring Around the Sun - Novel, 1952

This is an older novel by Cliff, predating his golden patch for me (mid-60's to early 70's). I enjoyed the book and it's very 'Simakian'; much of it set in semi-rural or small town Wisconsin, and it covers a lot of the themes of his most famous works: who we are, where are we going as a race, and what is time and can we exploit it. On that basis, its hard to see how a Simak fan wouldn't enjoy it. It also has the advantage of being quite short and pacey. I'd say it was a solid B+ novel, without being quite at the top of tree. For those who are not fans of Simak, or who have not read him, I'm not sure I'd recommend it especially, however, at least as a first book to try the author. The central SF premise is nice enough, but the simplicity of the 'scheme' and how this hoodwinks the civilized world for so long is not entirely tenable. This is perhaps SF showing its age, as the reader must suspend a sizable amount of disbelief, not from the SF aspects so much, as from the idea that the plot would develop as it does. Its all too neat , coincidental and unlikely to work out. In Way Station or All Flesh is Grass, the plotting makes much better internal sense, even if the premise is extraordinary. The twist at the end of this novel was also quite easy to spot coming, as the alternative we are supposed to be diverted by is so obviously sign-posted we don't believe it for a moment. All of which sounds rather negative, but I mention these reservations to explain why this is a B grade novel, not an A grade classic. Its still enjoyable, it's quintessentially Simak's style of pastoral SF, and the idea is probably a bit of a classic, so fans of SF history and development would enjoy the romp I'm sure.

Destiny Doll - Novel, 1972

Destiny Doll is, one the one hand, quite unlike much of Simak's output, and on the other, still very recognisably 'Simakian'. If you wanted an example novel to go along with a definition of what is science-fantasy (rather than straight SF), here it is: Destiny Doll. A young, rich woman hunter of alien big game (Sara) obtains the services of a cynical Starship captain (Mike), who is himself on the run from his misdeeds, to seek out a fabled adventurer (Lawrence Knight) who left known space many years ago in search of something. Sara and Mike are guided across the galaxy by a blind telepath, George, who hears a voice telling him where to go, and George's helper, an apparently weak and possibly fraudulent religious man, 'Friar Tuck'. Upon reaching the planet of their destination, they find they are held captive by the planet, and undertake a quest across its surface in search of Knight. On the face of it this sounds like a fairly standard SF plot, until you encounter the characters and witness the scenarios that befall the troupe. Helped by a strange alien (Hoot), our heroes are at first waylaid and then helped by hobby horses (yes, that is indeed rocking horses), meet centaurs, a robot who speaks almost entirely in rhyme, and are attacked by trees. And ultimately the destiny of our heroes is deeply affected by an ancient wooden doll. To say more would enter spoiler territory, but the fantastical elements here are clearly stronger than the SF elements. But as strange as all this is, Destiny Doll is a compelling read, and internally consistent. Reading like a cross between The Wizard of Oz and Through the Looking Glass, Simak uses his full imagination here to weave an intriguing plot, and inquire: what is it we are searching for and why? Is it a place, a thing or a feeling, and can our greatest desires fulfill us if they are isolated wishes, rather than being part of a social or group destiny? The allegories here give this book a depth and thoughtfulness that raises it above many SFF novels and Simak's prose is clean and clear as usual. Moreover, we are aided in accepting the utter strangeness of the planet by the cynical captain, who finds it all quite as strange as us and looks on it as a bizarre place he wants to escape. Also noteworthy is the fact that Simak's captain Mike Ross is a cynical no-good (at least at the start) which is unusual for Simak, but it allows the character to be the be both the foil to our disbelief in the planet and also provides Simak a flawed character who can ultimately find redemption. So, this novel is recommended - suspend your SF disbelief and enjoy the ride.

Our Children's Children - Novel, 1974

Published in 1974, Our Children's Children made for an enjoyable return to the worlds of Cliff Simak, though this is probably not one of his finest novels. A newsman sipping whiskey in a back garden sees strangely dressed people walking out of a dark 'door' that opens up at the base of an ancient oak tree. When this strange phenomenon continues through many such portals around the world, it becomes clear that the population of the future are fleeing their time to arrive in our present. It transpires that our children's children are fleeing their time to escape the ravages of intelligent hunter-killer aliens. The stakes in the present rise when it's appreciated that the aliens may also find a way back to our time. This sounds like a terrific concept, and a great opportunity for an exciting reading experience. However, while it is a decent read, it is tantalizing (rather frustrating) in the arm's reach stance it takes with the action, at least in the main. Simak's usual approach in novels is to focus on an unimportant 'everyman', usually a farmer or blue-collar tradesman. From this perspective he typically wrings a lot of emotion, pathos and homespun wisdom. In this novel, scenes skip between various points of view at a very high level: the President, the president's press secretary, an old-hand congressman, and so on. While there are scenes 'on the ground' they skip between different points of view, lacking continuity and a hold on the reader. As such it is less immediate and engrossing than Simak's finest novels that retain a tight focus at ground level. That said, there are interesting things here; Simak makes many more political points that is usual for him - not in a sense of left-wing or right-wing party politics, but in the sense of criticisms of social structures and the likely response of humanity to crisis. Overall, it's an interesting read, with a fair bit to enjoy, though it may be likely to disappoint ardent Simak fans who would perhaps expect something a little different.