Welcome to Starfarer Science Fiction, an amateur fan site for SF literature. Under the various links you can find bibliographies of certain authors, various 'feature articles' including award lists, a few personal lists of recommended reading, reading order of SF book series and other SF book trivia that I've compiled as part of my hobby and enthusiasm for the genre. I predominantly read the 'classics' of the genre, so information and reviews will tend to focus on well established and 'classic' authors. As a reviewer for Tangent Online, my reviews of current SF magazines can be found on the Tangent site, but summaries and links to the full reviews can be found if you hit the Magazines link.

BLOG ENTRY 29 December 2020

My Year of SF in Review

2020 has of course been a very difficult year for many, with a pandemic virus causing untold harm and preventing normal travel and activities. I've been very lucky to be in New Zealand at this time, and the only impact on my life has been to be house-bound at times. I know I'm lucky. These changes have meant a lot of time for many to read, however, and I'm hopeful that some have taken up reading SF. This year I've read reasonably widely, but I've still focused on 'classic' (i.e. older) SF in the main.

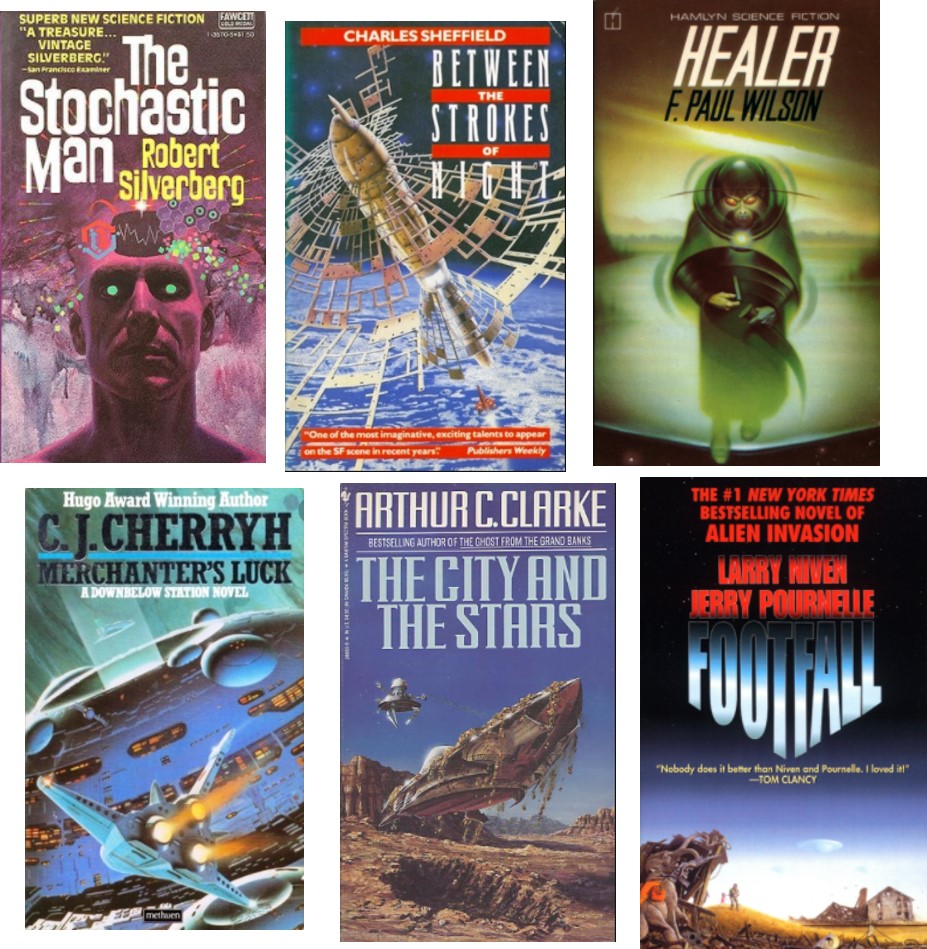

Earlier in the year (and before I started this website) I read several classic SF novels which I am able to heartily recommend including The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg, The City and the Stars, by Arthur C. Clarke, Healer by F. Paul Wilson, Merchanter's Luck by C. J. Cherryh, Between the Strokes of Night by Charles Sheffield and Footfall by Larry Niven & Jerry Pournelle. These were all good, and worth seeking out. Two of these probably deserve further mention:

The Stochastic Man, by Silverberg may be my favourite book to date by this author. It posits the question, if you know exactly the time and manner of your death, even if it's years in the future, how would that affect how you lived your life? I love stories that are about something, and this queries a basic fundamental to human life - that the requirement to strive and endure to unknown ends is essential to life's journey and to the value of our existence. In essence, its an existential novel, such as might have been written by Camus. A fine short novel.

Between the Stokes of Night by Sheffield is great, because it's space opera with big and novel ideas. In this book, the method of interstellar travel is enabled by the crew and passengers slowing their body clocks so much that their relative appreciation of time is massively reduced. But eons pass outside the ship. In looking at the relative time shifts between those travelling and those staying in one place, the book looks at how this affects humanity and relationships (in a similar way to Haldeman's Forever War). It was also a great plot and well written - I'll be seeking out more Charles Sheffield in future.

In addition to some great older books, I also read a few newer SF books. The book most worth mentioning here is A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine. This is not a perfect book, and falls short of being in my list of all-time favourites, but it did win this year's Hugo Award for Best Novel, and it certainly had positive qualities. The imago devices provide an interesting plot and they are a great SF idea. In addition, the characters are roundly drawn and appealing. There's more than a hint of Cherryh's Foreigner books in the dense political aspects to it, and this will be good or bad, depending on your view of those rather slow books. Much is achieved through subtle influence and pressure by certain individuals upon other individuals to bring big changes in the Empire. This gives the book a sense of depth and maturity, but I'm not sure it quite rings true - political change is actually more complex and harder to redirect than is implied. The apparently fluid sexuality that the main characters display is fine, but to have many of the main characters bisexual seemed unnecessary and artistically suspect. Lastly, my main reservation is in the pacing; while it has periods of excitement, it is patchy in this regard. In short, it read like a first novel, by a talented new author who's still refining her trade.

Coronovirus put paid to the usual Worldcon this year (CoNZealand 2020), which was hugely disappointing to me, as it was to be in Wellington, here in New Zealand. I had booked flights down, a hotel, membership of SFWA, etc. Instead, I watched it avidly online. The organisers did a good job providing a virtual con, and I enjoyed what we did get enormously. As mentioned in the original post on the Con, the chats between the likes of Silverberg, Martin, Dann and Haldeman were the highlights for me, and judging from the number of attendees to these online sessions, they were generally popular. One positive outcome to this was that it inspired me to seek out some of George R. R. Martin's earlier SF work. As a result I've read a number of his famous short stories, as well as made a start on the Wild Cards mosaic novels that he edited. Reading this earlier work has reminded me just what a fine writer he is. I became a bit frustrated with his Game of Thrones fantasy books, but his early SF is super - find it and read it if you can.

The Worldcon is the event in which the Hugo Awards are announced of course. They were notable this year, I felt, for two reasons. Firstly, George Martin, as toastmaster, came in for a heap of criticism for mispronouncing the names of some nominees. He was called a racist and other unpleasant things, which I felt was highly unfair. Admittedly, he pronounced several names wrong, but of various people from different nationalities and genders, and there was no suggestion to me he did anything other than make some honest mistakes. In all other ways, he was charming and entertaining as toastmaster - in contrast to the self-serving and highly ungracious speech made by Jeanette Ng which was a disgrace. But the Hugo's and their organisation have got a little lost, it seems to me, with 'diversity' and political correctness being taken to extremes these days. This brings me to the second issue I noticed regarding the Hugo's: the nominees seemed, more than ever, to offer diversity for the sake of it. If you are writing SF from one of the majority groups (e.g. male, white and straight), the message is clear - don't get your hopes up too high. If the nominee stories were all excellent (as they should be) this would be a non-issue - it shouldn't matter a jot to which background or group the authors affiliate of course. Except there are two inconsistencies here: firstly, the short story nominee authors were not actually a very diverse group, but a rather narrow group (predominantly LGBT women) which rather undermines the point of championing diversity; and secondly, the short stories themselves were simply not very good. I didn't rate any of them highly, and I'm quite sure none of them would have won a Hugo Award 10 years ago. This suggests to me they were nominated on the basis of the author, not the story. It's a shame, I think, as there is still good SF out there, but if your face isn't 'diverse' enough, your work seems less likely to achieve recognition in the current climate. I'm hoping this is a temporary trend, reflecting current social pressures and the laudable imperative to undo some of the misogynistic, male-oriented and predominantly white background of SF literature's past. Fairness to all, and genuine diversity, is of course a positive advance, and should be supported. But current efforts in this regard seem to have overshot what was required, and the end result smacks of minority "social-justice warriors" now running the show; it would be nice to see SF work lauded whatever the gender, race, and sexual persuasion - even if that means the author happens to be, for instance, white, male and straight. I live in hope.

Finally, I should note in reviewing the year that I've started to read a lot of old magazines, especially Analog (and now Asimov's) from the 1970's and 1980's. The quality of science fiction in these magazines was truly excellent, and I encourage all to find older issues of these magazines. I've recently re-subscribed to Analog and Asimov's and I'm hoping to get more enjoyment from the current issues in 2021. Reviews of stories and articles from these magazines will continue to appear here (under the magazine tab) over the coming year.

SHORT AUTHOR PROFILE 29 November 2020

Gordon R. Dickson

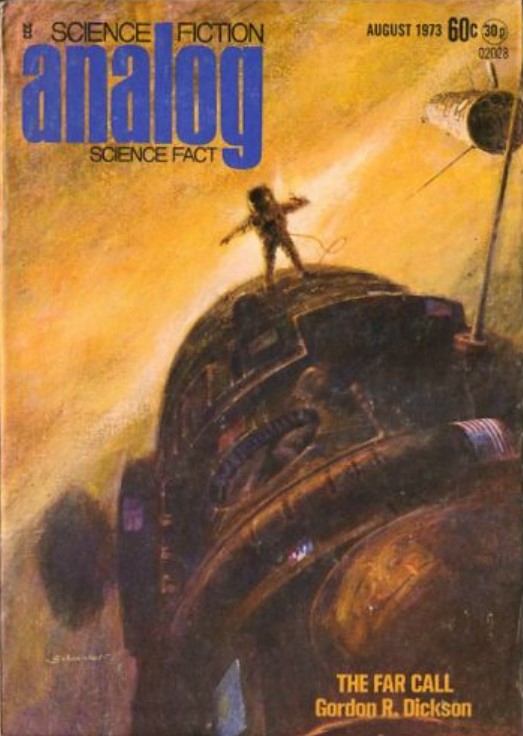

Gordon R. Dickson may be best known for his military SF novel Dorsai! (1976) and its numerous sequels that make up his Childe Cycle of novels. However, Dickson wrote an awful lot of other good SF. Born in Alberta, Canada in 1923, Dickson was inducted into the SF Hall of Fame in 2000, the year before his death. He collaborated a good deal with Poul Anderson (notably on their Hoka! books) and won 3 Hugo awards, and 1 Nebula. His Hugo awards were for the short story Soldier, Ask Not (1965), and in 1981 he won both the best novella category (for Last Dorsai) and best novelette (for The Cloak and the Staff). The Nebula award was won with his novelette, Call Him Lord (1967). Why bring Dickson up now? I just read a serial (novel) by this author that was published in Analog between August and October 1973, entitled The Far Call.

The Far Call is a terrific short novel, serialised in 1973 Analog, that was later expanded into a longer novel in 1978. This is great hard SF and if you like reading tales of realistic solar system exploration in the near future, you would enjoy this. The action is split almost 50:50 between Earth (Kennedy control and the political difficulties behind a manned-voyage to Mars), and the action on board two spaceships who are making the first Mars-bound trip. This story is as much about the way in which political pressures can adversely affect practical outcomes as it is about going to Mars. And yet, there is plenty of action to enjoy too. Due to an over-crowded experimental schedule, agreed to by political committee, the astronauts ('marsnauts') are over-worked and start to make minor mistakes. When disaster strikes, their problems are compounded. The serialised version of this story is I believe only available from Analog, but the expanded 1978 novel (well reviewed upon its publication) may be easier to find. Warmly recommended.

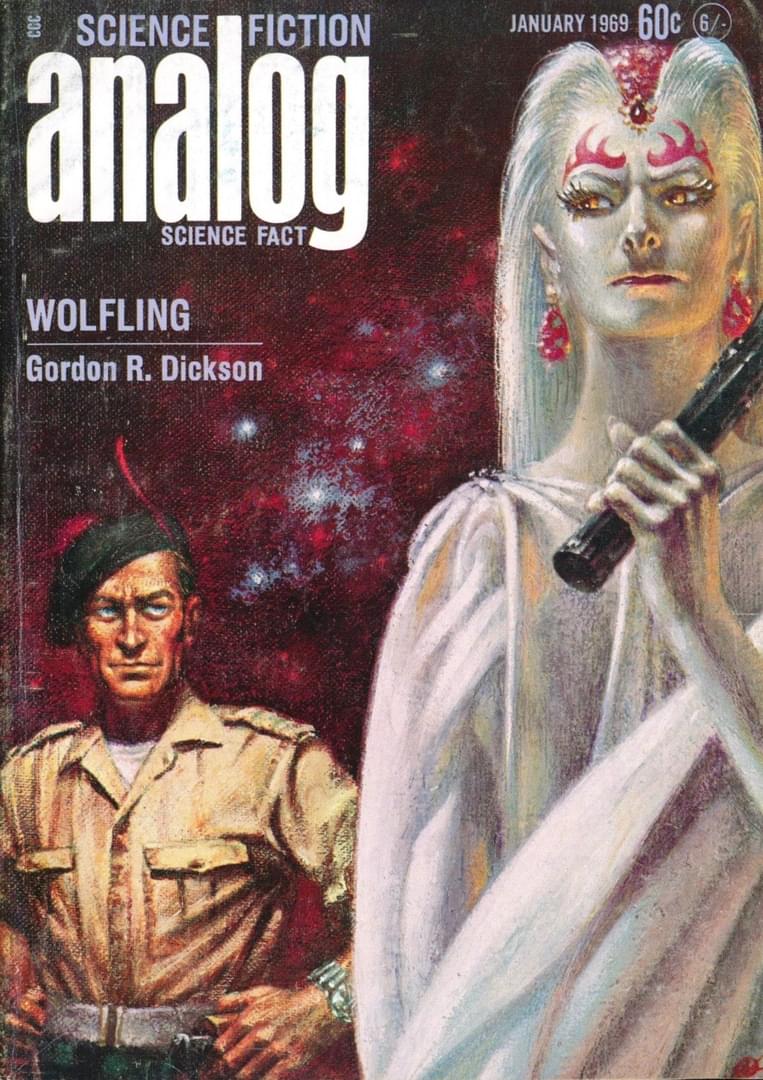

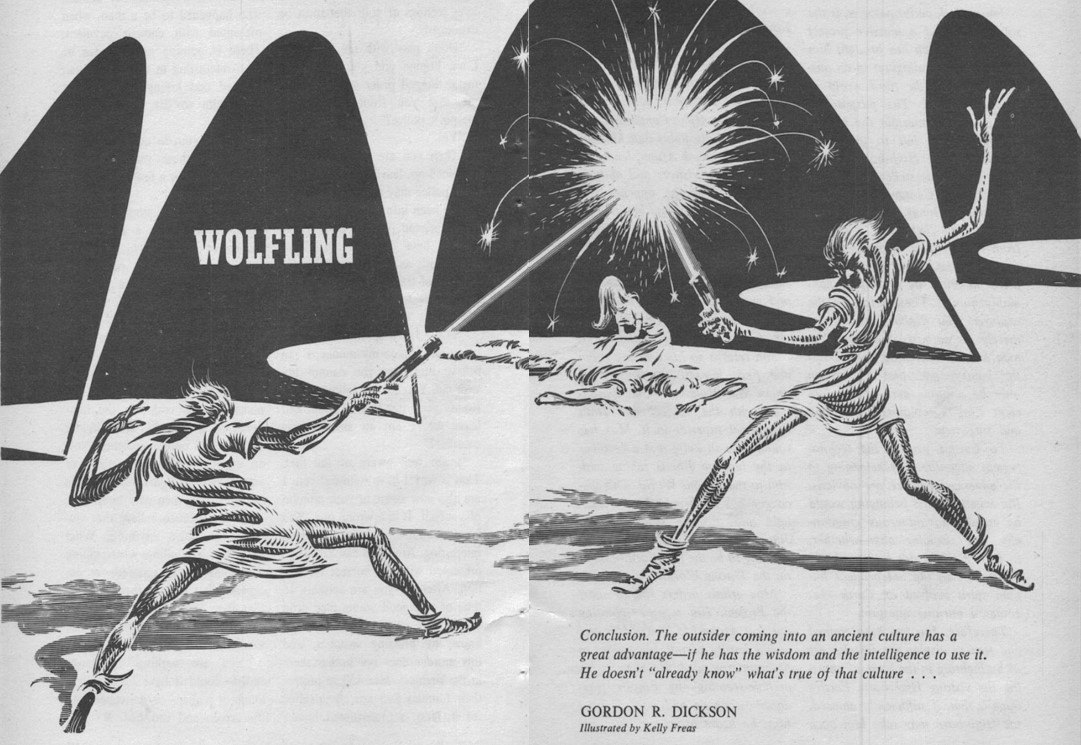

While on the subject of Gordon Dickson, it may be interesting to those who have not previously heard the suggestion, but he is believed to have 'invented' the idea of Star Wars' lightsabers! Whether George Lucas was aware of Dickson's novel Wolfling(1969) or not we cannot know for sure, but the description of an alien weapon called a 'rod' would be unerringly familiar to Star Wars fans. Wolfling was serialised in Analog in 1969 and illustrations on the cover of the January 1969 issue and in the March 1969 issue show the alien rod weapons (see below).

The artwork for Wolfling certainly looks as though it could have provided inspiration to a young George Lucus, who has commented that he read a good deal of SF in his younger days.

Other works by Dickson that I've read include Dorsai!, the first of the Childe Cycle novels. I read this a year or two ago and certainly enjoyed it and would recommend the book. The Child Cycle was an ambitious writing project, and was never completed. The series title is an allusion to "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came", the poem by Robert Browning and was conceived by Dickson as a long allegory of human evolution. Planned to extend from the 14th century through to the 24th century, the published novels only begin in the 21st century with Dorsai!

Artwork for Wolfling (Analog 1969)

SF NEWS 19 November 2020

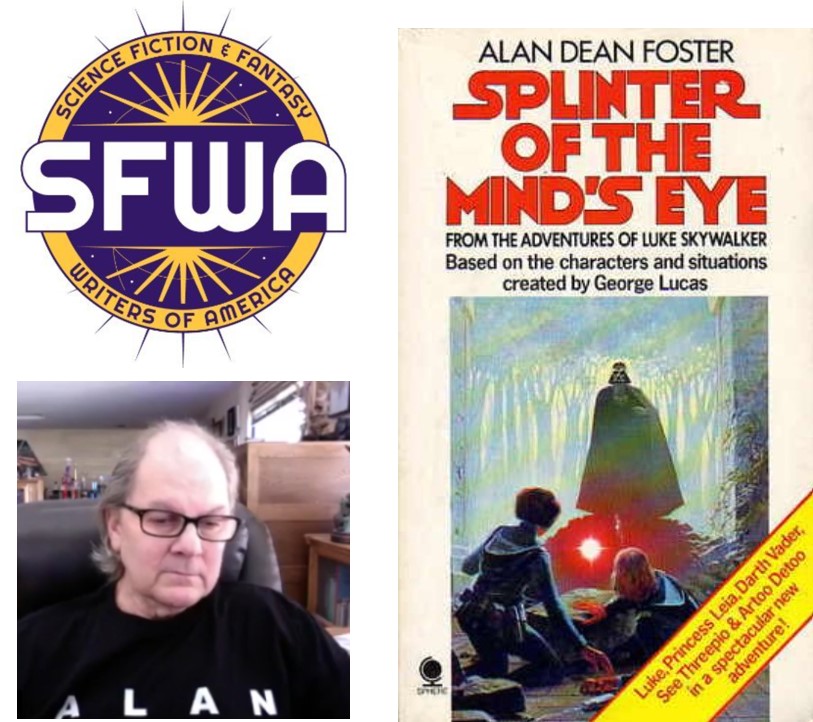

Disney Withholding Royalties from Alan Dean Foster

A news story outlining dreadful mistreatment of one of my favourite SF writers by a media giant has broken in the last day or so. It was revealed in a press conference held by SFWA President Mary Robinette Kowal, Alan Dean Foster and Foster's agent Vaughne Lee Hansen, that since acquiring the rights to both his old Star Wars novels and more recently his Alien novels, Disney have not been paying Alan royalties for his books. This is in apparently clear contravention of his royalty contract. Bizarrely, Disney claim they acquired the rights to the books, but not obligations to pay royalties. This sounds patently ridiculous of course. Alan has apparently been trying to raise this with Disney for a long time but has had, to date, no joy other than a recent offer to meet under an NDA, which would be highly unusual before any discussions have even started. Hopefully it will be resolved soon, and Disney will either pay the back-royalties and royalties going forward, or pay the back-royalties and hand the publishing rights back to Alan. In the meantime, I'll be avoiding Disney products where possible, and buying and reading Alan's non-Disney-owned books with increased fervour. As such, I ordered Alan's 2008 short story collection, Exceptions to Reality immediately after watching the press conference. The full announcement from SFWA, along with an opportunity to view the press conference can be found here . Thankfully, this issue has received a lot of coverage on the net, with articles on The Wertzone (where I first heard about it), Deep Dark Space, and in numerous twitter feeds from sympathetic fellow authors such as Cory Doctorow, John Scalzi, N. K. Jemisin and others, with the hashtag #DisneyMustPay. Hopefully all the media attention will force Disney's hand.

#DisneyMustPay

CURRENT READING 06 November 2020

Reading Through Analog Magazine, 1983

I'm currently reading through the issues of Analog Science Fiction & Fact from 1983. I have all these in paper copy, and from each one I'm selecting a single story, novelette or novella to read. The selection is based either on which story garnered the most awards historically, on personal preference of certain authors, or occasionally, entirely randomly. I've conducted the same exploration of Analog magazine issues from 1976 and 1979 also, recently. Reviews and comments from these old magazine readings can be found through the Magazines tab above in the menu, or for this current read through you can simply click

here.

I've found that reading a selection from each issue means you end up reading some of the less well known stories by famous and/or favourite authors, but it also 'requires' one to read stories by authors who were well regarded in the 70's and 80's but which have been largely forgotten, except by the most avid SF fans. From 1976, 1979 and 1983 Analog issues I've lately enjoyed stories by authors such as Hayford Pierce, Arsan Darney, P. J. Plauger, Michael McCollum, and Thomas Easton. These have all been to a large extent 'discoveries' for me.

APPRECIATION 29 October 2020

Fredric Brown & his novelette 'Arena'

Today marks the 114th anniversary of the birth of the 'Golden Age' SF writer Fredric Brown, perhaps best known for his novelette, Arena. I thought it might be nice to pay brief homage to the author and his famous story. Arena was published by John Campbell in the June 1944 issue of Astounding magazine. A human scout ship pilot, Carson, finds himself transported to an arena on an alien world by a god-like third party 'entity'. In this arena he must pit his wits, strength and resilience against a representative of the alien race with whom the humans are currently warring. The stakes are survival of either species, the loser of the personal combat dooming his race to oblivion. It's a cracker of a story. Coming before the advent of both the Nebula and Hugo Awards it didn't receive any gongs upon its publication, though it is widely regarded as one of the great, classic SF stories. It has been anthologised many times by the likes of Asimov, Aldiss, Conklin, and Silverberg (notably in the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology), and its been translated into at least 10 languages. Star Trek used the main plot idea in Episode 18 of Season 1 of the original series ("Arena", which first aired 19th January, 1967), in which Captain Kirk faced an alien (a 'Gorn' in the TV show) in similar circumstances of personal combat.

I've read several other Fredric Brown stories and I generally enjoy them, though none so much as Arena so far.

Fredric Brown seems to have been an interesting figure. By all accounts he didn't like writing much, and this may be why he became most well known for short fiction, publishing only five short SF novels between 1949 and 1961, but over 100 short SF stories between 1940 and 1967. Philip K. Dick was very complimentary of his 1945 short story The Waveries (Astounding Science Fiction, January 1945), and it has been anthologised to a similar degree as Arena. I've read The Waveries, and it's an excellent short story, about an invasion of earth by waveform 'aliens' that render electrical technology impossible, sending humanity back to a nineteenth century way of life. Likewise, The Star-Mouse (Planet Stories, Spring 1942), Pi in the Sky (Thrilling Wonder Stories, Winter 1945), and Sentry (Galaxy Science Fiction, February 1954) are other highly regarded stories worth seeking out. In total, six of Brown's short SF stories have been short-listed for Retro-Hugo awards in recent years. In addition to SF, Brown wrote a lot of detective and suspense fiction with considerable success. Happy birthday, Fredric! (Fredric Brown died in 1972 at the age of 67, but perhaps the powerful entity that arranged Carson's test in Arena will be able to pass on the birthday greetings somehow).

SHORT REVIEW 1 October 2020

The Reefs of Earth - R. A. Lafferty

I read the The Reefs of Earth in a couple of days. That indicates it's a quick read, which further suggests it's very readable. But as it's Lafferty, that only tells a small part of the story. I'm not sure what I think of it, which I expect is a common response from readers of this most eccentric of writers.

Its odd, I think I can say that without hesitation. I suppose its humorous, but in a surreal, wry way, not a chuckle-some way. It's about a family of Puca people (from another planet) who are living in the mid-west of America at an indeterminate time, who think nothing of killing 'Earthers', who they don't much like or respect. The children of this family (6 young children and one ghostie) run off from their parents and swan up and down small tributaries of the Missouri, communing with dead "Indians" (who they do like), and chatting about how they will kill everyone on Earth, without really getting on with it.

And that's about it. There is no real denouement and nothing that is set up at the start really comes to pass. People get chased, several get murdered, and the Puca sing there way through the events by way of four-line rhyming poems that are supposed to act as spells, but which never actually seem to do anything at all. In many ways, it's a load of old rubbish. And yet, I think I liked it. The language is kinda fun (it's written in a folksy manner that seems to place it in the past, though its set in modern times) and Lafferty trips you up constantly with non-sequiturs and strange observations that may or may not be wisdom.

One thing I can say, Lafferty is a true original. You would think SFF, by its nature a genre of imagination, would be replete with myriad true originals, but in fact there are only a few I think. They derive from and follow no-one else, they plow their own literary furrow and they have a signature style of writing that surely was never taught. I can only think of two authors who definitely fit this description: Lafferty and Cordwainer Smith, and you could perhaps include PKD as an honourable mention. We perhaps need to read the true originals now and then to remind us of the infinite scope of SFF writing, which can sometimes seem rather derivative.

REVIEW 28 September 2020

Wild Cards I - Edited by George R. R. Martin

Wild Cards is a long-running SF superhero series set in an alternative Earth, in which an alien "Wild Card" virus infected Manhattan in 1946, and then in time spread to other regions of the globe. Killing 90% of those who became infected, it turned a remaining 9% into "jokers" (who typically obtained hideous deformities, but few valuable powers) and only 1% into "aces" (the superheroes of this alternate universe). Its a terrific idea, based on a role-playing game George R. R. Martin invented and ran in the 1980's. The books either consist of connected short stories and novellas (such as this first volume), or 'mozaic' novels written by several returning authors who regularly contribute material. There are now 28 books in the series, and the reading order may be found here.

Wild Cards I starts the series and comprises stories set in chronological order, ranging from 1946 when the virus first hit Manhattan, to 1986 when this book was first published. I was very impressed with the strength of the material. Established stars of the SF field contributed stories as well as less well-known authors. Roger Zelazny contributed an excellent story about The Sleeper, Croyd Crenson, that I think would stand up on its own in an anthology of the year's best SF from 1986. Walter Jon Williams and Melinda Snodgrass also offer up very good stories that pit early aces up against McCarthyism with pathos and verisimilitude. By setting the stories of the jokers and aces against a backdrop of genuine history, amended here and there to suit the Wild Card universe, the set up enables stories to explore social ills and human foibles with admirable depth. These stories take us through the early Hollywood TV scene, the San Francisco-led counter-culture, Vietnam and the challenges for returning veterans, the New York nightclub scene (Mick Jagger chats with David Byrne in the CBGB club in the background to one story) and other landmarks of American history, including political machinations and Presidential elections.

Its interesting to me that I only recently became aware of this series, but I'm glad I did. There are few uses of superheroes in science fiction, funnily enough. Superhero fiction is mainly limited to comics from DC and Marvel and they have recently been swamping cinemas in movie format. The paucity of SF superhero literature perhaps stems from the idea that superhero powers are not very scientific, and also perhaps that superheroes target more of a youth or YA audience. Wild Cards seems to avoid these challenges by offering up a cohesive (if far fetched) scientific backstory as an explanation for the sudden appearance of aces and jokers, firmly classifying the books as science-fiction. They're also clearly aimed at adults; these are not YA, and I wouldn't recommend them to my teen. Graphic sexuality and violence are found here, though I don't feel it's ever gratuitous, its simply aimed at a mature audience.

Overall, I'd recommend Wild Cards I to SF fans who've not yet read it. The stories here are, more than anything else, entertaining and interesting. The real-world backdrop allows famous names to be dropped in and to make subtle changes to how history unfolds in interesting ways. The aces and jokers themselves have interesting abilities and the overall experience is engaging and satisfying. I'll be reading more in the Wild Cards universe, I'm sure.

REVIEW 19 September 2020

Saturn - Ben Bova

Bova's Grand Tour novels (see reading order

here) are hard-SF explorations of the solar system, with focus on the potential for life on or around other planets and moons, and used as a method by Bova to critique human foibles and the damage we have the potential to cause to these extra-terrestrial habitats. When done well the Grand Tour books are great and warmly recommended (e.g. Mars and to a slightly lesser extent Jupiter), but the books are a little uneven in quality, and this is not one of Bova's better Grand Tour novels, I think. In Saturn, a large rotating space station 'habitat' is making its way to Saturn from Earth for reasons of scientific exploration, housing 10,000 people who have volunteered to take the long journey there, due to dissatisfaction with (or expulsion from) Earth and its draconian laws, enforced by the 'New Morality'. The book principally involves the underhand methods of certain senior members of the crew who were placed there by the New Morality to gain power and influence in the new society aboard the habitat. The characters presented are rather thin, being either 'good' or 'evil'. The few that offer shades of grey (such as the stuntman Manny Gaeta) are more interesting, but they do not lift the book sufficiently for me. Ultimately, the book fails to deliver what the reader is really looking for in these books, as the action and plot is almost entirely associated with the political machinations of certain characters, and not to do with Saturn and its exploration. Indeed, we don't even reach Saturn until the end of the book, which should perhaps more accurately be titled "Journey to Saturn". This is in contrast to the book Jupiter, where the story takes place in orbit and within the atmosphere of the planet. This book is therefore probably for completists of the Grand Tour books; if you want to try the books, I wouldn't recommend starting with this one, but would rather suggest Mars or Jupiter which I feel are better paced and offer more interesting hard-SF stories.

SHORT REVIEW 15 September 2020

God Emperor of Didcot - Toby Frost

There actually isn't an awful lot of humorous SF out there. The yardstick by which humorous books get compared is inevitably The Hitch-Hiker's Guide the Galaxy, and that's perhaps unfair, but the choice of comparators is not great. Toby Frost's Space Captain Smith books actually stack up pretty well. This, the second book in the series, concerns the invasion of Urn by the evil Ghast Empire. This is a disaster, as Urn provides the British Space Empire with most of its tea, which as we all know, provides the Moral Fibre upon which the people of the Empire depend.

This is an overtly English book, aimed at the English and full of British in-jokes and cultural references. That's not to say it couldn't be appreciated by those outside Britain, but many jokes won't warm the heart of the non-British as they did for me. The jokes come thick and fast, but not at the expense of the characters and their development, and the plot is well paced and engaging. Rarely do I actually laugh out loud when reading, but this did have me spraying my tea in sudden amusement more than once. Ultimately, funny books will always struggle to offer the depth and resonance of more serious works, and this is indeed the case here. But it is nonetheless a wry, clever, and well-observed satire of the British (and their fascination with tea).

SHORT NOVELLA REVIEW 11 September 2020

The Queen of Air and Darkness - Poul Anderson

This novella, or

iginally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in April 1971, went on to win the Nebula Award for Best Novelette that year and both the Hugo Award for Best Novella and the Locus Award for Best Short Fiction in 1972. Quite how it won in different story length categories is a mystery (its a novella). What is not in doubt is its quality though. A woman hires a private detective, on the colony world of Roland, to find her young son who suddenly disappeared. The boy has been taken by the natives of the planet - the 'Outlings'; rumour and myth has been growing that these creatures are elvish or faerie creatures of celtic or norse mythology who live in the far north.

Sightings of Outlings have not been made in the main centres of human civilisation, but in the arctic border communities the rumours grow and gain strength. As the mother and the detective travel north, the truth behind the disappearance of human children and the nature of the Outlings becomes clearer. This is a good story, exploring the clash between cultures, between modern rationalism and natural mysticism. This cultural clash does not resolve to a single truth, rather it implies that different outlooks shape one's truth, without rendering other outlooks impossible. I liked the story very much, and by switching between the rational immigrant humans and the 'faerie' Outlings, Anderson gets to write successfully in both genre's at which he was a master, in the single story.

REVIEW 5 September 2020

The Eleventh Gate - Nancy Kress

The Eleventh Gate is a new space opera from the multi-award winning author Nancy Kress. I'd previously only read some of her short fiction, which I've been very impressed with. This novel follows the political and military fall-out that results from the discovery of a previously unidentified interstellar gate, leading away from the 10 inhabited worlds of humankind. Since the fall of Earth most people have either lived on Polyglot (a neutral, politically moderate world), on one of three worlds run by the Peregoy Corporation (a benevolent dictatorship) or on one of the three worlds run by the Landry Corporation (an extreme 'libertarian' meritocracy). Both the Peregoy and Landry systems are of course deeply flawed, though the Peregoy's seem have the moral high-ground in the main. How this all plays out was quite interesting, and the writing here is fresh and pacy. I enjoyed the characterisation, and Kress does a good job of presenting some characters as initially appealing, until we learn more and more of their moral failings and eventually learn to despise them, which provides a sense of growth to the story arc. Where the book was perhaps slightly less successful for me, was in the slightly simplistic sociopolitical ecosystems that are presented. It's difficult to clearly convey sociopolitical complexities in a SF novel where you also want to present and explain so much else (such as interstellar gates). But I struggled with the idea that whole planets (or collections of planets) could ever accept a unified culture. While the plot concerns rebellion against these unified cultures at the time of the book, they have been stably in place for 150 years by that time, which seemed a little hard to swallow. We have hundreds of languages, cultures, religions and political systems here on Earth - why when we get to new planets do we all buckle down to the same planet-wide beliefs? This is not a particularly pointed criticism of Kress' novel, as it is perennially a problem in SF, which often pitches planet A at war with planet B - I've only chosen to raise it here - but the issue did strike me as I read this book. On a positive note though,

some aspects of the novel, such as corporation-led government rather than nation states, and the use of biowarfare, rang true.

Interestingly, this book looks at the ramifications of losing connectivity between star systems. The same broad idea was also key to the plot of Scalzi's Interdependency Trilogy and its hard not to make a few comparisons between the books as a result. Scalzi's books are very smoothly written and accessible, but The Eleventh Gate was not less satisfying overall for being less punchy. In fact, in some ways, I liked this novel slightly better. I found Scalzi's construction of the Interdependency challenged credulity more than Kress' unified planet-wide cultures and I also marginally preferred Kress' characterisation, I think.

So, all-in-all, I'd recommend this, with minor reservations. It's a well-paced and engaging story, with good characterisation and a satisfying story arc. On the flip side, it won't win awards for startling originality, the sociopolitical construction did not entirely work for me, and the story doesn't exactly go where I thought it might, beyond the eleventh gate (it would be hard to say too much on that front without giving away spoilers). Finally it's worth noting, this reads as a complete story. Kress may conceivably write sequels to this book in due course, but they are not necessary, so if you are looking for a standalone 'military' space opera with some interesting ideas, this would be a worthwhile book to try.