Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions

Classic SF Anthologies edited by Harlan Ellison

Published in 1967, the SF anthology Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison, has legendary status in the genre as being probably the finest and most influential anthology of new SF stories ever produced. It set a very high standard, several of it's stories won major awards and the author list read like a who's-who of 20th-century SF. The success of the book led to Ellison repeating the editorial feat with an even larger sequel anthology, Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972. Each volume contained only one story from each contributing author, and there was purposefully no overlap in authors between the original anthology and its sequel. Dangerous Visions contained 33 stories, while Again, Dangerous Visions had a whopping 46. Ellison provided significant introductions to each story.

Dangerous Visions

Evensong - Lester del Rey

Del Rey indicates in his afterword that he see this, not as fiction, but as allegory. I'm not sure about that, as I think it's both. A short story, it tells of God, harried across the galaxy by the expansion and rejection of man. It's really quite effective and will prove to be memorable, I think.

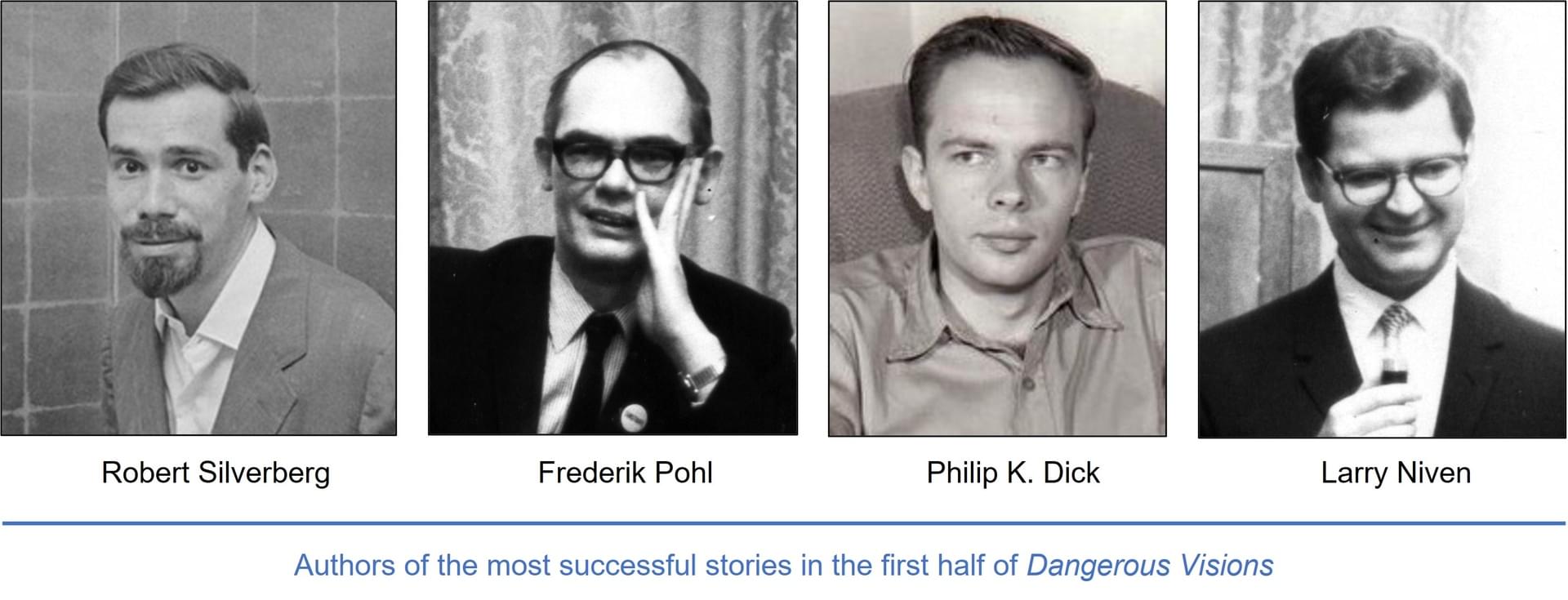

Flies - Robert Silverberg

This is a brutal story, in which a man is given the ability to take and transmit intense emotions by an alien power. He is sent back to Earth, where he feels compelled by the aliens to injure and devastate his ex-wives. Are we compelled to drain and suck the nature from those around us, like emotional vampires, or are our lives defined by a constant struggle to prevent suffering? Powerful stuff from Silverbob, who in 1967 was just entering his strongest decade writing SF.

The Day After the Day the Martians Came - Frederik Pohl

This tale, from Pohl, is very successful, I think. Martians have been discovered, and are visiting Earth. Reporters, tourists and hotel workers are gathered late at night at a motel near to Cape Kennedy to be close to the Martians' arrival. Several men trade jokes and insults about the appearance and likely intelligence of the aliens, drawing parallels with racist jokes aimed at American blacks. The final lines are very strong, making this is a low-key but superior story.

Riders of the Purple Wage - Philip José Farmer(Hugo Award Winner - Best Novella)

Farmer's lengthy novella has come to be regarded as a classic of the new wave. Written in confusing 'modernist' prose, the style is reminiscent of James Joyce's rather challenging books, Ulysses and Finnegan's Wake. Indeed, the main character, an artist in a surreal future, is named Winnegan. The 'purple wage' of the title, refers to the unearned income everyone gets from the state from birth. Without a reason to work for a living, an overpopulated society, that lives in cube city states, has fractured into artistic groups, fornixator addicts, and idle fido watchers. Farmer peppers the text with invented nouns and skips between perspectives in a dizzying way. It sounds as though it would be almost unreadable, but somehow it's not. I think the best approach is just to read it quickly and absorb the underlying meaning almost subconsciously. It's ultimately quite entertaining, and thought-provoking regarding the likely social structures we could be heading towards; however, it is certainly of its time and wouldn't be to everyone's taste. Ellison, in his introduction, suggests this is the finest story in the anthology. I suspect it may be the most experimental, which is not the same thing as best, though experimental and challenging is what Harlan was after, of course.

The Malley System - Miriam Allen deFord

Miriam deFord was 78 when she wrote this, having been writing SF and (mostly) crime fiction since the 1920's, but it doesn't strike the reader as a story written by a senior writer. Starting with a series of truly dreadful crimes seen from the perspective of the psychopathic perpetrators, the story goes on to suppose a possible futuristic method of treatment and punishment (the titular Malley System). It's a solid effort, with a strong conclusion.

A Toy for Juliette - Robert Bloch

This story by Bloch (the 'Stephen King' of the 40's-60's, and author of Psycho) starts a two-part sequence that imagines Jack the Ripper transported through time to a far future; the end of days. While being rather grisly, as one might expect with Bloch, it's a decent story. Ellison so liked to concept, having in fact suggested it to Bloch as a sort of follow on to his classic short story Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper, that he decided to write a sequel to this story for his addition to Dangerous Visions. This is the story that follows immediately after.

The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World - Harlan Ellison

So, we're back with Jack the Ripper, set in the far future in the final city of man, for Ellison's sequel to Bloch's tale. Ellison notes that he spent 15 months trying to get this story right, and he conducted a huge amount of research on Jack the Ripper to do so. He was obviously quite proud of it. The problem is, it's a further continuation of the theme of psychopathic violence and evil that defined the previous few stories, and its place here in the anthology makes the 'dangerous' element of the book seem like an increasingly narrowly defined, and unimaginative shift from normal SFF. Ellison would have been better to position his story later, or frankly, to have submitted a better story that sought the 'dangerous' moniker in a less obvious and unappealing way. This isn't, to my mind, one of Harlan's stronger stories as he emphasised shock value above everything else.

The Night That All Time Broke Out - Brian W. Aldiss

Harlan's introduction to Aldiss is rather damning with faint praise - one get's the impression he didn't much care for Aldiss, and didn't actually think a whole lot of this off-beat, humorous story. I could be wrong, but the tale is very silly, and lacking in any real sense. In Aldiss' future, most homes are on central gas time, and can set certain rooms to certain times using more of less time gas pressure. This works okay, until there's a time gas leak at a local mine. This sort of thing can be entertaining whimsy when it's done right, but Aldiss misses the bulls-eye on this occasion. And it's hardly a 'dangerous vision' so rather misses the brief.

The Man Who Went to the Moon - Twice - Howard Rodman

Howard Rodman (1920-1985) was a famous screenwriter, predominantly for television, best known for shows such as Naked City (1958) and Route 66 (1960), and he was a mentor to Ellison when the latter moved to Hollywood in the early '60's. This tale is gentle, mild and affecting, and really quite a good short story about how we lost our sense of wonder for the mysteries of the world with the advent of technology. It's not actually "dangerous" and it's not even in fact SF, being a non-genre story. But it is good, so it's appearance in this volume is a slightly odd, but welcome, aberration.

Faith of Our Fathers - Philip K. Dick(Finalist, Hugo Award - Best Novelette)

This novelette is quintessential Dick, with reality being questioned, and perspectives being affected by mind-altering drugs. It's also terrific. In a future in which the communist bloc is essentially ruling large parts of the world (including the US) in a dystopian autocracy, a Party man (Chien) is shown that everyone has been fed hallucinogens in the drinking water, in order that they see their dictatorial leader as a normal, Chinese man. But when Chien is given a drug that blocks the hallucinogen in the drinking water, he finally sees the leader as he really is - or at least as one of twelve possible (and horrific) realities. Highly inventive and gripping, this is a very good story, and shows Dick at the top of his strange, drug-fueled, game.

The Jigsaw Man - Larry Niven(Runner-Up, Hugo Award - Best Short Story)

Niven hit the ground running with his writing from the mid-60's onwards, and the reason is clear from this early story of his; the prose is so clear, fresh and readable, and the story so engaging, its impossible not to enjoy it. In Niven's future, organ replacement has become so routine, that criminals are executed even for minor crimes to provide the organ raw-materials. One man who has been arrested, and held in a cell between two 'organleggers', manages to escape from incarceration. The story is exciting and thoughtful. I have only one issue with it: Niven gets it all wrong regards the socio-political ramifications of organ replacement, which is perhaps surprising given he didn't have to look far into the future. Essentially it reflects a complete misunderstanding of the ethical parameters of healthcare workers, who would never countenance the kind of evil he envisages - but Niven is not a clinician and perhaps knew nothing of medicine ethics. This is a shame, because it makes an otherwise excellent story less than credible. One further general point regarding Niven: he apparently helped fund the publication of Dangerous Visions out of his own pocket, which Ellison was extremely grateful for - it would not otherwise have become published. By all accounts Niven was already a millionaire at the time and didn't actually need to make money from his writing (though he did). This story was runner up for the best short story Hugo Award, being pipped to the win by Ellison's own story I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream. Interestingly, Niven had won the award the previous year though, for Neutron Star.

Gonna Roll the Bones - Fritz Leiber(Hugo Award Winner & Nebula Award Winner - Best Novelette)

While Leiber's tale won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards for best novelette, I didn't think it was all that much. Ellison, in his introduction, tells us this story is a great example of why SF and fantasy cannot be separately defined. He was wrong - they can - this is pure fantasy. Being Leiber, the prevailing feeling was that the story should be more about the journey than than the ultimate plot, but this is a bit of a cop out here. The story has a certain style - it's slightly 'modernist', written in quite florid prose - but it's not especially well written in that style. Farmer's modernist effort earlier in the anthology is much more successful and otherworldly. Then we come to the plot and characters. The characters are all unlikeable, so we don't root for anyone, and the plot is messy. A gambling man goes out of the town and finds a new gambling den, in which he appears to play Death at dice (we later learn it's not Death). Except there are two characters who seem to be Death - Big Gambler and Mr Bones - which was unnecessary. The conclusion is rather silly the more one thinks about it. All-in-all, this is quite an effective mood piece, perhaps a B- story (its not awful by any means), but it does not merit the acclaim it's had over the years. The Philip K. Dick novelette reviewed above, which was beaten to the Hugo by this story, is a very much better story on every front.

Lord Randy, My Son - Joe L. Hensley

This story, by author and longtime friend of Ellison, Joe Hensley, bears some thematic similarity to the poem The Second Coming, by William Butler Yeats. A young child seems backward and abnormal, but can affect the world around him. His father, dying of cancer, feels both distance and love toward him. It's really rather good, and while it's ultimately quite a religious piece, it should have plenty of general appeal for its inventiveness and engagement.

Eutopia - Poul Anderson

Anderson doesn't seem to be able to write bad SFF, and I cannot think of anything of his I didn't enjoy - I can't say that about many authors. This tale, set in an alternative history of Earth, is quite compelling. It seems rather straightforward until toward the end, where Anderson starts to pontificate on how we value society and which societies are successful and which are stuck in ruts defined by egalitarian peace and unified thinking.

Incident in Moderan - David R. Bunch

The only author Harlan Ellison published two stories by in the anthology, Bunch is a strange character. Most of Bunch's stories seem to have been set in his 'Moderan' world, in which cybernetic humans fight constant wars to maintain the honour of hate. This story is more of the same, and is short, okay I guess, but nothing all that fancy. If you want to only read the best stories in this large anthology, skip it.

The Escaping - David R. Bunch

A second story by Bunch follows, which isn't set within Moderan. It's written in a 'modernist' style, which in this case can be interpreted as meaning, 'a bit rubbish'. I don't know what it was about, what happened, or why, or what Bunch was driving at. I could perhaps work it out if I read it through again, but frankly I doubt its worth it. This is the nadir of the anthology so far.

The Doll-House - James Cross

Cross was predominantly a crime/thriller writer, who submitted a story for the anthology at the request of an agent - Ellison had never heard of him before receiving the story. But this was pretty good. It's a fantasy tale of a dolls-house that houses the embodiment of an ancient Greek oracle. A man in financial straits uses the oracle to try and escape from his troubles. As a fantasy short story, it will surprise no-one to hear that it doesn't end well for him. As with many of Ellison's selections for the anthology, and in keeping with his preferences, this is more of a 'weird tale' than a SF story, but it was enjoyable, and some breadth to the contents is fine.

Sex and/or Mr. Morrison - Carol Emshwiller

This is a super little story, and is indeed (in agreement with Ellison's introduction) quite distinct in style to the other stories that precede it - Carol Emshwiller had a singular approach to writing it seems. In the world of the story, there are those who always hide their bodies, especially their genitalia, and those who do not, and the protagonist (a lady of senior age) is obsessed with seeing the male form for real. She latches onto the very fat man who lives above her as someone who might be 'other' and who might fulfill her desires.

Shall the Dust Praise Thee? - Damon Knight

Ellison's introduction to this story is a little odd, as it's essentially a roast of Knight, with the theme that the book would have been much better off if it included a story from his wife (Kate Wilhelm) rather than from himself. The tale itself is fairly typical Damon Knight, as it depends on a 'clever' twist in the final line, as opposed to much else. This is an anti-religious piece really, with criticism of the biblical God, Jehovah. My general feeling about Knight as an author, is that he was a good editor.

If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister? - Theodore Sturgeon

Ellison states upfront that this will be his shortest introduction, as Sturgeon needs no introduction. He then goes on to introduce it at some length, spending more time on it that most other introductions. Didn't Harlan proof-read the book? Anyway, this progressed like all the Sturgeon I've ever read, which is to say badly. I really don't get on with his writing, which is florid, often pretentious (as in this case) and unnecessarily obtuse. He also breaks the 'fourth wall' several times in the first few pages, directly speaking to you, the reader, about the story you're reading, which is an affectation I hate. Did not (could not) finish. So many other readers and authors cite Sturgeon as being a great writer. Maybe it's me and I have a Sturgeon-shaped blind spot, but I feel he was perhaps the most overrated SF author of all time.

What Happened to Auguste Clarot? - Larry Eisenberg

Ellison gave some pretty strange introductions to many of the stories (he couldn't maintain diplomacy for the entire thing, I guess!), but this one must win the prize for the most unusual. He essentially tells us that the story we're about to read is crap, and that the only 'dangerous' thing about it is that it's complete 'dreck'. I can only assume this was an in-joke, but yeah, skip it.

Ersatz - Henry Slesar

Henry Slesar wrote mainly crime and detective fiction for magazines, also for TV (Hitchcock TV shows) and may be unfamiliar to some SF readers. In a war-torn far future, individuals roam a devastated US, looking for enemies to kill or Peace Stations to hole up in. When one soldier finds a peace house, his wounds are tended and he's cleaned and fed. When he sees a woman there, following 4 years without female 'companionship', he roughly grabs her for sex. Nice. When she removes her clothes and he sees she is hairy on her chest and legs - presumably as a result of radioactive mutation - he punches her as hard as he can and runs away. This is the whole story, spoilers and all, so now you don't have to read it yourself. Execrable. Slesar confirms it was a 'previously rejected' story.

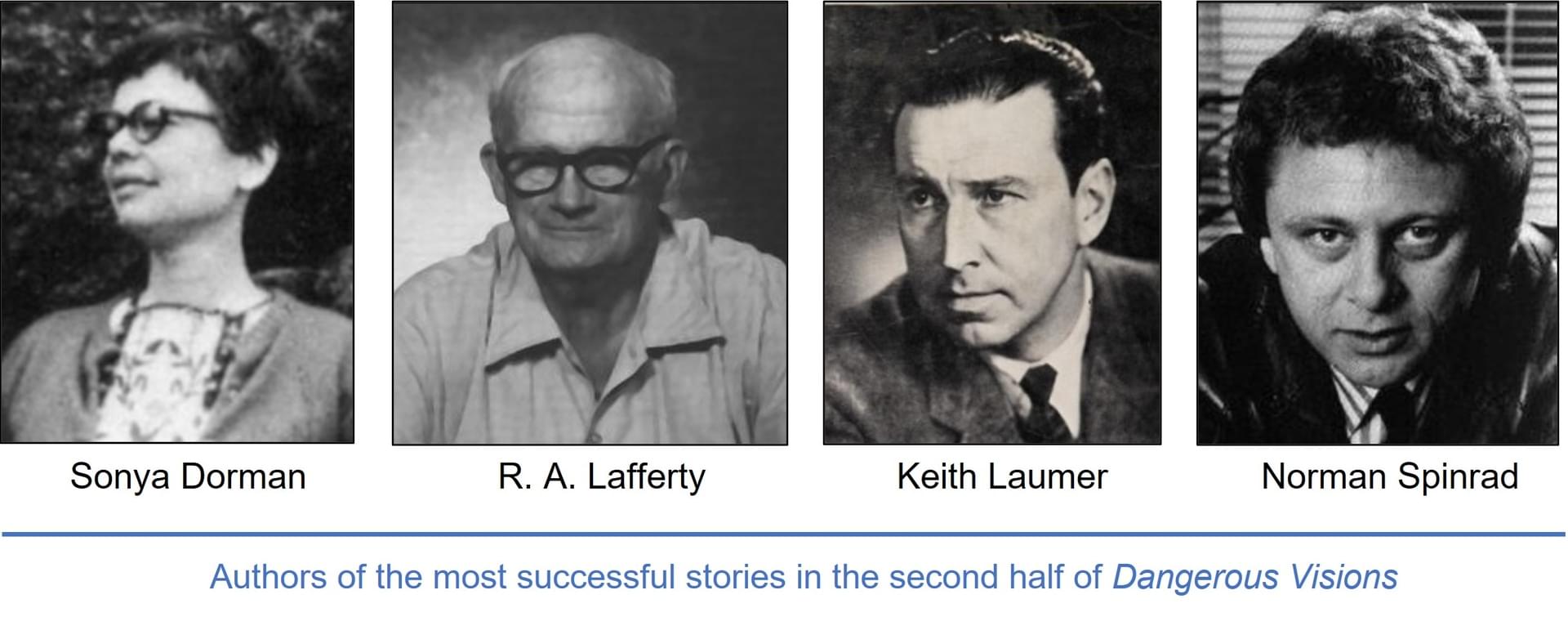

Go, Go, Go, Said the Bird - Sonya Dorman

This was really good, which was a relief after a run of three very poor offerings. In fact, it's as 'dangerous' as anything in the volume. In a dystopian future, humanity has receded to a cannibalistic society, in which the old or injured are gleefully killed for food. This story contains the most disturbing compound word I've ever seen composed in a SFF story: the protagonists son gains health and weight through consumption of 'Daddyporridge'. The story's title is from T. S. Eliot: Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind cannot bear very much reality.

The Happy Breed - John Sladek

I really enjoyed the Sladek novels The Reproductive System, and Tik Tok, which I read several decades ago, so I was looking forward to this. Sladek describes a 'horrible utopia' where machines keep everyone happy and safe, no one needs to work, and the uniformity and ease of life breaks the mind of everyone. It's rather well done.

Encounter with a Hick - Jonathan Brand

This is short, but quite effective, and ponders the religious assumption that a creator is necessarily superior, just because what's they achieved is on a large scale. Brand seemingly knew Ellison, and has attended writing workshops with the likes of Blish, Dickson and others, but it seems he only ever published three short SF stories, of which this was the last. I guess he didn't capitalise on his publication in Dangerous Visions. One of his only other two stories, Long Day in Court (1963), was anthologised in Fred Pohl's The If Reader of Science Fiction (1966).

From the Government Printing Office - Kris Neville

This tale is told from the perspective of a three and a half year old, who cannot wait until he's four, so he can start his education. His parents use fear and aggression to try and fix his personality before he hits the age of four - in keeping with official advice from the Government Printing Office. Quite effective, though nothing special. Neville died in 1980 at the relatively young age of 55. His most famous story was perhaps Bettyann (1951) which has been anthologised a good deal.

Land of the Great Horses - R. A. Lafferty

So we come to the most unique of SF authors, Raphael Aloysius Lafferty. I love Lafferty's style and thinking; he's just so odd-ball and different to everyone else. In this story - which is super - he supposes a slice of the world that was originally home to the Gypsies was suddenly removed, leading their nomadic lives. Where he goes from there is kinda genius. The ending is funny but also deep. I need to pick up a collection of Lafferty's best short fiction, as I've never read any of his work that didn't both flip my mind, and impress, in equal measure.

The Recognition - J. G. Ballard

This is, hardly surprisingly, very Ballardian. A small drab circus comes to town at the same time as a larger, bright fair is already present. Run by a woman of indeterminate age, and a dwarf, the little circus comprises half or dozen or so barred cages on the back of horse-drawn carts. But's what's that smell, and what's in the cages? This isn't really SF or even fantasy; I suppose it's weird fiction. It is good though. Ballard writes with a spare kind of elegance, and his stories, like this one, are often memorable (and slightly disturbing).

Judas - John Brunner

Brunner conceives a future where roboticists built a near-perfect steel robot, to which acolytes conferred the name 'God'. One of the original roboticists seeks out 'God' to put an end to 'Him'. The story is quite strong, with points to make about how we apply Godhood to constructions, and mold the interpretation of events to suit stories that underlie faith.

Test to Destruction - Keith Laumer

Laumer's story (which is neither a Retief nor a Bolo story, which makes a nice change) is full of action and adventure, but also has an involved SF plot, and something-to-say. A future US dictator wants to capture the electoral candidate he just defeated to extract information from him under torture. Once caught, the dictator ties the victim to a mind-control chair for this purpose. But there's a complication: an alien presence with powerful mind-scanning and control capability, in orbit around the Earth, also taps into the captured man's mind, and a battle for mind-control takes place. Laumer's idea was to take a stress test, such as would be applied to a metallic component in engineering, and apply the same 'test to destruction' idea to a human mind. It's well done, and an exciting read. As an aside, it's interesting to me that Laumer includes a short passage that clearly references the Hemingway short story, The Short Happy Life of Francis McComber - I do enjoy a good hidden literary reference.

Carcinoma Angels - Norman Spinrad

This was excellent, and one of the best stories in the anthology; humorous, extremely engaging, and written with panache, this is one to seek out. A man of quite singular talents acquires incredible wealth, and then acquires terminal cancer. He gets straight to work to beat his death sentence, with all the money and resilience he can throw at it. Ellison notes in his introduction that Spinrad sometimes writes very badly (and cites his first novel The Solarians, as being unreadable), and other times extremely well. I'm not sure if that's true or not, as I've not read so much Spinrad, but this is in the latter camp in any event.

Auto-da-Fé - Roger Zelazny

This is a fairly daft piece, seemingly written as a pastiche of Hemingway's Death in the Afternoon, with motorcars replacing bulls and 'mechadors' replacing matadors in the 'bullring'. To have two pieces referencing Hemingway within the space of a few stories (though neither expressly say this) is interesting and coincidental, but Ellison may have intended this. This tale was diverting, but not 'dangerous' and not especially good in all honesty.

Aye, and Gomorrah... - Samuel R. Delany(Nebula Award Winner & Finalist, Hugo Award for Best Short Story)

This was a strange story for Ellison to end on - not because its particularly weak (its okay), but because it seems so divergent from Ellison's view's. The story concerns a 'spacer' who - by definition in Chip Delany's story - has been neutered, and his attempts to explore human contact and sexual opportunity in various cities in the world. The disconnect here is that Harlan was extremely effusive of Delany's talents in his introduction, but in which he also expressed homophobic sentiments. And this wasn't the first time Ellison was homophobic in his introductions: on two other occasions he referred to gay men as 'fags' in a very dismissive way. Presumably he didn't realise Delany was gay, or that his story of gender identity and confusion hinted at the same. Now, Delany was married at the time (albeit to a lesbian who knew he was gay) but one does wonder what Delany perhaps thought of Ellison's homophobia as expressed throughout the book. In any event, the story is okay, but mostly annoyingly written, and it was a struggle to read (as much of Delany's work is), so the anthology ended on a bit of a low.

Again, Dangerous Visions

Coming soon...