Welcome to Starfarer Science Fiction, an amateur fan site for SF literature. Under the various links you can find bibliographies of certain authors, various 'feature articles' including award lists, a few personal lists of recommended reading, reading order of SF book series and other SF book trivia that I've compiled as part of my hobby and enthusiasm for the genre. I predominantly read the 'classics' of the genre, so information and reviews will tend to focus on well established and 'classic' authors. As a reviewer for Tangent Online, my reviews of current SF magazines can be found on the Tangent site, but summaries and links to the full reviews can be found if you hit the Magazines link.

SHORT REVIEW 31 December 2022

Lord of Light - Roger Zelazny

Lord of Light (1967) is a science fantasy novel and possibly the most well known (and possibly well regarded) work by the late Roger Zelazny. Calling it a science fantasy is not a stretch here, as Zelazny purposely wrote a novel that could be read as either SF or fantasy. In a far future, the vast majority of the colonists on an Earth-like world live in an undeveloped, almost medieval state, under the 'guidance', rule and tyranny of a pantheon of gods. These gods, having taken the names and appearance of the Hindu deities, are actually the original (and now immortal) human colonists who appropriated all the highest technology to elevate themselves above the common people. One such 'god', Sam, has the form and attributes of Siddhartha or Buddha, and he decides to fight back against the tyrannical Hindu gods in favour of the people.

The novel is certainly inventive, it's quite possibly well-researched with regards to Hindu religious belief and mythology (I'm not really in a position to comment on this aspect), and it comes across as very 'clever'. This cleverness is not really a positive, however; the cleverness is rather too strained, and it overshadows the narrative - if this were a film, one might say that you can see the wires.

The other major problem with this novel lies in its construction and pacing. It is so episodic, the chapters seem more like connected short stories than a satisfying single story arc. Occasionally exciting and well-paced, the book alternates these episodes with extended sections one can only describe as boring. This was not an easy or enjoyable read. Characterisation is thin, with no character development to speak of. The novel won the 1968 Hugo Award for Best Novel, but be warned, Lord of Light has not aged well, and reflects the excesses of the SF New Wave, popular at the time.

SHORT REVIEW 15 December 2022

The Reefs of Time & Crucible of Time - Jeffrey A. Carver

The two novels The Reefs of Time, and Crucible of Time, make up a duology Carver calls the Out of Time sequence. These books actually comprise the fifth and sixth books of his Chaos Chronicles that started with Neptune Crossing published in 1994, and which were reviewed here in March 2022. It took Carver a long time to finish and publish these books in 2019, with a decade coming between them and the preceding fourth novel, Sunborn. It was worth the wait, however - these are entertaining, contain many exciting passages, and continue Carver's highly imaginative explorations of multi-dimensional hard SF.

The two books are essentially one long, split, novel, in which our heroes from the prior books must travel to the planetary system of Karellia to try and shut down a planetary-defense system, which uses time shifts to avoid asteroid strikes. Unfortunately, this defense system has also introduced a time-shift element to the nearby galactic 'starstream' (an artificial 'n-space' highway), which is allowing the entry of a devastating AI enemy into our time from the distant past.

In theory, one could read these books and follow what was happening, as all the Chaos Chronicle stories standalone as separate adventures. However, Carver's multi-dimensional universe and the very strange aliens he invents would probably confuse readers who first dive into his books here. Moreover, he references earlier events from the first four books a awful lot. In short - these are very inventive and quite different from the usual space opera, and are recommended, but if you haven't read at least Neptune's Crossing, perhaps start there - but that book is a blast and highly recommended, so that's no hardship.

SHORT REVIEW 16 October 2022

Masterpieces: The Best Science Fiction of the Twentieth Century - Ed. Orson Scott Card

There are many 'best of' anthologies that aim to collect the finest short stories of the genre. Many have covered the golden age well and the Hall of Fame books, edited by Robert Silverberg, are semi official 'best of'' anthologies that collect many classic tales up until the start of the Hugo's (i.e. 1964). This volume, edited by Orson Scott Card, is attractive as it includes numerous classics missing from the Hall of Fame volumes, and secondly, because it covers three distinct eras: the golden age, the new wave, and the media generation.

The golden age section includes some great classic stories, including Poul Anderson's Call me Joe, and Robert Heinlein's All You Zombies—. The Heinlein is perhaps the great time travel paradox story, and a challenge to get your head around. Also in this section are a Theodore Sturgeon that I liked (A Saucer of Loneliness), which is unusual as I rarely like his work, and the great old Edmund Hamilton tale, Devolution.

The second section - the new wave - is perhaps the strongest, containing Harlan Ellison's "Repent Harlequin!", Said the Ticktockman, Robert Silverberg's Passengers, and Larry Niven's Inconstant Moon, all of which are five star stories. Silverberg's story particularly impresses and is highly recommended. Also in this section are other famous stories that have a lot of merit, though they are not perfect for me. Ursula Le Guin's The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas is thoughtful philosophy, but with no plot or characters is not actually a story and the R.A. Lafferty tale (Eurema's Dam) is typically surreal and quietly impressive, but he wrote many much better stories and is therefore an odd choice.

The media generation section contains a few very good stories. George R.R. Martin's Sandkings is superb (his short SF generally is), and the C.J. Cherryh story (Pots) is also a strong entry. However, it must be said that it was a strange choice - in a volume that aspires to gather the finest SF from the entire century - to include six stories from 1985. One gets the impression Card had simply read a lot of work in '85, and selected from that. This odd bias toward the mid-80's lets the volume down rather, given what could have been selected from the hundred years on offer.

REVIEW 10 August 2022

First Lensman - E.E. 'Doc' Smith

First Lensman (1950) is the second volume, by internal chronology, of Edward E. Smith's classic 'Lensman Series', though it was the final volume to be written. Between 1937 and 1947, Smith originally serialised in Astounding what became four books in the series, starting with Galactic Patrol. In 1948 he reworked Triplanatery (which was first serialised in the magazine in 1934 as a standalone novel) as a prequel, and then wrote this second novel to act as a bridge between Triplanatery with the original Lensman stories.

Triplanetary (reviewed below, on 25th December 2021) was very episodic, and certainly came across as a reworked and expanded earlier novel. While it introduced some background to the galactic politics between two ancient and powerful races, it did not introduce the 'lens' apparatus or its wearers. First Lensman is in contrast a much more cohesive book, and is relatively well structured. It's certainly a better book, and more readable. Virgil Samms, one of the heroes of Triplanetary, is encouraged telepathically to visit the planet Arisia, home to the great, ancient and benevolent Arisians. There, he receives a 'lens' - a bracelet that confers telepathic abilities, and which can only be worn by the individual who meets the requirements to have one. Samms therefore becomes the first 'Lensman' and he goes on the select others who meet the requirements for lensmanship, who then each also acquire a lens. The novel then follows the Lensmen setting up a 'Galactic Patrol', to make the galaxy safe from wrongdoers of all kinds. In this volume, the target of the Lensmen and their new Patrol is a drug-smuggling operation of interstellar scale, run in part by an Earth-based politician.

So, is First Lensman much good? Well, its very old, and while it was written in 1950, it was written to fit into a space opera conceived in 1937, by an author who wrote much of their work in the 20's and 30's. It therefore unavoidably falls down in several aspects, though one must make allowances for the era it comes from. It has often been noted that Smith's work is very male-centric, though in fact, capable women are certainly not absent here. A failing of much old SF is that it plays fast and loose with physics; but again, this is not such a failing here as I would have expected. Smith tries where he can to follow natural laws. In space-ships everyone is weightless, so he gets one over on Star Trek and Star Wars in this regard.

There is also a good deal of clever invention here. One might expect lots of daft 'handwavium', but more often than not Smith comes up with intriguing solutions to physical problems. How could an alien species live on very cold planets, such as Pluto? Smith suggests they partially exist in hyperdimensions as well as the three we see, which effects their energy use and requirements. Indeed, his invention of aliens is really pretty good. The least reasonable aspects of the plot are not his aliens, or high technology inventions, its the (almost absurd) degree of efficiency with which the Lensmen and their allies can fulfill projects. I suspect this stems from the belief that we will become very efficient as we gain new technological insights, and this doubtless reflects an optimism typical of SF of this era, which seems strange now. As an example, in what seems like only a few months, the Lensmen identify a empty planet, recruit many thousands of skilled workers to move there and set up factories, and then build 6 (six!) superdreadnought space-ships, and a fleet of smaller craft. Despite the simple issue of manufacturing impossibility, where did they get the money to do it? Paying for stuff is not a problem the Lensmen have to consider it seems. However, such unbelievable productivity is probably the single greatest weakness of the book, which is otherwise an exciting and entertaining romp, and one of the founding pillars of the space-opera subgenre.

SHORT REVIEW 25 June 2022

1632 Series Books - Eric Flint

Update 20 July 2022: Within a few weeks of posting this short review, Eric Flint (Feb 6, 1947 - Jul 17, 2022) sadly died, at the age of 75, in East Chicago, Indiana. An obituary can be read at the Locus site, here. It is a real shame that there will be no further books penned by this most interesting of authors.

In the world of the alternate-history SF genre, several names currently stand out as prominent authors in the field, including Larry Turtledove, S.M. Sterling and Eric Flint. Of these, I've only read works by Flint from his most famous contribution to the field: the '1632' or 'Ring of Fire' series. As I have very recently finished one of these, 1636: The Saxon Uprising, I thought I'd provide a brief review the 6 books I've now read in the series.

1632 starts the series off with a cosmic accident that switches a sphere of the earth, containing the West Virginian town of Grantville in the year 2000, with (presumably) a same sized sphere of central Germany in the year 1631. The series then follows the realisation, exploration, survival and integration of the 'uptimers' from modern America, into central Europe during the 30 years war. It's a lot of fun, very well researched, and quite educational regarding Europe of that time. I've learned a huge amount about Gustav II Adolf, the Swedish king, and other key figures of the time from these books.

1633 and 1634: The Baltic War are a pair that need to be read one after another, and these were co-written by Flint and David Weber. Having found some semblance of order and integration in 17th century Germany, the uptimers find that their new-found allies are under threat from France (Cardinal Richelieu) and Denmark. The books are full of action, and although they are very long, they clip along at a good pace. In these books the uptimers progress from local defensive actions to generate armies and a navy. Parts of the novels take place in England, with a good side plot involving capture and escape from the Tower of London. Here, some of the uptimers encounter Oliver Cromwell - in the years before the English Civil war.

1635: A Parcel of Rogues is not one of the main story arc novels penned by Flint, but one of the many side-bar novels that focus on only a few characters. Here, we follow those who escaped from the Tower of London, including Cromwell and an uptimer sharpshooter on the run, and their adventures in Scotland. It's a lot of fun, and again, provides some history tuition along the way on England and Scotland.

1635: The Eastern Front and 1636: The Saxon Uprising are another novel pair that contain a single main plot development (and really need to be read one after the other). 1635: The Eastern Front is mainly concerned with the war of the new United States of Europe (under the new Emperor Gustav Adolf) with Poland, while 1636: The Saxon Uprising follows the resolution of a civil war that springs up as an indirect result of the Polish conflict. Both are entertaining, but the political complexity of the situation the uptimers have helped bring about make for a lot of explanatory dialogue, and the reader needs to pay attention to keep in mind all the vast cast of characters. These two books are 'mainline' novels that follow the big political maneuvers and wars between countries. Once read, they provide a fantastically rich background against which many 'side-bar' novels take place. I'm looking forward to trying some of these in due course, as I suspect they'll be a little easier to follow, and sound like a lot of fun.

For the full current list of books in the series, along with a suggested reading order click here.

REVIEW & AUTHOR FEATURE 21 March 2022

The Chaos Chronicles - Jeffrey A. Carver

Jeffrey A. Carver is perhaps most well known for his ongoing SF series, The Chaos Chronicles. Currently standing at six books - with a final seventh book currently being written to conclude the adventure - Carver started publishing these books in 1994 with the novel Neptune Crossing, which, like the next 3 sequels, was published by Tor. The first three books, which I just read in signed hardback versions bought directly from the author, were published in rapid succession in the mid 1990's.

Neptune Crossing (1994) is a fun, hard SF novel, set almost entirely on Triton, Neptune's largest moon, and follows the adventures of an ex-pilot, John Bandicut, who finds an alien artifact on a survey run. The nature of the alien 'quarx' that he encounters is inventive and the interactions between them work well. The alien is a dimensionally 'fractal' entity and once encountered, it lives within Bandicut's mind. Once there the quarx alerts Bandicut to an upcoming crisis for humanity, and Bandicut must take steps to try and stave off disaster. The conversational exchanges between the main character and the alien are entertaining and the story cracks along at a good pace.

This is hard SF in a sense, but some of the scientific extrapolations are so far advanced as ideas that the sub-genre is not so simple to categorize. In many ways, this book (and the series generally) strives for that 'sense of wonder' that was prevalent in the extreme speculations of the golden age (or maybe the '60's). More than once, I thought that the authors' works that came most readily to mind as comparators were Arthur C. Clarke and Larry Niven - both hard SF stalwarts, but both interested in exploring extremely advanced technologies in their speculations.

Strange Attractors (1995) takes off directly after Neptune Crossing, and follows Bandicut after he is 'translated' to a strange and enormous construction outside the milky-way galaxy: 'shipworld'. Bandicut joins up with several aliens there who have also been translated from their own star systems for reasons none of them understand. Shipworld is suffering from physical attacks from a fractal 'demon' entity (which the heroes call a 'boojum') that is disintegrating aspects of the world, and threatening millions. The ideas in this book take a quantum leap up in strangeness compared to the first book.

Indeed, Strange Attractors gives a hint to its contents with its title. It’s a book in the grand tradition of slightly trippy SF wherein there’s a genuine effort to describe a universe that’s stranger and more exotic that one might otherwise imagine, like a 1995 version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, or a more advanced sort of 'golden age' book that reaches for a bizarre sense of wonder. This is the kind of SF that is very hard to get 'right', but Carver's efforts are sincere and thoughtful and he makes a decent fist of a tough subject and ‘world’. Not enough SF really challenges our expectations or our understanding of the universe, and it was great to read SF that is really different to most of the derivative stuff out there.

The Infinite Sea (1996) follows the same band of heroes (now composed of Bandicut, Ik, Li-Jared and Antares) as they are catapulted along a star-stream conduit back to their galaxy by shipworld. Unfortunately, they find themselves transported within their star-stream bubble somewhere underwater and sinking fast, on another alien planet. At first, this novel strikes the reader as a strange diversion from the main story arc that Carver was drawing in the first two books. However, over time the story makes more and more sense, and by the end, the grander underlying story arc has been well-developed, leaving the reader wanting to learn more of the bigger picture.

Carver is good at building character and inter-relationships, and cleverly avoids the communication difficulties between aliens that might otherwise stultify the reading experience by his invention of 'translator stones' that are a unifying feature of the main characters. This was a good volume in the series - set almost entirely underwater - and sets up the idea of a grand conflict between two distinct 'master races' in the galaxy.

Fans had to wait until 2008 for the fourth book (Sunborn), and the fifth and sixth volumes (comprising the duology The Reefs of Time & Crucible of Time) were only recently published in 2019. Carver has admitted he's a pretty slow writer, but there is a thoughtfulness and skill in his books' construction and plotting, which defends the time he takes. One effect of the long wait between volumes was that, while Sunborn was still taken by Tor, the recent duology arrived after various changes at the publisher and Carver ultimately chose to self-publish them. It seems a slight shame that such good SF, offering a welcome change from the military space opera crowd, had to be self-published. I have all three of the other published books in the series, and will certainly be reading them shortly.

The Chaos Chronicles are not Carver's only SF output of course. He has penned many other successful novels, notably including the six-volume Star Rigger universe series, and well regarded standalone novels such as The Rapture Effect. The sixth volume of the Sar Rigger series, Eternity's End was nominated for the 2002 Nebula Award for best novel. I have not read these books yet, but look forward to trying them. His bibliography can be found here, and his own blog is entertaining and worth a read.

AUTHOR RECOMMENDATION 19 February 2022

Two Short Fiction Authors to Look Out For

In fairly wide reading of SFF short fiction, as a reviewer for Tangent Online, I come across many authors who are relatively new to the field or who may be unfamiliar to many readers. Over the past few years many authors have stood out as providing solid work, but two have made a particularly strong impression for the consistency of their output: Marie Vibbert and Brenda Kalt. Neither of these authors is especially new to the scene, as both have published numerous short stories since about 2014, but they are probably not household names. However, both seem to have really hit their stride over the last few years, and I've found that whenever I've read work by either author recently, the stories have been well-crafted and enjoyable. Both are published fairly often in Analog, so if you pick up a copy of the magazine and their work is in it, do yourself a favour and be sure to read it.

MINI REVIEW 17 February 2022

The Devil's Eye - Jack McDevitt

As one might expect from McDevitt, The Devil's Eye is very readable and entertaining. As one might not expect from the fourth in the Alex Benedict series, it's that this is not an archeology investigation, but almost a space opera on a grander scale. The characterisation is good however, and the reader is felt wanting to revisit Chase and Alex; though this may be in part because we'd like to see them back discovering lost spaceships! It's recommended, but it's not the finest in the series.

SHORT REVIEW 7 February 2022

Under a Graveyard Sky - John Ringo

This is the first in Ringo's ongoing ‘zombie’ SF series Black Tide Rising, which is now up to 10 books, including short story collections and contributions from other authors. In this series, the zombie apocalypse is mediated by a rapidly spreading new virus that is airborne in its initial flu-like stage, and then morphs into a blood-borne rabies-like neurological virus. One family of far-right survivalists take to the seas to survive the spreading pandemic. I can see the appeal here in a sense and I did finish the book. Ringo is clearly a professional artisan who knows how to keep the pace up, meet the shallower side of reader expectations, and provide a fun holiday read. It has moments of good tension, is written at break neck pace, and is underpinned by a reasonably novel scientific premise.

That being said, this is not a book that I regard highly or particularly enjoyed, looking back on it; there are too many serious problems. Firstly it should be pointed out that it is the start of the series story arc, and just stops at the end with the words “to be continued”. Just because this is book one in a continuing series doesn’t preclude a satisfying conclusion to this episode, and I found this annoying. The other significant issues I have with it are concerned with the ‘message' or perspective Ringo supplies, and the fact that much that occurs is frankly ridiculous.

The characters (who are neither very appealing or well developed) speak in militaristic jargon throughout, not only to provide some verisimilitude but mostly, it seemed, to bring a sort of 'military cool' to the violent events. The 'zombies' in the book are actually infected, living humans, and yet Ringo delights in having the 13 year old daughter of the protagonist shoot, stab, butcher and bludgeon these infected people in their hundreds.

The fact that the books killing machine is a 13 year old girl was not only silly and also somehow unsavory. Moreover, this 13 year old is described as a ‘hottie’; adult characters ‘joke’ that as soon as she’s ‘legal’ they’ll marry her, even going so far as to suggest that marriage would be legal at 14 in some States. To be fair, the adult's suggestion in this case does not come across as sexually motivated - it's her killing ability that attracts him - but the exchange gives a good sense of what's on offer here.

Throughout the reading I developed an increasingly uncomfortable feeling about the action scenes (which are very repetitive and ultimately lose their impact), and the found the dialogue to be ultimately rather unsavory and voyeuristic; Ringo seems to have created a ‘cool’ scenario that allows (in fact requires) extreme violence and extreme perspectives to flourish. The Black Tide Rising series is extremely popular, and I imagine this would appeal to many, but for those looking for humanity, three-dimensional characters or some subtlety in their SF, I wouldn’t particularly recommend it.

MINI REVIEW 12 January 2022

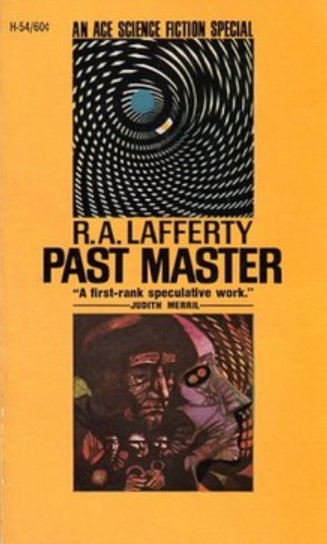

Past Master - R. A. Lafferty

Past Master by R. A. Lafferty is surreal - in a genuine way - and deep, and full of interesting thoughts and theses. It is mostly allegory, I think, and the use of Thomas More (the 16th century English lawyer, philosopher and statesman, who wrote Utopia) to explore the place of theology in culture is rather good. I wouldn't be so presumptive as to suggest I understood everything Lafferty meant in this work, but I got enough from the book to enjoy the reading experience. The central theme of technological progress leading to cultural collapse is one that appeals to me as a notion, as I share some of his apparent reservations. The character names are universally terrific, and the way Lafferty more or less ignores the passage of time gives it a very dreamlike feeling. It struck me the style of this novel has some similarities with Kafka (and perhaps Joyce), sharing some of the same surreal assumptions and other-worldliness.

This wont be for everyone, I think its fair to say, but is recommended if you are looking for something more literary from a unique voice in the field. Originally released in 1968, this novel was nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula awards, though it won neither. It has been noted elsewhere that the world was not really ready for Lafferty's genius. His books can be hard to find, although Past Master was recently collected the the Library of America's anthology American Science Fiction: Four Classic Novels 1968-1969, edited by Gary K. Wolfe.

For earlier years' articles hit the relevant archive button below

2021 Article Archive 2020 Article Archive