Welcome to Starfarer Science Fiction, an amateur fan site for SF literature. Under the various links you can find bibliographies of certain authors, various 'feature articles' including award lists, a few personal lists of recommended reading, reading order of SF book series and other SF book trivia that I've compiled as part of my hobby and enthusiasm for the genre. I predominantly read the 'classics' of the genre, so information and reviews will tend to focus on well established and 'classic' authors. As a reviewer for Tangent Online, my reviews of current SF magazines can be found on the Tangent site, but summaries and links to the full reviews can be found if you hit the Magazines link.

REVIEW 25 December 2021

Triplanetary - E. E. 'Doc' Smith

It's more or less fair to claim that E. E. 'doc' Smith invented 'space opera' with the Lensman series, and for all its faults it is an historically important SF series. In late 1936, Smith worked up an outline for 4 complete serials that would become the original Lensman story arc. All were serialised in Astounding Science Fiction by John W. Campbell, under the titles Galactic Patrol (serialised 1937), Grey Lensman (1939), Second Stage Lensmen (1941) and Children of the Lens (1947). These were hugely popular and successful, and Smith was provided the opportunity to republish the serials as novels in the fifties. He conceived the idea of expanding the series in 1948, reworking a hitherto unconnected serial Triplanetary (serialised in Amazing Stories in 1934) as a prequel. To do this he expanded the original serial, changed the names of various protagonists, and shoehorned in the alien races that feature in the Lensman books. However, this alone didn't bring the story up to the start of Galactic Patrol, so he wrote a second prequel, First Lensman, in 1950 to bridge the gap.

I thought it might be fun (and/or educational) to read through the series. Triplanetary was very interesting to read, and certainly not hard going though it creaks a little with age. It's hard to sum it up, as it is simultaneously two different things, depending on perspective and sentiment, and one's willingness to overlook it's age, and the imperfections of the time in which it was written. It is both:

(i) An energetic, classic space opera with big ideas

It has a naïve positivity and exuberance about it that charms for much of the time. The language and attitudes shown are like a history lesson in how things were seen, and while the young woman in the main story is given less to do than the heroic menfolk, she is not without agency. It's also a lot of fun to see the invention of ideas for the first time that were subsequently used by others in more recent SF. Notably, there are many elements that were clearly used by George Lucas, who is said to have been a fan of the books. Here we see a Death Star, effectively, though instead of containing Darth Vadar, it houses... wait for it... Roger! Heinlein was also on record as saying that no one influenced him more than Smith and he loved his work. So, if you're happy to go along for the ride and not worry over pesky details, it's an entertainment that will provide a good example of classic pre-Golden Age fiction.

(ii) Dreadful

And I mean that in the nicest possible way. It's badly written and chock full of plot developments that are ludicrous. The reverse engineering of extraordinary alien technology by humans in days (or even hours) is perhaps the most ludicrous thing about it, but there are many things one could pick apart. There's also not a clean plot arc here - it's really disjointed; unsurprising given Triplanetary was a mash-up of a 1934 serial that had nothing to do with the Lensman series and some 1948 material tacked on the beginning. The tacked on prologues don't really work or help, and the refit of the 1934 serial is clumsy, as it tries to shoehorn Lensman alien races and war into a story they don't easily fit.

This is a longish-term read through, and I'll be revisiting The Lensman series, with First Lensman in due course.

MINI REVIEWS 24 December 2021

Two New SF Short Story Anthologies

I recently read two short story anthologies that I mighty not normally have picked out to read, in order to review them for Tangent Online. Both were of course mixed in quality, but both included almost entirely new fiction and several stories in each were very good.

L. Ron Hubbard's Writers of the Future #37, edited by David Farland was quite enjoyable - in fact some of the stories are really rather good. With anthologies like this where there is no central theme, the concepts, prose styles and genres flit all over the place, and this anthology of 15 new stories includes SF, fantasy and horror. If you want to try new fiction by some new writers on the scene, it's of a quality that probably exceeds the average in the monthly magazines, but it rather lacks focus. This series has been published each year since 1985, with Algis Budrys editing about half the books. The best stories in this volume were Sixers by Barbara Lund, The Enfield Report by Christopher Bowthorpe, Half-Breed by Brittany Rainsdon, The Redemption of Brother Adalam by K. D. Julicher and The Skin of My Mother by Erik Lynd.

Gunfight on Europa Station, edited by David Boop (Baen Books) offered a more consistent quality of story. Essentially this is an enjoyable hard SF anthology, with most stories having some flavor or trope common also to the western genre, but it's not nearly as 'wild-west' oriented as the cover would suggest and titling the book “Frontier SF” would have been quite as accurate. The best stories are Hydration by Alan Dean Foster, Winner Takes All by Alex Shvartsman, Last Stand on Europa Station A by David Boop and Doc Holliday 2.0 by Wil McCarthy. For fans of hard SF who enjoy tales that focus on entertainment over those that present current socio-political points, this anthology should satisfy.

AUTHOR FOCUS 12 December 2021

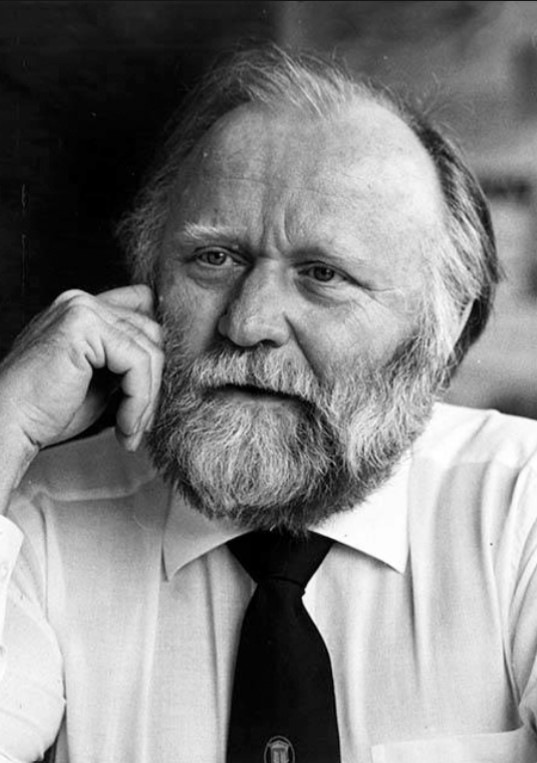

Frank Herbert and the Dune series

The author Frank Herbert has been added to the list of authors covered on this site, with a bibliography of his novels to be found here. Frank Herbert has become synonymous with the Dune series of books, though of course he wrote much more than these novels over a long and distinguished SF career. However, the Dune books are his best work, and the titular first novel in the sequence is commonly regarded as being the single greatest novel in the genre.

Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. (1920–1986) published his first SF short story (Looking for Something?) in Startling Stories in April 1952. A further half dozen or so short stories followed in the pulps before his first novel publication in 1956, Under Pressure, which was serialised in Astounding the prior year. He is known to have started planning Dune as early as 1959, though it did not begin to be published until 1963, when Astounding serialised Dune World - the first section of what would become the full 1965 novel. The 1963 serialisation came fourth in the 1964 Hugo Awards, but the novel scooped both the Hugo and Nebula Awards and in both 1975 and 1987 was named by Locus as the best SF novel of all time.

Having read the full Dune series in the 1980's and more recently having re-read Dune itself, I decided it would be good to revisit the sequels. To do this I decided to acquire hardbacks of the books in fine first editions, where possible. I've been able to obtain first editions of the five sequels (book club edition of Dune Messiah). I opted for the 1990 Putnam HB of Dune, as this edition matches the style of the other first editions released by Putnam well. My current collection of Dune books is shown below.

My re-read of Dune a couple of years ago reminded me how great it was - the world-building is extraordinary, and the depth of invention and wealth of novel ideas sets it apart from all but the very best SF. I re-read Dune Messiah and Children of Dune within the last month, and I'll read the remaining books shortly.

Dune Messiah is a much shorter book than Dune, and acts as a bridge between the adventure of Dune and the intrigue and excitement of Children of Dune. While shorter, it is quite a dense book, full of philosophical ideas. It conveys the complexities and subtleties inherent in the loss or abuse of power, and successfully rounds out Paul's time as Emperor. It is not without exciting passages, either, making it much more readable than some suggest.

Children of Dune carries on the philosophies, court intrigue and ambiguities introduced in Dune Messiah, but has a larger, more exciting overall plot. Paul's children, Leto II and Ghanima, are 'pre-born' with the memories of millennia of ancestors, and there are numerous plots to remove or subjugate them, in order to return Imperial power from House Atreides to House Corrino. Herbert ramps up the SF in a very inventive way, and the book's final sections especially, are top notch - maintaining philosophical depth as well as providing some terrific imagery and action.

God Emperor of Dune (note added following a re-read in January 2022) is very good. Set 3500 years after the events of the original trilogy, at a time when Leto II is the God Emperor, well on the way to fully metamorphosing into a human-sandworm hybrid. The philosophy that fill these books is certainly here, as in the previous two books, but it's interspersed with plenty of action, and the dialogue between characters crackles with energy. The sacrifice made by the God Emperor for the long-term benefit of an unappreciative humanity is full of pathos and is well handled. This book has a reputation for being a harder read than the previous books, but I enjoyed it quite as much as Messiah and Children, and it's recommended for those who read the first three but had not read further.

BOOK SERIES REVIEW 30 October 2021

Isaac Asimov - Elijah Bayley Robot Stories

Asimov started his robot stories in short form, chronicling the development of robots and their three laws with numerous stories involving the great early roboticist, Susan Calvin. These were largely written in the 1940's. But when he finally came to explore his three laws of robotics in novel format from the mid-1950's onward, he introduced the human detective character, Elijah Bayley. His colleague in all these stories was the 'humaniform' robot R. Daneel Olivaw. I recently re-read all 4 stories in which Bayley is the principal protagonist and offer a few reflections here.

The Caves of Steel(novel, 1954) is set a few thousand years into the future, and introduces the readers to Elijah Bayley. The detective, like all humans on Earth lives in a completely enclosed, largely underground, New York, afraid to go outside. He is asked to investigate the death of a 'spacer' at the space-town outside the city, and receives help from the humaniform robot Daneel to solve the seemingly impossible case. The novel is a classic of the genre, conveying well the claustrophobia of a future in which humans restrict their experience of the world. Asimov's skill at mystery plotting, and ingenious use of the 'three laws' of robotics add to the readability and enjoyment.

The Naked Sun (novel, 1956) sees Bayley leave Earth (the first Earthman to do so for hundreds of years) to travel to the spacer world of Solaria to try and solve the riddle of another mysterious murder. The world of Solaria - in which very few inhabitants live in isolation, shunning direct contact with other humans, and tended by thousands of robots each - is a fascinating construction, and allows Asimov to weave another intriguing plot. If anything, this is even superior to The Caves of Steel, as Asimov explores human contact and motivation in a fresh way, extending his range from his earlier work.

Mirror Image (short story, 1972) is the only short piece of fiction starring Elijah and Daneel. Asimov had been pressured for years to write further robot stories involving these characters and ultimately published this in Analog, sixteen years after The Naked Sun. Daneel comes to Earth to ask for Bayley's help in solving a problem between two mathematician passengers on a spaceship, each of whom claim to have had the exact same mathematical discovery at the same time. It's a terrific short story, and the prodigious intellect of Asimov is readily apparent.

Robots of Dawn (novel, 1983) is the third and final novel in which Elijah Bayley stars. Asimov recalls that, when he finally provided a further Elijah/Daneel story in 1972 with Mirror Image, he received lots of letters, essentially saying "thanks, but we meant a novel!". It took a further nine years for him to publish what his fans were after, but it was worth the wait. The first thing one notices when picking up The Robots of Dawn, is that its more than twice the length of the earlier novels, and at times it does seem a touch padded and bloated. The length was in response to his publishers request to meet more modern expectations, apparently. The second thing of note, is that Asimov has written a story where sex is front and centre to the plot, and accordingly is discussed on many occasions. Asimov was criticized at times regarding his earlier work for the paucity of strong female characters and lack of attention to adult themes such as sex. Clearly he thought, "I'll show 'em"! In this novel, Elijah travels to the planet Aurora, to try and solve the case of the 'death' of the 'humaniform' robot, Jander. He's again aided by Daneel, meets Gladia once more (the female lead character from The Naked Sun), and we are introduced to the interesting new robot character, Giskard. Asimov's attempts to explore sexual mores are laudable and partially successful, though addressing these sort of themes are not a strong suit of his. His strength lies in logical and immersive plots, and while their are some scenes that come across as padding, the final scenes are highly successful.

Interestingly, Asimov clearly had it in mind to link the robot stories with the Empire novels and Foundation books by the time he wrote The Robots of Dawn. He references the idea of 'psychohistory' in the book (invented by the robotocist Fastolfe) and sets up the development of a human Empire. There was a further novel that linked the series even more tightly: Robots and Empire (1985), set a few hundred years after Elijah Bayley's death. It's a decent novel, and further involves both Daneel and Giskard, and references Elijah Bayley many times, though he does not feature as a contemporary character of course.

MINI AUTHOR PROFILE 7 October 2021

Stanley Mullen

Fool Killer was published in Astounding Science Fiction in May 1958, and I read it as part of my read-through of the magazine issues in that year. Having started as a fairly typical SF story off-world, it turns into a classic of SF drama and speculation. A computer decides the right justice for an innocent man who's life was ruined when he was wrongly punished for committing murder. It's deemed fair that, as he paid the price for a murder he didn't commit, he now gets one 'free murder' he can commit without penalty. The inventive premise and the exploration of ideas here, presented through SF, is excellent and I think this a classic SF story, though I'd not heard of it before I came across it.

Stanley Mullen was born in 1911 in Colorado Springs and died at a relatively young age in 1974. In addition to his artwork and his publication of the fanzine The Gorgon, Mullen was principally known for his short stories, which saw print between 1947 and 1959. John Campbell published four stories by Mullen in Astounding, one in 1957 and 3 more in 1958. He never won a Hugo or Nebula Award, though he was a finalist for the 1959 Hugo for his short story, Space to Swing a Cat. His sole novel was Kinsmen of the Dragon, published in 1951. All of which suggests he was a minor name in SF, and it's undoubtedly the case that he is largely forgotten. So why the short feature? I recently read a short story of Mullen's and was extremely impressed and would go so far as to suggest it should be a classic.

Mullen's Hugo-nominated tale, Space to Swing a Cat (Astounding, June 1958) is also worth a read. In this story, animals have been mutated to express intelligence, so they can act as pilots in space. The improved reflexes and single-mindedness of different species are explored (dogs are too stupid, lions too lazy), and it's found that tigers are the best. It's not up to the standards of Fool Killer, but it's not bad. His novel probably isn't worth investigating, however, as it received very poor reviews from the likes of Damon Knight and James Blish upon publication.

NEW FEATURE 8 September 2021

Dangerous Visions - Ed. Harlan Ellison

Published in 1967, the SF anthology Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison, has legendary status in the genre as being probably the finest and most influential anthology of new SF stories ever produced. It set a very high standard, several its stories won major awards and the author list read like a who's-who of 20th-century SF.

I recently acquired a near-mint condition first edition of the book (see photo) and have enjoyed reading through it. Ellison wrote interesting and generally quite edgy introductions to each story, which also featured afterwords by each author. My review of each story in Dangerous Visions can be found as a new feature article here.

The finest stories were submitted, in my opinion, by Robert Silverberg (Flies), Philip K. Dick (Faith of Our Fathers), Larry Niven (The Jigsaw Man), Sonya Dorman (Go, Go, Go, Said the Bird), R. A. Lafferty (Land of the Great Horses) and Norman Spinrad (Carcinoma Angels).

REVIEW 22 August 2021

The Hemingway Hoax - Joe Haldeman

Haldeman's short novel or novella, The Hemingway Hoax (1990) won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards for Best Novella, and it certainly confirms Haldeman as being one of the finest and most literary SF writers of the modern era. Haldeman draws on both his love of Hemingway's work, and his own awful experiences from the Vietnam war, to provide a rich, interesting and entertaining story. In 1922, Hemingway's first wife Hadley famously lost most of his unpublished fiction on a train at Paris Gare de Lyon station. This tragic episode set Hemingway back in his writing, and was chronicled in his autobiographical book, A Moveable Feast, which covered his early writing life in Paris, as part of the 'Lost Generation'. As it happens, I read A Moveable Feast immediately before I read Haldeman's work, which set me up beautifully to enjoy this book. I'd recommend reading them like this, if like me you're a Hemingway fan. (A Moveable Feast is itself wonderful, by the way, as George R. R. Martin recently reminded us on his Not a Blog website).

Haldeman's tale considers whether someone could write a pastiche of some of Hemingway's lost fiction. A Boston university professor decides to see if it is indeed possible to produce a hoax manuscript, which in theory could net millions of dollars. However, as soon as he begins the project, he is visited by a mysterious figure, who takes the guise of Hemingway himself, and who tells him he should not continue with the venture. Hemingway's works are clearly important to the stability of the multiverse; universe-hopping and time travel provide speculative elements, and these are dealt with expertly by Haldeman and whole is neatly drawn.

Haldeman is clearly a bit of a Hemingway scholar, and he says he's been interested in Hemingway's work and life for 25 years; in his afterword, he notes that, like the central protagonist of the story, he also was a Boston literary professor, and also vacationed at Key West. As a result, this short novel not only provides a lot of fun for Hemingway and SF fans, but adds detail to one's understanding and knowledge of the great writer. All-in-all, a super short read, that's highly recommended.

SHORT REVIEW 15 August 2021

Into the Storm - Taylor Anderson

Into the Storm is the first in Taylor Anderson's ongoing alternate history Destroyermen series. The concept is that an old and ill-equipped WWI-era destroyer called into action in WWII encounters a Japanese fleet of ships in Asiatic waters, and looks doomed, until it passes into a strange squall, which transports the ship and everyone on it to a parallel Earth. This is a very different Earth, in which dinosaurs did not die out, and humans do not appear to exist. The sentient species of the the planet appear to be an aggressive descendent of velociraptors, and a lemur-like mammalian species, which are at war with each other.

The book starts at a cracking pace, which Anderson handles well, maintaining intensity while also deftly providing interesting background on the old destroyer, USS Walker, and its crew. One of the joys of alternate history is that you learn as you're entertained; with Into the Storm, the old 'four-stacker' destroyers are interestingly brought to life. The invented elements here, such as the evolved sentient species are also well-thought out and make reasonable scientific sense.

This falls into the SF sub-genre of 'alternate history', as it's set in 1942, but it also reads like a cross between Harry Harrison's West of Eden, and The Land That Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Overall, it's a satisfying novel, though it does read as the first book in a longer series; the conclusion cannot wrap everything up, and much is left unresolved for subsequent books. There are now 15 books in the ongoing series and whether I ever read them all is far from certain, but the second book, Crusade, has at least joined my to-be-read list. These books should certainly be read in order, judging by Into the Storm, so if this sounds of interest, be sure to begin with this first book.

NEW FEATURE 19 July 2021

FoundationSeries Publication History

The Foundation series of books, by Isaac Asimov, of course started life as individual short stories and novellas, published over an 8 year span in Astounding magazine. This pictorial feature outlines the publication history of the popular series from 1941 until the present day, showing which editions contain which books. For collectors of either the original Astounding magazine issues containing the stories, or of particular paperback editions, this feature may be of some use, as well being an interesting diversion for fans of the Good Doctor's most famous work. Click here for the feature article.

SHORT REVIEW 1 July 2021

Children of Time - Adrian Tchaikovsky

Children of Time is a modern SF novel (2015) which has garnered very positive reviews, averaging a whopping rating of 4.27 out of 5.00 on goodreads at the time of writing. Tchaikovsky has come up with some great ideas here and it's these quite novel SF concepts that have led to the general appreciation, I suspect. In the future, advanced stellar ships set out from Earth to terraform and seed other planets. The 'seeding' was to take place using monkeys, coupled with a 'nanovirus' that would speed up their evolution. Unfortunately the seeding expedition succumbed to terrorism at the critical juncture. Jumping forward thousands of years, humankind has essentially ruined the Earth, and the few survivors of the human race, in cold-sleep aboard a slow ark ship, arrive at the same planet to find that all is not well. The principle species to have been influence by the nanovirus on the terraformed planet are actually giant spiders. So, regarding ideas - especially the idea of huge amounts of time passing for the arc crew between the occasions they wake up - it is interesting, and the novel starts brightly and engagingly. Unfortunately, it gets slower and less engaging as it progresses. The book alternates between chapters concerning the human crew of the ark ship, and chapters concerning the spiders on the planet. The humans are not appealing, and the spiders are not consistently interesting. As such long passages of time occur between sections of the book, the same individual spiders are not present from one section to another. Tchaikovsky gets around this problem by giving spiders from different eras the same name, to try and deliver some continuity, but for me it doesn't really work. The book also spends far too long bringing the two races together, so that the alternating chapters are almost completely unconnected for hundreds of pages. This is a long book (600 pages), and frankly it became a slog to keep going. It took far too long for any payoff to occur, and the way the characters were drawn, I found I couldn't care what the conclusion was going to be, anyway. I got close to 400 pages through the novel, but couldn't actually bring myself to finish it, which tells you all you need to know, I think. My recommendation: give it a miss, there are better SF books out there.

SHORT REVIEW 22 May 2021

Camouflage - Joe Haldeman

Joe Haldeman is an accomplished author, having obtained a Masters degree in Creative Writing from the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. He was made a SFWA Grand Master in 2009, and was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2012. His first novel, The Forever War, won both the Hugo Award and Nebula Award for best novel. His books, exemplified by The Forever War, often reflect his experiences as a veteran of the Vietnam war. A popular figure among his SF writing peers, Haldeman's work is worthwhile and enjoyable.

Camouflage is no exception - this highly engaging and exciting book won the Nebula Award in 2006. The novel is written with great pace and deals with one of the most popular tropes in SF: aliens among us. An artifact is found on the ocean floor at incredible depth, buried under a million-year-old coral formation. Once the spaceship-like artifact is brought up and beached in Samoa, researchers find it has an unearthly density, resilience and origin. What the researchers don't know is that the artifact came from another star, and brought an alien with it - a changeling that has been living on Earth for a million years, existing in the guise of many different species. Now it's finally taken human form and is attracted to the artifact.

To make things more complex, the alien is not alone. A second, and more mysterious alien of unknown origin - a chameleon - is also stalking the Earth, full of evil intent, killing for pleasure whenever it can. The story is told in an open, clear manner, making it easy to follow. The 'changeling' and 'chameleon' abilities of the two aliens are used as plot devices throughout in a satisfying and clever way, and the conclusion is quite strong. This novel is highly recommended, and would be a good book to recommend to new readers who wish to dip their toes in the SF literary waters. One can't help noticing that many other authors might have wrought a long novel series from the idea, but Haldeman has shown a restraint I appreciate, writing a solid novel that stands alone and doesn't require a sequel.

SHORT REVIEW 26 April 2021

Alone Against Tomorrow - Harlan Ellison

This 1971 collection of Harlan Ellison short stories carries the subtitle Stories of Alienation in Speculative Fiction, and collects previously published SFF stories on the themes of alienation, isolation and loneliness. While it is not a 'best of' collection, a lot of Ellison's best work dealt in these themes, so the collection is a good one, gathering many of his famous works published prior to the end of the 1960's. Among the most famous stories are I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream (1967) and "Repent, Harlequin!" Said the Ticktockman (1965). The former of these is a very well known SF story, providing genuine horror - and if you've not read it, seek it out (it's widely available in many SF short story anthologies). The latter is more whimsical and jokey, but is highly effective. Both these stories won the Hugo Award and "Repent..." won the Nebula as well.

The other stories in the collection span from 1956 through to 1969. It might be assumed that the more well known stories from the mid-late '60's would be the finer work here, but in fact some of the older stories are very effective. As a tale of isolation and the loneliness of deep space the tale Night Vigil (1957) is successful and enjoyable. Likewise, The Discarded (1959) and Are You Listening? (1958) worked well for me.

Overall, this is a pretty strong collection. It is out-of-print currently (and not likely to be reprinted) but is widely available from used book sellers and easy to find on sites such as eBay. Fans of SF should read Ellison fairly often, perhaps, as you're reminded when doing so how inventive and striking SF short stories can be. Ellison doesn't always hit a home run, and in any collection there will be stories that don't satisfy, but his batting average is pretty good, and when he's good, he's very good. Recommended.

SHORT SERIES REVIEW 24 April 2021

Riverworld Novels - Philip José Farmer

I first read the Riverworld series, by Philip José Farmer in about 1986. It left a mark on me as a super piece of SF and I'd long looked forward to re-reading it. The concept Farmer presents is that everyone who has ever lived on Earth wakes, thousands of years after their deaths, all at the same time on the banks of a great river that crisscrosses an entire world. Nearly 20 million miles long, the river is now home to 36 billion people from all times on Earth, going back to the stone age.

The second novel, The Fabulous Riverboat, does not include Burton much, but switches focus to Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) and his reluctant ally King John, in their attempts to build a great riverboat from a fallen asteroid. Twain has, like Burton, been approached by a renegade 'Ethical' who wishes certain select resurrectees to travel to the headwaters of the river in the arctic circle to reach the stronghold of the Ethicals. Twain, wishing answers, and also wishing to become a riverboat captain again, agrees to the challenge. The story of Twain building his boat, and his tussles with King John are very readable, but it is a shame the book does not link up with Burton more and bring the two story threads together further. A lot of the book's charm comes from the background information on Mark Twain.

The first book, To Your Scattered Bodies Go, is the best in the series. Each book follows different characters, with some intermixing of their storylines, and the first novel concentrates on the the Riverworld life of several well-known figures from history: Sir Richard Burton (the Victorian explorer and linguist), Alice Liddell (The real-life inspiration for Alice in Wonderland) and Herman Goering. Winning the Hugo Award for best novel in 1972, its an absolute cracker of a book. Part of the enjoyment comes from the background that is supplied on the historical figures, which is presented in an interesting and thoughtful way. This first novel describes Burton's attempts to understand how and why humankind has been resurrected, and he learns a fair bit about the 'Ethicals' who have engineered the world over the course of the book.

The third book, The Dark Design, is fatter and slower. While Twain is back, he's a minor character, and Burton does not appear at all. The main characters are imagined persons, rather than historical figures, and the plot is starting to go over much of the same ground covered previously. In this book, a dirigible is being built to reach the Ethicals at the pole faster than Twain's boat, and it seemed a mistake on Farmer's part to enable this solution to the problem of how to get there. While historical figures do appear (Tom Mix and Jack London, notably), they are not fleshed out as well as Burton and Twain in the previous books. In many ways this book is not nearly so successful, and the aims of previous book protagonists to solve the riddle of the Riverworld are not advanced, despite the greater length of this book. The fourth book, The Magic Labyrinth, answers the questions regards the Ethicals and the purpose of their resurrection experiment, but I have not yet read it in this re-read. So, how does the series rate, and what books are recommended? Certainly the first book is recommended, and it actually stands alone fairly well. The second is also a pacey and fun read, and while it will not answer all the queries one would have about the Riverworld, and ends in a rather abrupt and sudden manner, it is worth a read to continue after book 1. Just be warned, if you like Burton, he's not in it much - but if you love Mark Twain, its enjoyable to read a story featuring him. Reading further than this is not necessarily recommended. The third book is weaker, and doesn't advance the series story much. However, the fourth is - if memory serves - a little better and does provide some resolution to the series, so if you're really into the series, you'll want to read book 3 simply to get to book 4. A fifth book, The Gods of Riverworld, was a late add-on, and is not I believe essential reading.

SHORT AUTHOR PROFILE & STORY REVIEW 6 April 2021

Jack McDevitt & Voice in the Dark

I recently undertook an interesting reading exercise, in which I read through all the Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine issues from 1986. For the purpose of the exploration, I assigned each story in the issues with a 'reputation score', with marks given for awards won, award nominations, subsequent inclusion in anthologies, etc. I then read the top 3 reputation score stories from each issue. This feature article can be found under the magazine tab above, or click here. The reason I mention this, is that the finest story I read in these old magazines did not obtain a high 'reputation score', though it was excellent and recommended reading. The story was the novella Voice in the Dark, by Jack McDevitt. This novella is an extract from his 1986 first novel The Hercules Text, which I have not yet read. In the tale, a signal from a distant pulsar suddenly stops, and then returns, but with gaps that fit mathematical sequences, providing proof of extraterrestrial intelligence. When the messages become more complex, information is transmitted that could threaten our survival, given humankinds proclivity to self-destruct. What should those who received the information do with it? The story explores whether all information should be shared, and whether we are capable of surviving increasing technological advances as a race. The implications of the story are profound and frightening. This is a very, very good SF novella - one of the best I've read, and will join the short list of stories I advise new readers seek out. It wasn't even nominated for either the Hugo or Nebula Awards, but it deserved to have won both. So, if you're looking for a great hard SF novella to read, look out for Voice in the Dark.

Jack McDevitt (born 1935) is a very good SF writer, though not someone I've featured on the site before. He writes in a smooth and accessible manner, while maintaining smart plots and thoughtful ideas. He is perhaps most famous for two ongoing series of books, that feature returning characters - the Alex Benedict series and the Priscilla Hutchins series. While they cross-reference events in other books in the same series, books from these series all standalone well. His signature plot device is the discovery of alien artifacts, and first contact - themes he has written about in numerous quality novels. I have read several of McDevitt's books, from the two series mentioned, and also a few of his non-series SF novels.

Books by McDevitt that I've particularly enjoyed include:

Eternity Road (1998) - Far future Earth novel in which survivors explore an Earthly wasteland

Infinity Beach (2000) - great far future first-contact novel

A Talent for War (1989) - First Alex Benedict novel - alien archeology

Polaris (2004) - Second Alex Benedict novel - more alien archeology and mystery

The Engines of God (1994) - First Priscilla Hutchins novel - contains very big SF ideas

While I mentioned the novella Voice in the Dark did not win any awards, McDevitt did win the Nebula Award for Seeker, the third Alex Benedict novel, and eleven of his other SF novels have been nominated for Nebula Awards.

NEW FEATURE ARTICLE 13 March 2021

Astounding/Analog Authors Through the Decades

Ever wondered which authors have had the most stories published in the most famous and historically-important SF magazine, Astounding Science Fiction (later renamed to its current title Analog Science Fiction & Fact)? By collating author data for each decade, I have arrived at some interesting statistics. The article can be found via the features link above (or click here).

The top ranking 15 or so authors for each half-decade are listed (see '30-'34 table shown here as an example), along with a final top 10 for each full decade. At the end of the feature article, summary statistics for all time are presented.

One of the nice things about the undertaking of collating every author's input to the magazine, from every issue, has been learning more about some of the classic and well-represented authors, especially from the early years. I have a new-found respect and knowledge of the likes of Nat Schachner, Raymond Z. Gallun and others as a result. It was interesting, in researching the early magazines from before the 'Golden Age', to learn about F. Orlin Tremaine's 'thought variant' story initiative that ran from December 1933 to mid-1937. These 'thought-variants' are discussed and described in another article under the 'magazine' link above, for those who are interested.

SHORT REVIEW 28 February 2021

Slan - A. E. van Vogt

Slan was a hugely popular and well-regarding novel in the 1940's. Originally serialised in Astounding Science Fiction (Sep-Dec 1940) it was first published as a novel in 1946. The story concerns the racial enmity and fight for supremacy between 'normal' humans and a race of super-human, named 'slans', after their originator Samuel Lann. In this future, the world is run by the original human race, under a dictator, who runs an autocratic 'antislan' world government. One young slan, Jommy Cross, escapes detection and destruction by the humans and, with the aid of secret technology developed by his late slan father, tries to protect and and improve the position of slans in the world. Like most van Vogt books, Slan is a frenetically-paced book, full of action and ideas. This very pace doubtless helps the reader from inquiring too deeply how well it all fits together. No sooner do you read through a highly fortuitous and previously unsignaled plot device or some hand-waving technological description and start to think, "Hey, now, wait a minute..." than van Vogt sweeps you off again with the next improbable development and you kinda forget the issue you had. At the end of the day, van Vogt is about cramming multiple science-fiction ideas into fast-paced adventures, and Slan delivers on that front.

REVIEW 11 February 2021

Timescape - Gregory Benford

Timescape, by Gregory Benford (1980) won the Nebula Award, the British Science Fiction Award, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. It's a magnificent achievement and thoroughly recommended, not only for lovers of SF, but also for those who are thinking of trying out the genre. Benford is an astrophysicist and Professor Emeritus at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Irvine. As a significant and accomplished physical scientist in his own right, he was able to create not only an intelligent hard-SF novel that makes good internal sense, but also the best novel about science that I have ever read. As a scientist myself, I'm well aware how wrongly it is often portrayed in books and film. The scientific process, the need to publish in scientific journals, the inter-relationships between scientists, and the uncertainties behind scientific theory are all captured perfectly.

This is a time-travel story; but the difference here is that the time travel is conducted only through messages, sent from 1998 back to 1963 by way of tachyon transmissions. The attempt is being made, from Cambridge in the UK, as the world in '98 is suffering an ecological disaster. If only a message can be sent back to '63 to warn scientists then of the impending disaster, perhaps they could amend their experiments on crop optimisation - experiments that ran out of control. The method of messaging is very clever, and the dual perspective - half told from Cambridge and half from the receiving laboratory in La Jolla in 1963 - works very well. The storyline in La Jolla chiefly concerns the interpretation of the nuclear resonance 'messages' detected in a lab sample of indium antinomide and reads like a detective story. The '98-based scenes in the UK offer a counterpoint to this storyline, by providing pathos and urgency.

Overall, this may be the finest hard science-fiction story I've read. Gregory Benford is not the household name in the genre he perhaps should be. This novel alone would make him a worthy recipient of the SF Grand Master award.

REVIEW 18 January 2021

Destiny Doll - Clifford D. Simak

Destiny Doll is, one the one hand, quite unlike much of Simak's output, and on the other, still very recognisably 'Simakian'. If you wanted an example novel to go along with a definition of what is science-fantasy (rather than straight SF), here it is: Destiny Doll. A young, rich woman hunter of alien big game (Sara) obtains the services of a cynical starship captain (Mike), who is himself on the run from his misdeeds, to seek out a fabled adventurer (Lawrence Knight) who left known space many years ago in search of something. Sara and Mike are guided across the galaxy by a blind telepath, George, who hears a voice telling him where to go, and George's helper, an apparently weak and possibly fraudulent religious man, 'Friar Tuck'. Upon reaching the planet of their destination, they find they are held captive by the planet, and undertake a quest across its surface in search of Knight. On the face of it this sounds like a fairly standard SF plot, until you encounter the characters and witness the scenarios that befall the troupe. Helped by a strange alien (Hoot), our heroes are at first waylaid and then helped by hobby horses (yes, that is indeed rocking horses), meet centaurs, a robot who speaks almost entirely in rhyme, and are attacked by trees. And ultimately the destiny of our heroes is deeply affected by an ancient wooden doll. To say more would enter spoiler territory, but the fantastical elements here are clearly stronger than the SF elements. But as strange as all this is, Destiny Doll is a compelling read, and internally consistent. Reading like a cross between The Wizard of Oz and Through the Looking Glass, Simak uses his full imagination here to weave an intriguing plot, and inquire: what is it we are searching for and why? Is it a place, a thing or a feeling, and can our greatest desires fulfill us if they are isolated wishes, rather than being part of a social or group destiny? The allegories here give this book a depth and thoughtfulness that raises it above many SFF novels and Simak's prose is clean and clear as usual. Moreover, we are aided in accepting the utter strangeness of the planet by the cynical captain, who finds it all quite as strange as us and looks on it as a bizarre place he wants to escape. Also noteworthy is the fact that Simak's captain Mike Ross is a cynical no-good (at least at the start) which is unusual for Simak, but it allows the character to be the be both the foil to our disbelief in the planet and also provides Simak a flawed character who can ultimately find redemption. So, this novel is recommended - suspend your SF disbelief and enjoy the ride.

REVIEW 10 January 2021

Fire with Fire - Charles E. Gannon

Baen book covers are all bright, with high colour, jazzy type and suggest old-fashioned, rip-roaring SF with a military bent. This doubtless works well for them in sales, but to have such a singular publication style does seem to throw all the books into one basket. A casual reader could be excused for thinking they are all rather similar, pulpy and/or low-brow. Thankfully, Baen books are much more varied than this, and this book by Charles E. Gannon is a great example of "don't judge a book by it's cover". Fire with Fire (2013) is an intelligently written novel of first contact and alien world exploration, but also a tightly plotted thriller. Reading like a cross between a fast-paced Robert Ludlum novel and one of Jack McDevitt's ancient alien discovery books, this is a superior SF novel. It was nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel, and quite rightly so. Gannon combines a sharp intellect with well-researched science and political machinations that ring true. His characterisation is also good, with the protagonist, Riorden Caine, proving to be a likeable hero.

This is a good sized novel (about 650 pages) but it reads quickly and is well written. One of Gannon's strengths throughout the book is the suggestion that there is more to come, and bigger things to be discovered and revealed, without ever giving the game away. His aliens, as we see more and more of them, are also interesting and well conceived, reminding me of the deft touch Cherryh always has with aliens. The only downside for some (it will be an upside for many) is that while the book is complete, it is clearly the first in a longer series. If you want a book that is entirely standalone, this may not be for you - it's clearly leading into a greater confrontation between humans and the other alien races. There are four sequels: Trial by Fire (2014), Raising Caine (2015), Caine's mutiny (2017), and Marque of Caine (2019).

The fact that 4 of the 5 novels in the Caine series have been nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel should demonstrate these are more than just pulpy fast reads. Incidentally, Gannon would appear to be a smart cookie: a Distinguished Professor of English, Fulbright Fellow and expert consultant for national media (e.g. Discovery Channel) and intelligence and defense agencies, including The Pentagon, Air Force, NATO and NASA.

For earlier years' articles hit the relevant archive button below

2021 Article Archive 2020 Article Archive