Welcome to Starfarer Science Fiction, an amateur fan site for SF literature. Under the various links you can find bibliographies of certain authors, various 'feature articles' including award lists, a few personal lists of recommended reading, reading order of SF book series and other SF book trivia that I've compiled as part of my hobby and enthusiasm for the genre. I predominantly read the 'classics' of the genre, so information and reviews will tend to focus on well established and 'classic' authors. As a reviewer for Tangent Online, my reviews of current SF magazines can be found on the Tangent site, but summaries and links to the full reviews can be found if you hit the Magazines link.

** LATEST SITE UPDATES - Sept 2025 **

Updated magazine review page with recent reviews published by Tangent Online, see here.

Currently reading Prixima, by Stephan Baxter.

YEAR SUMMARY 02 December 2025

2025 SFF Recommended Short Fiction - Tangent Online

At the end of each year, Tangent Online (for whom I review short SFF fiction), publish a list of the most highly recommended short fiction. From the print and online SFF magazines I reviewed over the course of 2025, these are the stories I personally recommended. 3 stars is the maximum rating, though even a no star 'rec' is better than most short fiction, as most stories are not notably 'recommended'. There were not a huge number of recommended stories this year, but this may be because I reviewed few issues of Analog, for example, which usually garners a fair few recs. It was good to see certain issues of Lightspeed were especially strong (especially Issue #182).

Short Stories

“NOT Optimus Prime” by Lorraine Alden (Analog, 3-4/25) SF

“Eyes Grown Thick on the World” by Will McMahon (Lightspeed

#181, 6/25) Fantasy

“Un-Pragmagic: A Tyler Moore Retrospective” by Spencer

Nitkey (Lightspeed #182, 7/25) Fantasy

“Finding Love in a Time Loop: A How-To Guide” by Leah

Cypess (Lightspeed #182, 7/25) SF

“You Knit Me Together in My Mother’s Womb” by Paul Crenshaw

(Lightspeed #182, 7/25) Fantasy

“Everyone Hates the Auditor” by Megan Chee (Lightspeed

#185, 10/25) SF

“Imperfect Simulations” by Michelle Z. Jin (Clarkesworld

#231, 12/25) SF

“Multi-Spatial Apartment Complex Malfunction Results in

Body Horror” by Reyes Ramirez (Lightspeed #181, 6/25) SF*

Novelettes

“The Code of His Life” by Owen Leddy (Analog, 3-4/25) SF

“With Only a Razor Between” by Martin Cahill (Reactor,

8/25) SF

“The Hole” by Ferenc Samsa (Clarkesworld #231, 12/25) SF

SHORT REVIEW 02 December 2025

Lord Valentine's Castle - Robert Silverberg

First published in 1980, Lord Valentine's Castle is the first book in Silverberg's series of books set on the giant planet of Majipoor. A man called Valentine awakes with an almost complete loss of memory and with no knowledge of who he is, where he is, or what he should do, he joins up with a travelling juggler troupe, crossing one of the mighty continents on the huge world of Majipoor. We learn fairly soon that he is the king (or 'Coronal') or Majipoor, but his body has been taken by a usurper, leaving his broken mind in another's body. The book thereon follows his travails as he works in the troupe as an apprentice juggler, crosses many lands and has numerous adventures on the way to seeking reinstatement as Coronal.

The book is very readable, as of course is almost everything Silverberg ever wrote, with a clean, approachable style and a depth to the writing that draws the reader in. The world itself, and the classification of this book is an interesting one. The different races on Majipoor are aliens to the humans and come from other home-worlds. Earth is mentioned in passing as the cradle of humanity, and certain SF technologies are mentioned (floater sleds, and energy rifles), but in the main this is a fantasy. One of Valentine's friends in his travels is a small alien wizard who casts spells. Perhaps these are SF-style psionic powers, but the boundaries between SF and fantasy are definitely blurred in this universe. I usually like a clear distinction drawn between fantasy and SF, but the mixture here works surprisingly well. It's perhaps the best example of 'science-fantasy' that I have read.

Overall, this is a super book (it was nominated for the Hugo Award for best novel in 1981), and it marked a return to form and popularity for Silverberg, who had taken time away from SF for several years since his very successful late 60's-early 70's writing period. This novel was followed by numerous sequels that continue the storylines of Majipoor. The sequence of the books in the cycle are as follows:

Lord Valentine Cycle:

Lord Valentine's Castle (1980) Novel

Majipoor Chronicles (1982) Collection

Valentine Pontifex (1983) Novel

The Mountains of Majipoor (1995) Novel

Tales of Majipoor (2013) Collection

Lord Prestimion Cycle:

Sorcerers of Majipoor (1997) Novel

Lord Prestimion (1999) Novel

The King of Dreams (2001) Novel

SHORT REVIEW 21 November 2025

Forty Thousand in Gehenna - C. J. Cherryh

Forty Thousand in Gehenna by C. J. Cherryh is a SF novel first published in 1983, and set in the author's Alliance-Union universe. To gte stright to the point, this is the weakest Cherryh book I've read and would not necessarily recommend it. The initial premise (of a new colony of humans settling a world that has strange lizard-like endemic lifeforms) is quite interesting and Cherryh develops the setting in the first 100 pages quite nicely. Unfortunately, the mysteries Cherryh sets up - i.e. whether the endemic life forms ('calibans') can communicate, whether they are sapient, and why some humans lose start to change (or lose) their humanity in living with them - are never satisfactorily developed or resolved.

The author explains very little, doesn't develop her ideas especially well, and there is not much tension except on rare occasions. The book skips decades or centuries between sections in developing a longer history of the colony, but the downside of this is that we don't stick with any one character long enough to care about them. A problem I've seen in many other Cherry books is that the author will often 'tell', rather than 'show'. This is especially noticeable in this novel. If a character decides to go and stay with the calibans for a time, they seem to do so without many misgivings, but we are later told that in doing so they are now in mortal danger. But the danger doesn't really surface or provide any tension, we just get oblique, clouded references to the danger, without any consequence. And if the danger was great, why put yourself in the position? Clear motivations are not given for actions, and we are left to try and make sense of what's going on, with little help.

With only forty pages to go, I decided I really didn't care what happened, and that there were insufficient pages left to provide a satisfying resolution and rescue the book, so I put it aside and moved on.

SHORT REVIEW 09 September 2024

Star Trek: Destiny Trilogy - David Mack

I've not read a great deal of tie-in SF, based on famous film franchises, but this series was hugely entertaining, and well-written, and I'm glad I gave it a go. The Star Trek: Destiny trilogy - comprising Gods of Night, Mere Mortals and Lost Souls was released between Sept and Nov 2008. Set in 2381, five years after the finale of the show Deep Space Nine, the trilogy is a crossover event featuring characters from The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Titan (notably, Ezri Dax, Picard and Riker).

While a knowledge of the Star Trek universe and the preceding shows and films will add to the enjoyment for most readers, this does standalone pretty well, and offers up a space opera that has some good new SF ideas, not only the rehashing of Star Trek tropes. The scope is huge, the stakes are high, and the action is almost continuous. Well-known characters speak and behave as you would expect them to, and so fans of the shows will also not be disappointed.

Without giving too much away, the story arc revolves around the fate and discovery of a Federation starship, that was lost 200 years from the present time. This plot is interwoven with a new invasion of the Borg, with all the threat that the Borg 'collective' brings. The plot is well-worked out, and ultimately satisfying. There are literally hundreds of Star Trek tie-in novels, but this seems to be both a very good jumping on point for the post TV-series books, as well as key crossover series that ranks highly among fans. Recommended for all lovers of space opera..

SHORT REVIEW 19 April 2024

Light of Impossible Stars - Gareth L. Powell

This is the final volume in his Embers of War trilogy, and I enjoyed the first two. This one, not so much. It started out okay, introduced some new characters and scenarios, and built on the fall-out from the first two books with the characters from those books. So far, so good. However... ultimately, this last volume in the series was rather a let down. When a book ends badly and it's the end of a trilogy, it taints the series as a whole. What was shaping up to be very good for two and a half books, turned out to be a weak trilogy when viewed as a piece, and I cannot now recommend it especially highly. So what was wrong with it? Well, several things, so let's look at them in turn:

(i) The first two books set up a significant and interesting dilemma, with well-developed characters on established sides of the conflict, and it was hard to see a way out for our heroes. How will Powell wrap this up, we wonder? This would take a very clever idea or plot-twist from our protagonists to rectify, it seemed. Easy apparently. The way out for Powell was not to think up a clever ruse for his existing characters, but to drop in new characters in book three that have almost magical, God-like power. It's a book-long Deus-ex-machina, in essence. If you set up a SF problem over two novels, you cannot resolve the problem with sudden god-like power from new characters, obeying new SF rules, in book three - it seems like 'cheating' to me.

(ii) A perfectly interesting character who'd had a good supporting role to play in the book - a character we love to hate - decides a few chapters from the end that they are unhappy, not for the perfectly good reasons we've read about for the past 200 pages, but because they are a transexual and are stuck with a gender they no longer prefer. What affect does this sudden transexual theme have on the plot? None whatsoever. This unheralded theme from left-field dominates a chapter, and is then barely mentioned again. I can hear the editor now: "Gareth, all the cool writers in SF have transgender themes and characters, could you shoehorn something like that in here somewhere?". It's incongruous, virtue signaling and it doesn't fit into the book. I have no problem with trans characters or themes of course, but all plot elements need to serve the novel.

(iii) The end makes no sense to me. I can't say too much without spoilers but, while the final actions of some characters made some sense as an idea - at one point - other subsequent outcomes mean they had no need to follow through on their desperate notion... but they do it anyway! Which had this reader want to cry out "WHY?" with exasperation.

After the enjoyment of the first two books, this was rather disappointing as one might imagine. Afterall Powell can write well, and his books are inventive and highly readable. But I do wish SF writers would only write trilogies when they have a great idea for the entire story arc, not just the start and middle. Alistair Reynolds has been as culpable on this front, from personal experience. More and more, I find I want to read either standalones, or otherwise never-ending series, of which there are many. Defined trilogies often seem to let me down - great premise, poor resolution. At least never-ending series have no conclusion so I'm unlikely to feel shortchanged at the end.

SHORT REVIEW 15 April 2024

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep - Philip K. Dick

This famous novel, published in 1968, served as inspiration for the equally famous film Bladerunner which was released in 1982 shortly after Dick's death. The novel focusses on a police bounty hunter Rick Deckard, who's job is to 'retire' androids who have escaped from their colony world and returned illegally to Earth. Deckard is given a list of 6 new Nexus 6 androids who are at large in San Francisco. All which will sound very familiar to those who have seen the film. But there are several key differences between the original book and Ridley Scott's film, with the book offering a deeper and more complex plot. This was a re-read after a space of about 30 years and I was interested to remind myself how the book and film differ.

While bounty-hunting is a key aspect of the plot, it is used here as a vehicle for Dick to explore the nature of humanity and the soul. In the book, Deckard spends as much time dreaming of owning a real animal, rather than only his electric sheep facsimile, as he does searching for and retiring androids. Moreover, Dick spends a fair amount of time on 'Mercerism' - a rather nutty religious movement - as a way of approaching the question of religion in maintaining a sense of community, but also control.

Many of the main characters in the film also feature in the book, including Rachael, Roy Batty, and Pris. However, in the book Roy is married to another android, exemplifying ways in which the book's androids are more human than they are in the film - yes, they only live a few years and are made not born, but in many ways they are quite human. They are not physically advantaged here either, unlike in the film, and almost seem to accept their fate when a bounty-hunter runs them to ground. In this way, Dick blurs the distinction between human and android, and asks, what is it to be human, and why do we both kill life that we condescend, and then paradoxically also mourn its loss?

The subtleties in the book would not easily translate to film, perhaps, and so the film settles for themes that are a little easier to digest. Both are great, but in slightly different ways. A criticism Harrison Ford has been heard to voice about the movie is that he played a detective who didn't seem to do much detecting. But in the book he does even less detecting! He follows a list of names and addresses provided to him, and then undertakes his job of retiring them - he isn't a detective, he's a killer. The purpose of Deckard is not to propel a detective thriller storyline, but to enable Dick to ponder on some of his favourite themes - the value we place on life (animal or human) and the question of what it means to be human. This is rather deep book, and is highly recommended to SF fans who've not yet read it.

SHORT REVIEW 01 April 2024

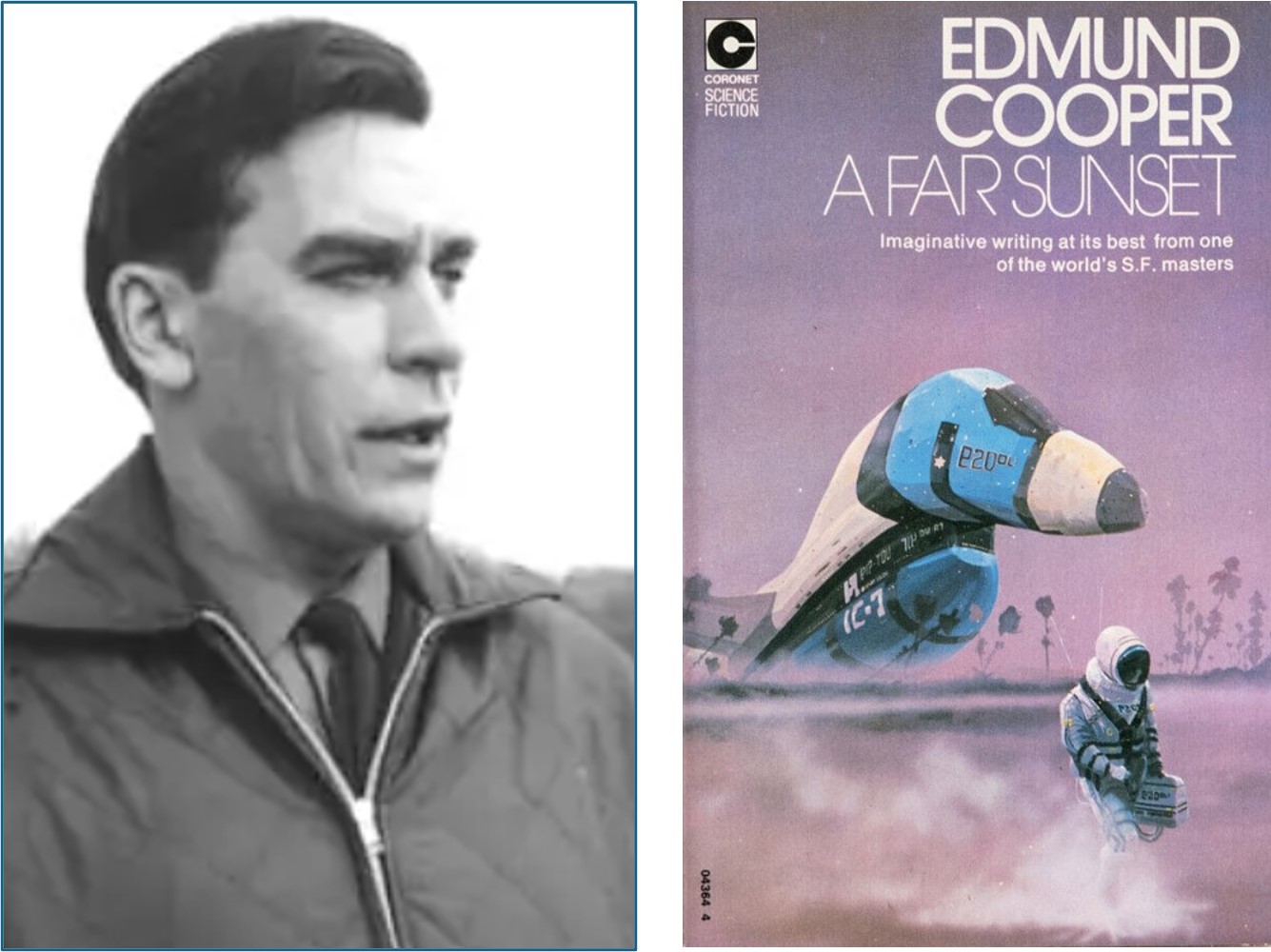

A Far Sunset - Edmund Cooper

Edmund Cooper's A Far Sunset (1967) is a superior short SF novel, and is generally considered to be one of the author's best. Several slower-than light colony ships leave Earth to find new habitable planets at various destinations, including the star-system Altair. Upon arrival after a 20-year flight (16 years of which the crew of 12 spend in deep-sleep), it is discovered that the planet Altair 5 is extraordinarily well-suited to support humanity.

However, after setting down, successive small exploratory groups that set out from the ship go missing, until we are left following a sole known survivor, Paul Marlowe. Marlowe falls in with an indigenous human-like alien race, who live according to extreme and terrifying religious rules and sanctions (coming across rather like ancient Aztecs). For the first half of the book, the prose styling and the narrative of the aliens and their way of life is reminiscent of Robert Silverberg's work from the same period. As the book progresses, and the central 'big idea' of the novel starts to become clearer, and it started to resemble Poul Anderson's style more. These similarities are to its credit; the book is well-plotted and engaging, and the characterisation is good.

Cooper wrote numerous good SF novels and his books are well-worth checking out. As well as this volume, I've very much enjoyed his novels The Uncertain Midnight (1958) Transit (1964) and The Overman Culture (1971) in recent years.

MINI REVIEW 05 December 2023

The Murderbot Diaries - Martha Wells

The Murderbot Diaries comprise an initial four short novels or novellas that between them create a single long story arc, followed by later publication of a longer novel and further novellas. These well-written tales by American author Martha Wells have gained a strong following in the genre. I read the first 'novella' a couple of years ago, and read the next two books this month. All were very enjoyable. Note, that, while most of these books meet the criteria for categorization as novellas, at 160 pages long they are actually as long as many 'Golden Age' novels.

The essential premise of the stories is that a security cyborg (a SecUnit) has managed to override its control circuits, enabling it to act with autonomy. Dangerously armed, and hugely competent, the SecUnit undertakes missions to unearth the background to its new autonomy and reveal the actions of the mega-corporation GrayCris. The stories are tightly plotted and well done.

Books in the series

All Systems Red (2017) - novella

Artificial Condition (2018) - novella

Rogue Protocol (2018) - novella

Exit Strategy (2018) - novella

Network Effect (2020) - longer novel

Fugitive Telemetry (2021) - novella, taking place between Exit Strategy and Network Effect

System Collapse (2023) - longer novel

The principle criticism of the books has been their price relative to their length. As novels, they are indeed short, and unless you obtain an e-book, you can only buy the second novella onward in an expensive hardback impression. Some have suggested this is gouging, and it's hard to disagree. That said, if you can pick them up cheaply (I got books 2 & 3 from a charity shop), they are great fun and well worth a read.

MINI REVIEWS 16 October 2023

The Sioux Spaceman & The X Factor - Andre Norton

SHORT REVIEW 07 October 2023

The Saga of the Exiles - Julian May

The Saga of the Exiles by Julian May consisted of four novels, published between 1981 and 1984. A common sight on SF bookshop shelves in the '80s, these books were highly popular and were a favourite of mine at the time of release. I re-read these recently and enjoyed them once more.

The Many-Colored Land (1981) introduces the plot and central themes. A few hundred years in the future, a time-travel device is developed near Lyon in France, but it only works one-way, and sends anyone who enters 6 million years into Earth's Pliocene past. Over the years many groups of 'exiles' enter this portal and take the trip back to prehistoric times, never to be heard from again. The first book follows one group of exiles (Group Green) on their adventure into the Pliocene. To their surprise, however, upon arrival they find prehistoric Europe is already inhabited by two related alien races: the Tanu (who enslave most arriving humans) and the Firvulag (who are the Tanu's traditional enemies'). Group Green gets separated up arrival, and we follow their adventures in two plot strands. The book is highly successful at both world-building and in the mass of great ideas that May introduces.

The Golden Torc (1982) further explores the adventures of the divided human Group Green from the first book. One half ultimately joins up with the Firvulag to try and topple the Tanu regime, while the second group, consisting of psychically-sensitive humans, travel to the Tanu capital. The Tanu have latent psychic powers, which they turn to 'operancy' through the use of special torcs around their necks. The most valued torcs (which leave the wearer free from Tanu control) are golden torcs. Several of the humans with latent psychic abilities become psychically powerful through use of gold torcs, including Aiken Drum, a young human misfit who turns out to have extremely strong psychic powers.

The Non Born King (1983) and The Adversary (1984) continue the tale, introducing further complications for the human groups in their relations with the Tanu and Firvulag, and in their efforts to either survive or gain supremacy over the alien races. These latter books largely follow Aiken Drum's role as the new 'King' of Pliocene Europe. Aiken wishes to build a new time travel device that will allow travel futurewards, so that those who wish to return to their future Earth may do so, but he is countered by another human of supreme psychic ability from his own time: the 'Adversary', of the fourth book's title.

The last two books delve much more into psychic thoughts, powers and mind-games than the first two books, which were more colourful from a world-building perspective. May's ideas are good in the final two books, but they feel less grounded and accessible. When the first two books followed characters who were themselves exploring and discovering all that was strange in Pliocene Europe, the reader felt the same thrill and immersion in the process. However, when we see everything from the perspective of highly powerful individuals in the later it is harder to connect and sympathise with their troubles and goals. For this reason, The Non Born King and The Adversary are rather less successful, though still immersive and well-plotted.

SHORT REVIEW 23 September 2023

Rimrunners - C. J. Cherryh

Rimrunners (1989) by C. J. Cherryh is a standalone novel set in the same Alliance-Union universe where the events of her more famous books, Downbelow Station and Cyteen take place. As is typical with Cherryh, the tale is told from a tight third-person perspective, as observed by the heroine of the story. An 'Alliance' marine is stranded on a space station, following her side's loss in a war, she can only get off-station by obtaining a berth on a starship from the other side. The story largely revolves around her personal challenges and relationships as she navigates the time she spends with a dangerous crew and cruel superior officer.

In many ways this book is rather good - Cherryh manages to make the day-to-day life onboard a starship come to life, and the characters and relationships are well-developed and nuanced. Cherryh is good at adding just enough detail to bring scenes and environments to life, without spoon-feeding the reader. That said, the main weakness of the book perhaps relates to the close third-person narration. We only see and hear whatever the protagonist sees and hears, as is usual with Cherryh's work, and at times this can baffle the reader. Exactly why certain events occur, and what the war's belligerents did to each other is either very slowly revealed, or in some cases, barely revealed at all. Cherryh fans won't find this a surprise and are likely to take it in stride, but many readers new to this approach may get frustrated and wonder what exactly is going on, and why, at times.

This is recommended, therefore, but with slight reservations. It doesn't have the depth or breadth of Downbelow Station, but it is nonetheless a step up from most space opera. Interestingly, I think the original cover art is dreadful (typical Baen pulpy fare), but it actually won the 1990 Hugo Award for best artwork, so I guess there's no accounting for taste!

SHORT STORIES 11 August 2023

Recent Short Story Recommendations

Below are listed a few of the best SF short stories I've read in the last 12 months. I routinely read many of the SF magazines as a reviewer for Tangent Online. It is intersting to note that, while I have read and reviewed from many magazines in the last 12 months, most of the recommended stories have come from Analog. Full reviews of these stories can be read at the Tangent site, with quick links found here.

The World in a Ramen Cup - Jayde Holmes (Analog Jul/Aug 2023)

After the Animal Flesh Beings - Brian Evenson (Tor.com Jun 2023)

The Belfry Keeper - S. L. Harris (Lightspeed #156 May 2023)

The House on Infinity Street - Allen M. Steele (Analog Mar/Apr 2023)

Immune Response - Robert R. Chase (Analog Mar/Apr 2023)

His Guns Could Not Protect Him - Sam J. Miller (Lightspeed #153 Feb 2023)

The Area Under the Curve - Matt McHugh (Analog Jan/Feb 2023)

A Real Snow Day - M. Bennardo (Analog Jan/Feb 2023)

Kingsbury 1944 - Michael Cassutt (Analog Sep/Oct 2022)

30 - Rich Larson (Asimov’s Jul/Aug 2022)

SHORT REVIEW 10 August 2023

I Am Legend - Richard Matheson

Matheson wrote his classic SF treatment of the vampire tale, I Am Legend, in 1954 two years before his excellent The Shrinking Man. Set in a postapocalyptic future, Matheson spins this exciting horror tale around the last surviving human - Robert Neville - who hides out at night in his boarded up house, from hoards of vampires that wish to kill him for his blood. This book differs from the common treatment of vampires, as they are envisaged to arise from a bacterial plague, with scientific justification for their powers and weaknesses. Moreover, this is not a tale of one vampire amidst a sea of humanity, but a sea of vampires surrounding a single hold-out survivor.

The book is short, but packs quite a punch, and would serve as a good exemplar for modern writers who feel the need to write huge tomes to encompass their ideas. Matheson has stacked this with subtle philosophy, as we hear Neville's thought's and appreciate his worries. As with The Shrinking Man, the central theme of the book is isolation from humanity; loneliness and the need for society are explored, as well as simply taking us on an exciting ride. Neville's nervous deliberations, his ambitions, and his despair ring true, and he's one of the most well-developed characters in SF.

For those who like to categorise books into clean genres, this book may present a problem. It probably meets the definition of horror, but it's much closer in spirit to SF. While the scientific rationalisations of the vampires might not convince everyone, that hardly seems important to the book; it's deep, well-written, blessedly short and highly recommended.

REVIEW 04 August 2023

Stranger in a Strange Land - Robert A. Heinlein

Stranger in a Strange Land is one of the most famous SF novels of all time. First published in 1961 by Putnum it came in at just over 400 pages, and at that size it was still unusually long for SF at the time. In fact, Heinlein had cut about 70,000 words from his manuscript followings howls from the publisher regarding the length of the book. I just re-read the novel, this time tackling the unabridged version that was posthumously retrieved from Heinlein's archives in the University of California. It is interesting to note that the reinstated material doesn't comprise added sections of plot or further chapters, but the reinstatement of all the adverbs, adjectives and other descriptions that Heinlein culled from almost every paragraph throughout the entire book! We therefore get a book that has exactly the same plot but with many more words. This leads to the first of a number of problems with the book; despite its reputation and Hugo Award win in 1962, I discovered it is in fact a flawed novel and one of my least favourite books by Heinlein.

I have checked the prose of the original published version with the unabridged version side-by-side. The original version has the advantage of moving things along much better, while the actual prose of the unabridged text is better written. Thus, Heinlein wrote a book that was flawed from the outset by its length. The full length version is bloated and progresses too slowly - the plot does not support the length - while the shorter version reads much less well. It's therefore hard to recommend either for different reasons, and Heinlein would have been well advised to simply write a shorter book that didn't compromise his prose in the first place.

The plot itself is an interesting concept: a baby (Michael Valentine Smith) is left on Mars, the sole survivor of the first manned mission to the planet, and is raised (rather like Tarzan) by the local Martian aliens. When he is recovered from Mars by a second mission a couple of decades later, he is essentially Martian in thought and perspective and when he's brought back to Earth, he is indeed the titular 'Stranger' to humankind. It's a decent idea, and the initial sections concerned with his incarceration in a hospital, escape, and early days in refuge are well done. We can sympathise with Smith's predicament and are interested to see how he integrates with humanity and learns our ways. From hereon however, the book goes downhill on a number of fronts.

Smith takes refuge with Jubal Harshaw, a lawyer, doctor, novelist and one the most smug characters ever written. Harshaw is Heinlien, basically, and the only character in the book with any character. Smith's ignorance of the world and human behaviour provides a mirror by which Harshaw can constantly comment and educate, generally in a biting, satirical manner. He offers logical insight into various topics, and a lot of what he has to say is quite clever. We find ourselves sagely nodding at many of arguments. However, this is supposed to be a novel about Smith, and Smith has no character to speak of, being both paper thin and unappealing. We therefore have a novel in which there is no main character: it's not actually Smith, who is a sounding board and acts like an automaton most of the time, and its not the peripheral figures either.

And here also lies the greatest flaw in the novel. Because he is Martian, and has no humanity to speak of, Smith cannot resonate with the reader. Harshaw has to provide all the human connection to the book. If Smith were to become more human as the book unfolds, he would become more engaging over time, and we could connect and sympathise more with him. But this doesn't occur - he remains Martian in thinking and outlook throughout, and moreover, all the other main characters join him, becoming more and more Martian themselves. By the end of the book none of the key characters have remained human in outlook, and we struggle to connect with anyone or any outcome.

The second major problem with the book is one of believability. Heinlein imparts other-worldly powers to Smith, such that he can make objects and people completely disappear just by thinking of it, he has telekinetic powers, he can adjust his body metabolism, change his physical appearance, and generally behave like a god. The rationale for all this is that he was raised by Martians, and that what we can do (from a psychic perspective) is simply dictated by our early learning and methods of thought. I didn't buy it; his acolytes can use all these powers after a year or so of practice even though they grew up in Boston, and this is glossed over. It's a weakness of the novel to my mind, given Heinlein is usually quite stringent on employing good science.

The final significant flaw in the book has to do with the incorporation of many of Heinlein's more controversial themes. The second half of the book centers mainly on the development and practices of Smith's church of 'All Worlds', and it is through this device that Heinlein offers various ideas for his readers - ideas that would become hobby horses in his later novels. Foremost among these ideas is free-sex and polygamy. This was the sixties, and he was writing for the zeitgeist to some extent I imagine, and these ideas are not that extreme by themselves. However, he dwells on the importance of free-sex and partner-swapping for a couple of hundred pages, which on the one hand becomes tedious, and on the other it strays into the unacceptable territory when Smith is arrested for statutory rape, for instance. The girls in the church figuratively roll their eyes when this occurs, as if to say, "good grief, he only had sex with underage girls, what's the big concern?" It's all rather unsavory.

In short, Heinlein wrote some terrific SF novels, but this is not one of them. It is either far too choppy in it's prose or otherwise far too long (depending which version you read), it has real promise at the start but peters out in its plot - which becomes increasingly self-indulgent - and it offers little humanity with which to connect. While the book did win the Hugo Award for best novel in 1962, that was actually against a backdrop of some severe criticism at the time of release. So, while I was surprised to find it is quite so flawed on this re-read (it was 35 years since I first read it), I should perhaps not have been too surprised.

SHORT AUTHOR SPOTLIGHT 07 July 2023

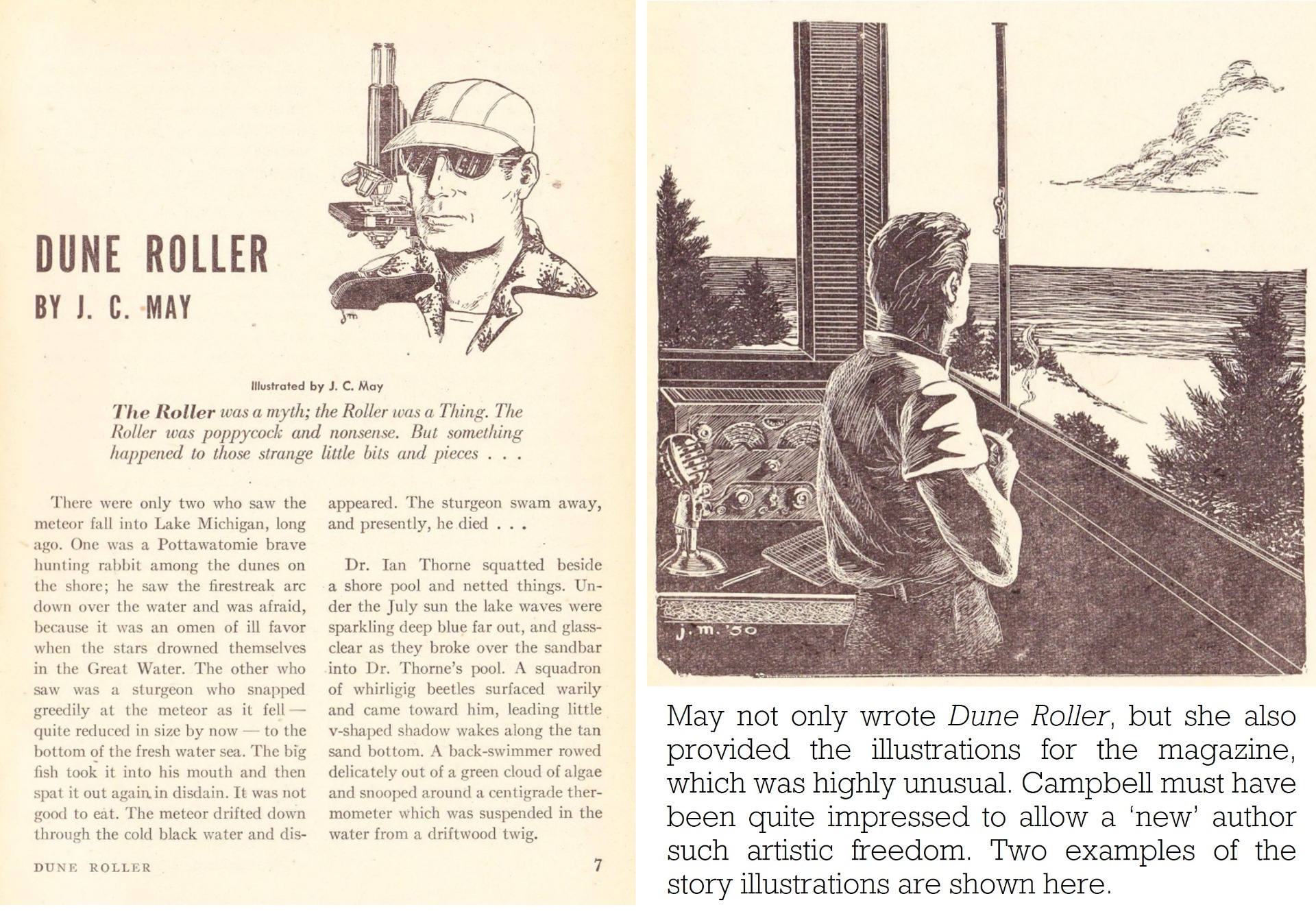

Julian May (1931-2017) and her 1952 novelette Dune Roller

Julian (Judy) May is most famous for her Saga of Pliocene Exile, and Galactic Milieu SF series (published between 1981 and 1996), though her background and some aspects of her life in SF fandom starting in the early 1950's are quite interesting. As I've started a re-read of the Saga of the Exiles, I started to look into her history and achievements in a little more depth and found out some interesting trivia nuggets. Born in Chicago in 1931, she became a fan of SF in her teens, and had several letters to the editor published by Campbell in Astounding when she was 17 and 18. Clearly enamored of the form and genre she was submitting to Campbell by 1951.

Her first published story was the novelette Dune Roller, which appeared in Astounding in December 1951, under the name J. C. May. There is perhaps no other first author publication which on its own has had had more impact for the author or the genre. Dune Roller is a very professionally constructed tale, splaying out like a B-picture monster movie, and containing all the tropes one might expect from that genre: The mysterious discovery of something unusual at the beginning; a scientist living on his own, pining for a lost love; the arrival of a new young woman to provide some love interest and sexual tension; the young woman being chased, the risky denouement, and so on. It's very readable and fun, and the writing is a notch above a lot of the work Campbell will have seen across his desk in these years, I'm sure.

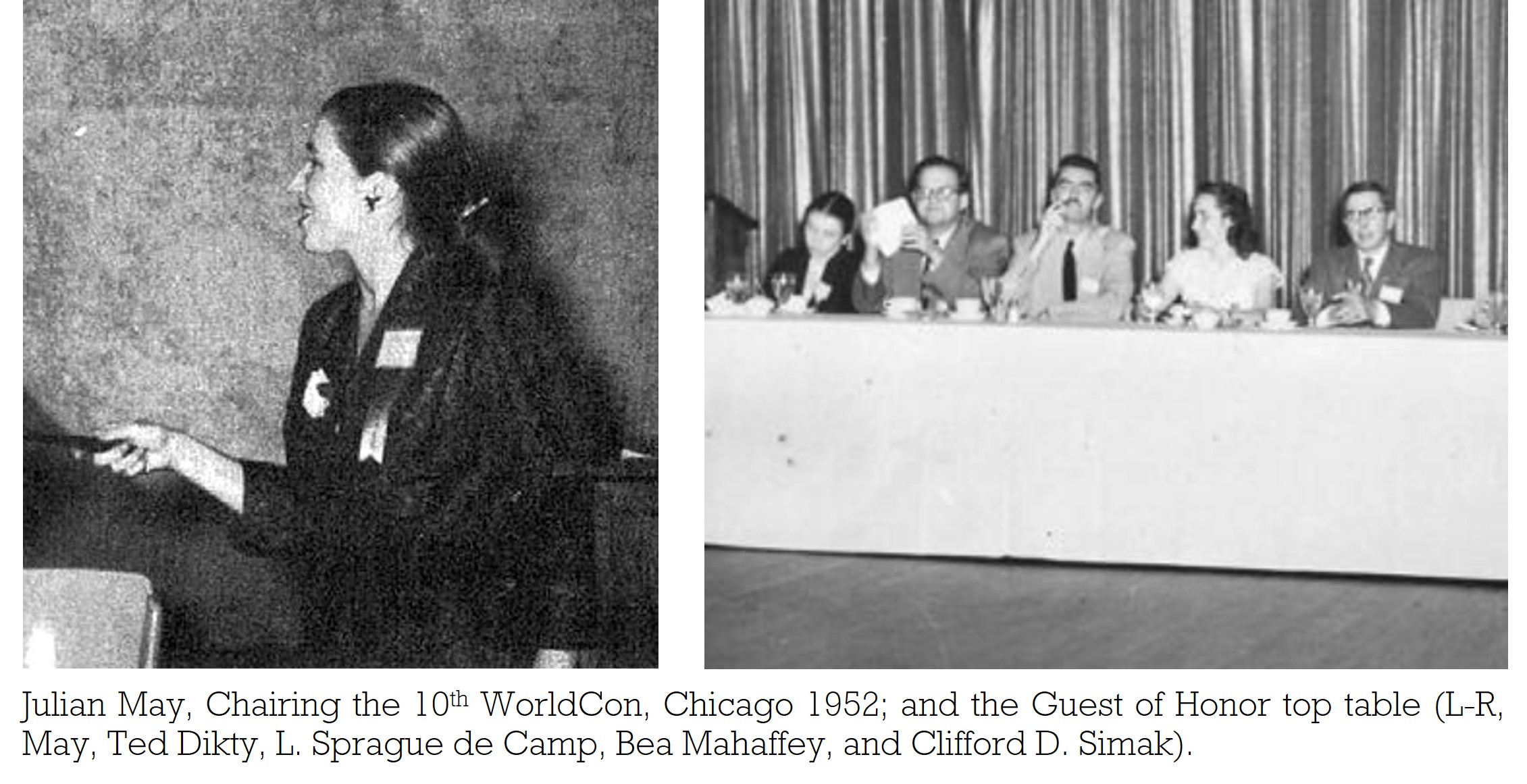

The impact of Dune Roller seems to have been quite profound. May had only one other SF story published in the early fifties (Star of Wonder, in Thrilling Wonder Stories, in Feb '53), and she then ceased writing SF until 1977. In the interim she wrote many children's books and science fact articles for various publications. And yet, on the back of her role in SF fandom in Chicago and the publication of Dune Roller, she was appointed Chair of the 10th World Science Fiction Convention in Chicago in 1952.

May must have done a pretty good job chairing the convention, though she was only 21 at the time and had only one published story behind her. The 1952 WorldCon is famous for several reasons: it was by far the best attended at that time, and its attendance was not surpassed until 1967; Hugo Gernsback was the convention's official guest of honor; the Hugo Awards were first proposed and adopted; and Sturgeon's Law was coined following his statement on a panel that "ninety percent of everything is crud".

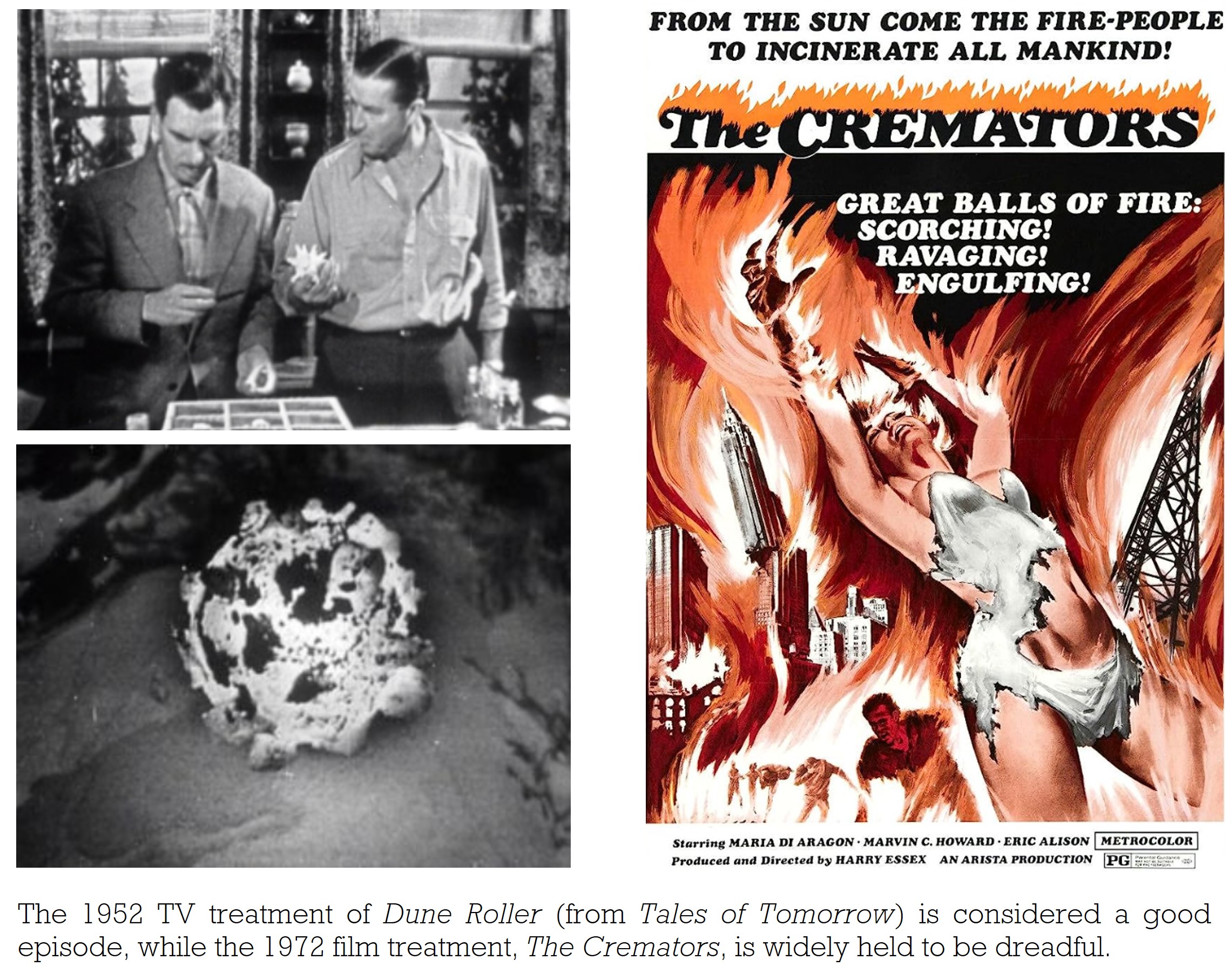

The influence of Dune Roller was not limited to May's success Chairing the '52 WorldCon, however, as it also received TV, film and radio treatment over the years. In January 1952, only a month after its publication by Campbell, it was used as an episode entitled The Dune Roller in the Tales of Tomorrow TV series (Season 1, Episode 15), with Bruce Cabot playing the protagonist Dr Thorne alongside Nancy Coleman and veteran character actor Nelson Olmsted. It is well reviewed as being one of the better 'Tales'. The episode must surely have been in development while it was 'in press' at Astounding, prior to publication.

The next treatment of the story in the media was by the BBC Home Service, who broadcast a full cast dramatisation of Dune Roller in 1961. It can be heard here. I cannot discover who the cast was for this, unfortunately. And lastly we arrive at a 1972 feature film based on the story, retitled The Cremators, and directed by Harry Essex. Garnering only 2.6/10 on IMDB, this is widely held to be a shockingly bad movie! The cast is of mild interest, however, as the leading lady here was Maria De Aragon, who also played Greedo in Star Wars (uncredited) and who co-starred in the 1973 version of Wonder Woman.

Clearly, given the multiple treatments on TV, film and radio, the story developed a reputation as a classic in the B-movie 'monster' subgenre. But as a piece of SF fiction it has also been treated well over the years, being collected in various anthologies by the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Silverberg and Isaac Asimov. Indeed, Silverberg chose it for a Treasury of SF Masterpieces, as late as 1983.

May married Ted Dikty (a SF editor and anthologist) in 1953, with whom she had 3 children and over the next 20 years she formed a small press, as well as writing thousands of science fact articles, and many children's books. Between 1954 and 1976 she stayed away from SF, but returned to SF fandom in 1976, attending Westercon 29 in Los Angeles. She clearly enjoyed the experience (going in space-suit costume), and started writing SF again. In 1978 she started on her most famous work, The Saga of Pliocene Exile.

The Saga consists of four books, which I ravenously read in my teens shortly after they were each published. The books are: The Many-Colored Land (1981), The Golden Torc (1982), The Non-Born King (1983), and The Adversary (1984). The broad concept is that in the future, a method of travelling 6 million years back in time has been discovered. But there are caveats - the trip is one way, non-one knows what Pliocene Earth is really like and the only place you can take the trip is through a distinct portal near Lyon in France. Exiles from the future galactic empire - those who don't fit in with their modern world - can travel back and take their chance in the distant past. The books follow a group of characters who take this trip of exile together, only to find that Pliocene Earth is actually sparsely occupied by an alien race from another galaxy. It's a terrific concept and is very well developed and written. I'm currently re-reading these books and will provide a proper review in due course. These books have a reputation as being quite 'fantasy' in their approach and feel, but having just read The Many-Colored Land, I can confirm they are indeed SF.

MINI REVIEW 22 June 2023

Our Children's Children - Clifford D. Simak

Published in 1974, Our Children's Children made for an enjoyable return to the worlds of Clifford Simak, though this is probably not one of his finest novels. A newsman sipping whiskey in a back garden sees strangely dressed people walking out of a dark 'door' that opens up at the base of an ancient oak tree. When this strange phenomenon continues through many such portals around the world, it becomes clear that the population of the future are fleeing their time to arrive in our present.

It transpires that our children's children are fleeing their time to escape the ravages of intelligent hunter-killer aliens. The stakes in the present rise when it's appreciated that the aliens may also find a way back to our time. This sounds like a terrific concept, and a great opportunity for an exciting reading experience. However, while it is a decent read, it is tantalizing in the arm's reach stance it takes with the action, at least in the main. Simak's usual approach in novels is to focus on an unimportant 'everyman', usually a farmer or blue-collar tradesman. From this perspective he typically wrings a lot of emotion, pathos and homespun wisdom.

In this novel, scenes skip between various points of view at a very high level: the President, the President's press secretary, an old-hand congressman, and so on. While there are scenes 'on the ground' they skip between different points of view, lacking continuity and a hold on the reader. As such it is less immediate and engrossing than Simak's finest novels that retain a tight focus at ground level. That said, there are interesting things here; Simak makes many more political points that is usual for him - not in a sense of left-wing or right-wing party politics, but in the sense of criticisms of social structures and the likely response of humanity to crisis. Overall, it's an interesting read, with a fair bit to enjoy, though it is likely to disappoint ardent Simak fans who would perhaps expect something a little different.

SHORT REVIEW 29 April 2023

Embers of War - Gareth L. Powell

I've recently tried to get into several modern British space-opera series as this is an area where I'd like to read more SF. However, in several instances, I've been disappointed, not by the quality of the writing but by the plots, story structure, and characters. This has led me to starting - but then giving up and not finishing - works by Alastair Reynolds, Adrian Tchaikovsky, and most recently Peter F. Hamilton. However, I figured I should keep trying. One of the most highly rated current British authors of space-opera is Gareth L. Powell, so in deciding to dip my toe back in the water, I picked up his novel Embers of War.

In this book we follow the crew of the decommissioned heavy cruiser Trouble Dog, a sentient warship that helped conclude the last war within the galaxy's 'multiplicity' through an act of planetary genocide. Trouble Dog and her crew, now part of a galactic search and rescue organisation, get a call to travel to a particular star system popular with tourists. There, they must recover any survivors of a space liner that has been shot down over a planet-sized sculpture. The central themes of the book are guilt for past actions, and redemption.

The ideas Powell introduces in this first book of a trilogy are top notch, and the characters are appealing, varied and rounded. This is also 'proper' space opera, with a huge scope, an excellent sense of scale, and a well-developed backdrop for this and future adventures. However, while Embers of War is part one of a series, it reads well as a standalone, with quite a satisfying conclusion - a rarity with many SF series. Embers of War won the 2018 BSFA Award for best novel. The second and third books in the Embers of War trilogy are Fleet of Knives (2019) and Light of Impossible Stars (2020).

SHORT REVIEW 17 April 2023

Foundation Trilogy - Isaac Asimov

As can be seen in a feature article on this site, the Foundation books began life as collections of short stories and novellas, published in Astounding Science Fiction, between 1942 and 1950. I've read these books several times, but the last time was almost a decade ago, so I thought it would be good to revisit the most famous SF series of all. Interestingly, I got new things from them, and it also occurred to me that they are collected in a strange way.

Foundation kicks off the original trilogy, and comprises 4 novelettes from the '40's, with an additional framing introduction added when the book was first published in 1951. The stories are interesting in several ways: they are used by Asimov to provide a space opera scope for some ideas of how war might be avoided, and they also are rather episodic. The first book therefore feels like the fix-up it is. I recalled more occurrences of Seldon appearing during crises, but in fact this only happens twice in the book.

Foundation and Empire, the second book in the trilogy comprises two longer novellas. The first of these is thematically and stylistically like the original stories. It's fine, but not especially engaging compared to what is to come. In some ways, this first story should be collected in the first book, because the second part of Foundation and Empire introduces 'The Mule' - the mutant who can control emotion in others and is a stylistic advance.

The Mule is a great invention, and once Asimov gets to this character, we can see that the author has developed a larger story-arc and a broader plan for the books. The plotting becomes deeper and better, and the whole starts to gather pace and interest. Asimov is able to introduce more interesting ideas while also making his galaxy of worlds come to life and gain scale. Interestingly, the first half of the third book, Second Foundation, also features the Mule as the lead character. The second half of 'Empire' and the first half of Second Foundation, would actually make a thematic whole, and might be a better way of collecting these stories.

Second Foundation is probably the most satisfying of the original trilogy. As well as concluding the Mule story-arc well, it provides an intriguing plot of the Foundation seeking the location of the Second Foundation. Asimov has a fair bit to say about clarity of thought, the value of clearly expressing ideas, and of the dangers of developing 'physical' technologies without developing thought and mental refinement in parallel. Overall, the story arc develops quite nicely across the three books, but the development of plot, breadth of vision and skill in execution clearly develops from the first through the third book. The second part of Foundation and Empire and particularly Second Foundation feel like Asimov classic books, while the earlier stories feel more like 'Early Asimov' in tone and execution.

SHORT REVIEW 05 April 2023

Like Nothing on Earth - Eric Frank Russell

Eric Frank Russell (1905-1978) was the first British writer to contribute regularly to Astounding Science Fiction, and he was the third most published author in that magazine in the 1950's (with 27 stories across the decade). Most well remembered as a SF humorist, he wrote both funny and straight fiction, and was highly readable. Another favoured author of mine, Alan Dean Foster, has said that Russell is his favourite SF writer.

Like Nothing On Earth(1975, reprinted with an extra story in 1986) collects 7 stories that all appeared in Astounding, between 1941 and 1957. The collection begins with Russell's 1955 Hugo Award winning short story, Allamagoosa. The tale is very funny, told with bright wit and crisp funny dialogue. Novelette The Hobbyist (1947) concerns the crash-landing and escape form a strange planet, and is rather good. The Mechanical Mice (1941) creaks a bit with age, and has less spark that later works but is quite good fun. Into Your Tent I'll Creep (1957) is far from the horror it suggests - the story of telepathic aliens is quite droll but doesn't live up to the great title.

Nothing New (1955) is rather good space opera though it ends somewhat abruptly, while Exposure (1950) is essentially a shaggy-dog story. It's engaging and the dialogue is excellent, though it all leads to a rather daft joke. The best story is kept to last, however, as Ultima Thule (1951) is really terrific. It has Russell's trademark smart dialogue that always amuses, but the story is essentially a serious one, and the SF idea behind it is top-notch.

SHORT REVIEW 04 March 2023

Cryptozoic - Brian Aldiss

Cryptozoic (1967) is an early Brain Aldiss book, written in the height of the 'new wave' of British SF, when showing how clever you were as an author seemed to be important. It's an interesting read, not because it's very good (it isn't) but because it manages to be both intriguing and dreadful in almost equal measure. Algis Budrys certainly didn't like it when, in his review upon release, he described it as "a useless book". However, for the first three fifths of the novel (or thereabouts) it is engaging, well-written, and follows an intrinsically interesting and novel take on time travel, and out relationship with time.

At the start we follow the time travelling adventures of an artist, called Bush. The concept here is that time travel can be accomplished with the mind - when properly trained and with the help of drugs - such that one can travel down time with the entropy gradient, which is easier the farther you go (such as to the Jurassic period) but is much harder closer to the current time. When 'mind-travelling' one can see the world and explore it, but not really touch or interact with it. Bush lives for a few years in both the Devonian and Jurassic, before returning to his present day, in 2093. This is where the book takes a turn for the worse.

Upon returning to the 'present day' Bush discovers that Britain is now under control of a totalitarian dictatorship. The book thus morphs into a 'thriller' of one man against the state. This could be fine, but Aldiss then throws out a further idea - that time actually travels backwards, and that humans only see it going forwards due to some form of mental conditioning. Aldiss spends a long time describing how this can be, without ever making the idea seem anything other than patently absurd .

Finally, when we've about given up on the idea the book might have any merit, Aldiss finishes with a coda that's a complete cop-out. The author himself noted this is "A novel that did not entirely hatch, the parts being better than the whole". I would tend to agree, though I'd be a little less charitable. The 'mind-travel' idea is really good and would support a very good novel. It's a shame he didn't write that book, as opposed to following additional and very silly ideas that ultimately comprised this one. One cannot help wondering if this was a case of an artistic novelist trying to write on a science subject of which he had very little grasp. I've been a big fan of Aldiss over the years, and he's written some very good work, but if you've not read him much, don't start here; try Greybeard, Hothouse or Non-Stop first.

SHORT REVIEW 16 February 2023

The Sirens of Titan - Kurt Vonnegut

The Sirens of Titan (1959) was an early novel of Kurt Vonnegut (1922 – 2007) and was nominated for the Hugo award for best novel in 1960. Like much of Vonnegut's output, it is a darkly comic and satirical tale. In its off-beat simplicity, straightforward language and bizarre plotting, it is reminiscent of Lafferty and in its humor of Douglas Adams.

In the future, Winston Niles Rumfoord, and his dog, travel through space and accidentally come into contact with a 'chronosynclastic infundibula' between Earth and Mars. This allows Rumfoord to travel in space and time and foresee the future. When he tells America's richest man, Malachi Constant, that he will travel to Mars, Mercury and Titan, he sets in motion a series of bizarre occurrences, including a hopeless attack by Mars forces against Earth. Ultimately, what transpires for both the 'space wanderer' Constant, and for humanity makes a strange kind of sense.

The central theme of the book is our fate as individuals and as a race - the nature of destiny versus free-will - and it explores the core meaning of being human. Vonnegut was very interested in the meaning of life; in a novel that questions this at every turn, he suggests at the story's end that it may simply be to love those around you. Undoubtedly an odd book, full of idiosyncrasy and silliness, it nevertheless repays reading, containing many delightful scenes, great wit and invention and will provide a fresh change of style from almost any other modern SF book.

SHORT REVIEW 16 February 2023

A Princess of Mars - Edgar Rice Burroughs

A Princess of Mars (1912) was the first of Burrough's Barsoom SF novels, featuring the American civil war hero John Carter. Set predominantly in 1865, John Carter is hiding in a cave from a large band of Apache natives in Arizona, when he is mysteriously transported to the planet Mars. Upon waking on the red planet (covered in moss, and with a weak but breathable atmosphere) he is first captured by fifteen foot tall green Martians. His strength and agility are greater than the natives, as Mars gravity is much weaker, and he attains an delicate position that is part captive, part chieftain. Later he discovers that the giant green Martian race is at war with the human red Martians, who whose capital is the city of Helium. Carter falls in love with the princess of the red-timited human Martian race, Dejah Thoris.

This book must be read as a product of its time. Of course the physics on show here is extremely daft, but there is a swashbuckling charm that excuses much of it. Burroughs' inventions of the eighth and ninth 'rays' on Mars manage to be especially silly, while simultaneously being fun and inventive. It is interesting that Burroughs doesn't attempt to invent a spaceship to take Carter to Mars - he simply arrives there. And when we come to characterisation, Carter manages to avoid being grating, despite his somewhat false humility and general perfection, as he takes himself so seriously and has a good heart.

A first publication in 1912 makes this one of the oldest SF novels I've read, and the benefit of reading such tales is that they provide the background for so much that followed. Without Burrough's Barsoom books we might never have seen the same 1930's emergence of SF pulp magazines, Buck Rogers, E. E. 'doc' Smith's series, some of Heinlein's output, and more recently it has continued to inspire comics, the recent film John Carter (2012), and other SF creations as Avatar, which James Cameron said was inspired by a wish to get back to John Carter's kind of adventure.

SHORT 'ACE DOUBLE' REVIEW 7 January 2023

Planet of Exile - Ursula K. Le Guin

Mankind Under the Leash - Thomas M. Disch

Ace Doubles were a fan favourite of the SF and fantasy genres, running from 1952 until 1978. Mostly published in tête-bêche format, with two short novels in each book, each printed each upside down to the other, and meeting in the middle such that each book sported a cover for each novel. This Ace Double was book G-597 in the series, published in 1966 and featured works by two literary figures in SF: Ursula Le Guin, and the new wave author Thomas M. Disch.

Le Guin's Planet of Exile was an early entry in her Hainish sequence (that later famously included her classic novel The Left Hand of Darkness). A colonised world has been abandoned for 600 years, leaving the colonists to exist in a state of exile in one city by the coast. This world has years that last 60 earth years, such that each winter lasts a generation. The natives are like humans, but are more primitive and split into two warring subspecies, When winter approaches again, one tribe's migration threatens the existence of both the colonists and the local natives. The novel is quite short, but Le Guin paints a crisp, clear picture of the world, and raises interesting questions of what defines humanity. A good read.

The second book in the 'double' is Thomas M. Disch's Mankind Under the Leash. The invasion of Earth in 1970 by non-corporeal, highly advanced alien's (attracted by the sun's particular solar radiation), has led to most humans accepting their position as pets to the aliens, living under a benevolent mental 'leash'. The life lived by 'pets' is comfortable and focusses on aesthetics. When an especially powerful solar flare knocks out the aliens on Earth, many pets are released from their 'kennels' and the leash they love so much. This marks a moment where revolutionary humans who have avoided the leash and live free as 'dingoes' can retaliate. The overall scheme is quite satisfying and its a nice idea. Disch was one of the foremost writers of the New Wave of SF in the 1960's and this shows through here. The book is full of half-serious, half jokey prose, and while its clear the work is satire in many ways, the message and plot is not really satirical. It therefore falls rather between two stools, and suffers somewhat as a result. If it had been a little less tongue in cheek here and there, it would probably have been better, but Disch's instincts to tear up the play-book in SF writing won through, one suspects.

For earlier years' articles hit the relevant archive button below

2022 Article Archive 2021 Article Archive 2020 Article Archive